Contents

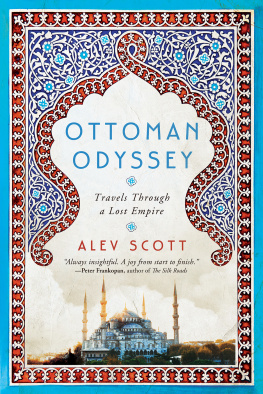

ALSO BY ALEV SCOTT

Turkish Awakening

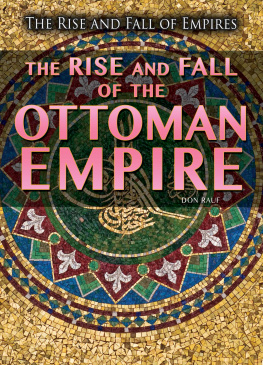

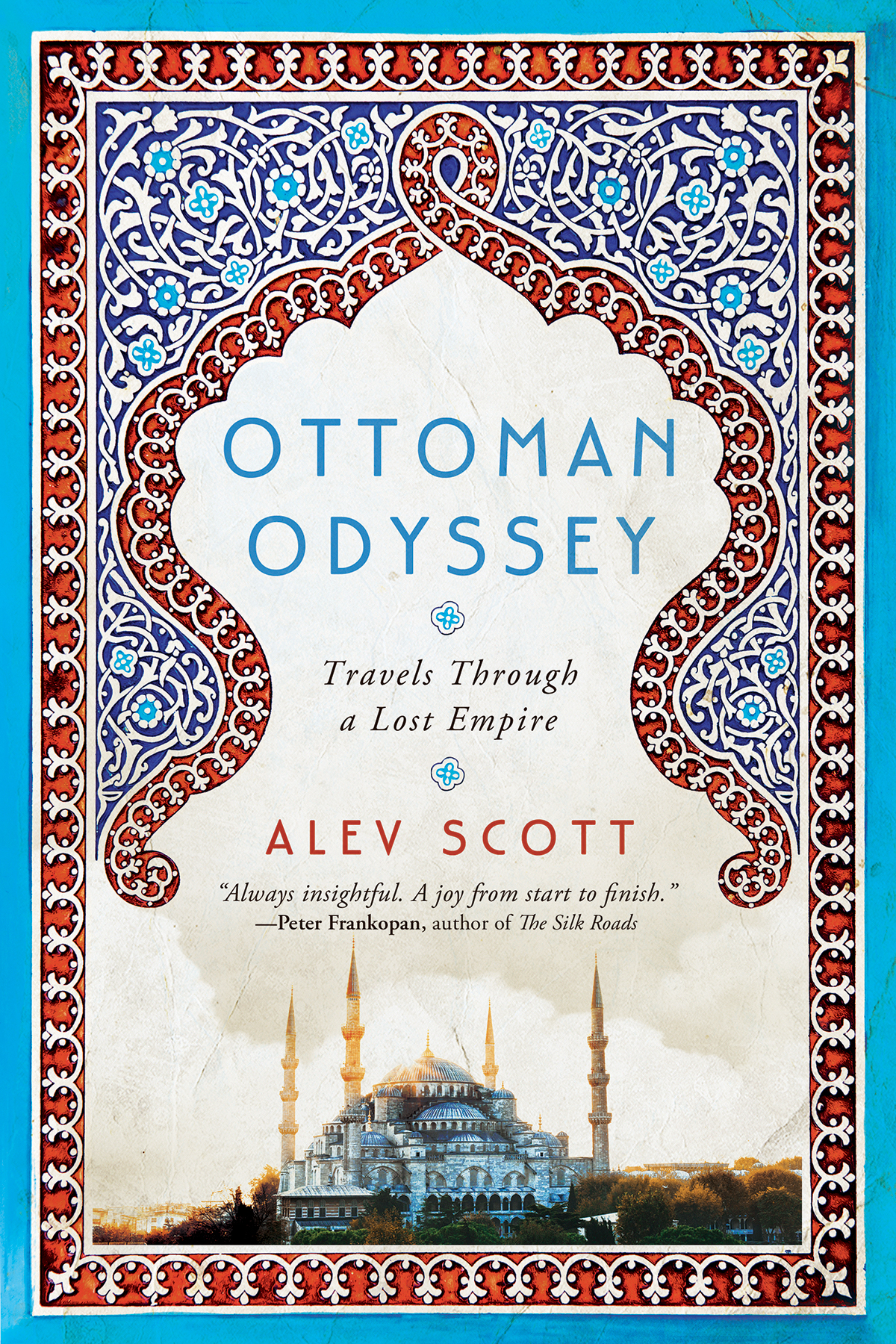

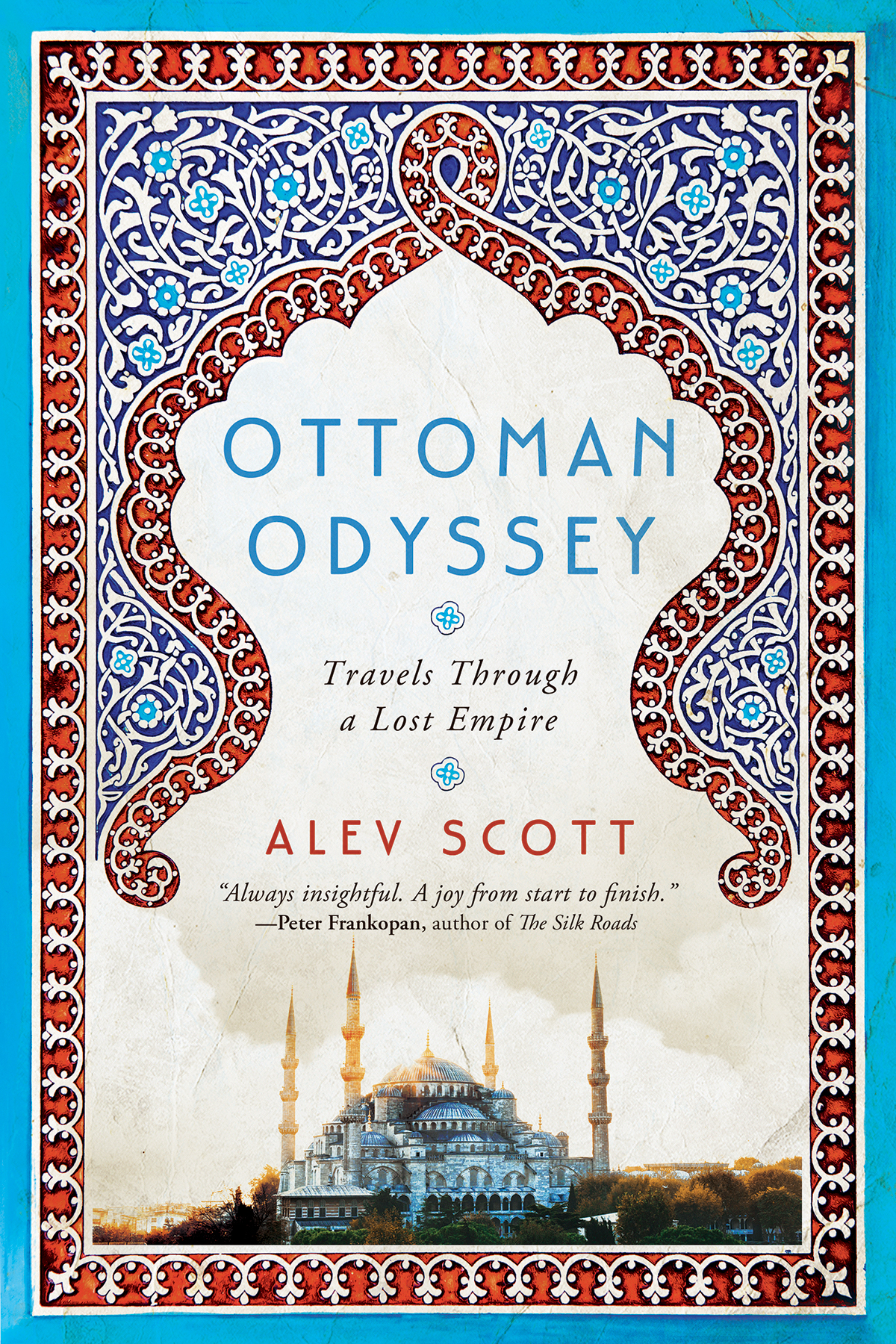

OTTOMAN

ODYSSEY

Travels Through a Lost Empire

ALEV SCOTT

PEGASUS BOOKS

NEW YORK LONDON

OTTOMAN ODYSSEY

Pegasus Books Ltd.

148 West 37th Street, 13th Floor

New York, NY 10018

Copyright 2019 by Alev Scott

First Pegasus Books hardcover edition May 2019

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced

in whole or in part without written permission from the publisher,

except by reviewers who may quote brief excerpts in connection with a review

in a newspaper, magazine, or electronic publication; nor may any part of this

book be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or

by any means electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or

other, without written permission from the publisher.

ISBN: 978-1-64313-075-0

Distributed by W. W. Norton & Company, Inc.

In memory of my Granny ifa,

and other victims of nationalism.

In the capital of Turkey, in a palace with a thousand rooms, a man sits on a gilt throne. Some of his soldiers are ornamental and armed with sabres, others fly F-16s and protect him from military coups. The year is 2018. The man is President Erdoan. The fantasy is Ottoman.

The Republic of Turkey emerged in 1923 from the ashes of the Ottoman Empire, which at its zenith stretched from Mecca to Budapest, from Algiers to Tbilisi, from Baghdad to the Crimea, connecting millions of people of different religions and ethnicities. An Ottoman subject was an Eastern Orthodox Christian from Odessa or a Jew from Mosul, a Sunni Muslim from Jerusalem or a Catholic Syriac from Antakya. The sultan, who was also the caliph, leader of the Islamic world, allowed non-Muslims to organize their own law courts, schools and places of worship in return for paying infidel taxes and accepting a role as second-class citizens: a system of exploitative tolerance that allowed diversity to flourish for centuries in the greatest empire of early modern history.

In recent years, a bizarre reinvention has been taking place in Turkey: its politicians are reclaiming the legacy of its Ottoman past, while the country remains as nationalistic as ever. In 2017, the country voted to grant unlimited powers to President Erdoan, nearly a century after the abolition of the Ottoman Sultanate. For some, this was an unfathomable act of political suicide, an event that marked the end of democracy in Turkey. For others, it was a reharnessing of the strength the country needs to lead the Middle East by shining example and stand up to Europe: a return to the kind of power exemplified by the Ottoman Empire.

The last century [the period of the Republic] was only a parenthesis for us. We will close that parenthesis. We will do so without going to war, or calling anyone an enemy, without being disrespectful to any border, we will again tie Sarajevo to Damascus, Benghazi to Erzurum to Batumi. This is the core of our power. These may look like different countries to you, but Yemen and Skopje were part of the same country a hundred and ten years ago, as were Erzurum and Benghazi.

The words of Ahmet Davutoglu, Foreign Minister in 2013, sold Turkish voters a heady if vague pride in a long-fallen empire, and a belief that it could be effortlessly resurrected. In fact, the discrepancies between the Ottoman glory days and the reality of modern-day Turkey are stark, but Erdoan and his Justice and Development Party have been adept at claiming the best of the empire and ignoring the worst of it. On 8 February 2018, the which provided Turkish citizens with access to their family trees via digitalized census and tax records stored in the state archives of Istanbul. These archives stretch back to the 1830s, recording the births and deaths of Ottoman subjects scattered across the empire. Within hours, millions had rushed to the e-devlet (e-government) portal in an orgy of self-discovery; the website promptly crashed.

Bulent etin was one of the lucky ones who managed to access the site to download his family tree in the first couple of hours. He found that most of his mothers side of the family were born outside the borders of modern Turkey, in what was previously Ottoman territory: his great-great-grandfather in Macedonia in 1869, his great-great-grandmother in the Caucasus in 1864. Somehow, they produced Bulents great-grandfather in Sivas, in central Anatolia, in 1897, and subsequent generations remained within Turkey, resulting in the birth of Bulent himself in the Republics capital of Ankara in 1986. Like many Turkish citizens, Bulent sees no contradiction in being a patriot who is also proud of his Ottoman ancestry, telling me he feels Turkish because we are all united under this flag, within this country, sharing the same destiny.

When the website relaunched six days after its crash to a renewed wave of interest, there were unforeseen consequences: Turks who discovered ancestors from ex-Ottoman territories now in the European Union Bulgaria and Greece, most commonly started making applications for second citizenships bleak; they would rather use their Ottoman heritage to escape the backward-looking Turkey of today.

While right-wing politicians in Europe, the US and Turkey have misleadingly evoked the glory of vanished empires to harness nationalist votes in recent years, the Left are also guilty of nostalgia, of looking through rose-tinted spectacles at a particular version of the past. In the case of the Ottoman Empire, the diversity of its subjects is sometimes presented as proof that everyone lived in a constant state of peaceful coexistence. This is not true; non-Muslims were second-class citizens, and at the turn of the 20th century there were horrific systematic abuses of these subjects as the empire began to eat itself. Yet the fact remains that its 600-year-old social diversity is almost impossible to imagine today in countries like Turkey, a country that suppresses difference even in thought.

Halfway through my research for this book I was barred from Turkey, which drastically changed both my life and the course of the book.

I had first decided to write about the social legacy of the Ottoman Empire while I was in south-east Turkey in 2014, near the Syrian and Iraqi borders. Unlike most of Turkey, where signs of its former wealth of peoples, cultures and religions have been systematically eroded over the past century, towns like Mardin and Antakya offered a glimpse of the Ottoman world I was trying to reimagine at least, a Levantine corner of it. But by 2015, al-Qaeda and IS had crossed the Syrian border and established cells in these towns. The risk of kidnap for Western journalists was high; even veteran war reporters avoided the area, and suddenly the gentle historical field trips Id planned seemed a little nave. Still, I had most of Turkey open to me, and its neighbouring countries, to continue my research. Then, in 2017, while travelling in Greece, I failed to get permission to cross over the land border back into Turkey, and discovered I had an entry ban on my passport, placed by the Interior Ministry. The ministry staff offered no explanation for this, but I knew it was my political journalism, and my appeals were ignored.

That is how this book became an odyssey encompassing eleven countries of the former Empire. I found myself speaking Turkish with car mechanics in rural Kosovo and with the children of Armenian genocide survivors in Jerusalem; I discussed Ottoman religious diversity with Lebanese warlords and professors in Turkish universities in Sarajevo. My entry ban motivated me to go out and explore the ways in which the empire shaped the histories of people in the Balkans, the Caucasus and the Levant. I found myself asking questions about forced migration, genocide, exile, diaspora, collective memory and identity, not just about religious coexistence.