Thank you for purchasing this Simon & Schuster eBook.

Join our mailing list and get updates on new releases, deals, bonus content and other great books from Simon & Schuster.

C LICK H ERE T O S IGN U P

or visit us online to sign up at

eBookNews.SimonandSchuster.com

CONTENTS

No Ordinary Time has won the following awards:

Pulitzer Prize for History

Harold Washington Literary Award

New England Bookseller Association Award

The Ambassador Book Award

The Washington Monthly Political Book Award

T O MY SONS,

R ICHARD, M ICHAEL, AND J OSEPH

PREFACE

On May 10, 1940, Hitler invaded Holland, Luxembourg, Belgium, and France, bringing the phony war to an end, and initiating a series of events which led, almost inevitably, to Americas involvement in historys greatest armed conflict. The titanic battles of that war, the movement of armies across half the surface of the globe, have been abundantly described. Less understood is how the American home front affected the course of the war, and how the war, in turn, altered the face of American life. This book is the story of that home front, told through the lives of Franklin and Eleanor Roosevelt and the circle of friends and associates who lived with them in the family quarters of the White House during World War II.

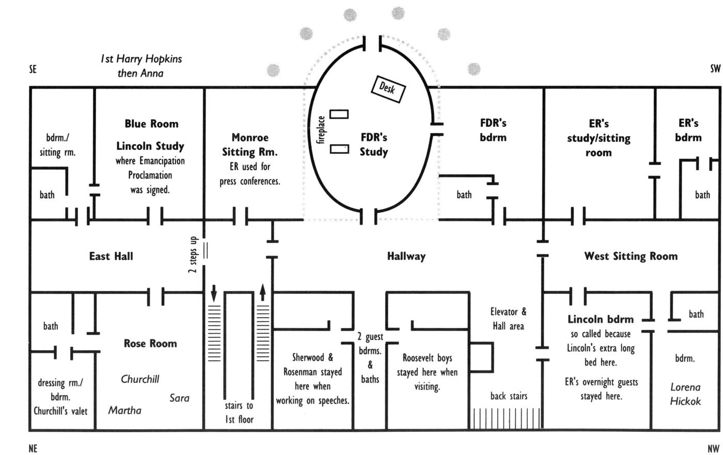

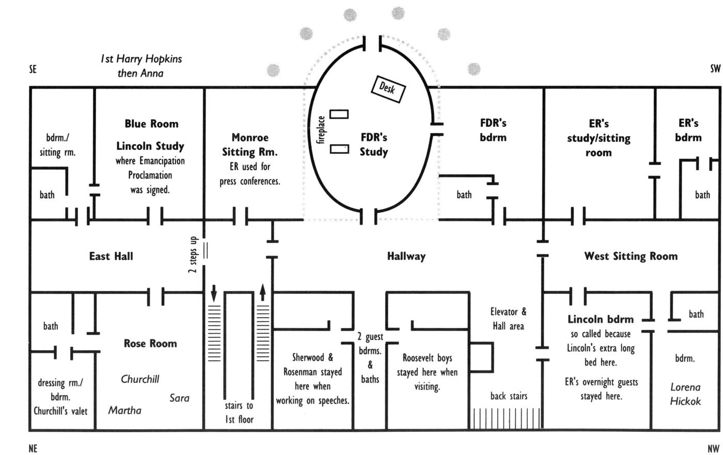

The Roosevelt White House during the war resembled a small, intimate hotel. The residential floors of the mansion were occupied by a series of houseguests, some of whom stayed for years. The permanent guests occasionally had private visitors of their own for cocktails or for meals, but for the most part their lives revolved around the president and first lady, who occupied adjoining suites in the southwest quarter of the second floor. On the third floor, in a cheerful room with slanted ceilings, lived Missy LeHand, the presidents personal secretary and longtime friend. The presidents alter ego, Harry Hopkins, occupied the Lincoln Suite, two doors away from the presidents suite. Anna Boettiger, the presidents daughter, moved into Hopkins suite when Hopkins moved out. Lorena Hickok, Eleanors great friend, occupied a corner room across from Eleanors bedroom. This group of houseguests was continually augmented by a stream of visitorsWinston Churchill, who often stayed for two or three weeks at a time; the presidents mother, Sara Delano Roosevelt; Eleanors young friend Joe Lash; and Crown Princess Martha of Norway.

These unusual living arrangements reflected the presidents need to have people around him constantly, friends and associates with whom he could work, relax, and conduct much of the nations business. Through these continual houseguests, Roosevelt defied the limitations of his paralysis. If he could not go out into the world, the world could come to him. The extended White House family also permitted Franklin and Eleanor to heal, or at least conceal, the incompletions of their marriage, which had been irrevocably altered by Eleanors discovery of Franklins affair with Lucy Mercer in 1918. There were areas of estrangement, untended needs that only others could fill.

Encompassed by this small society, Franklin Roosevelt led his nation through the war. Although his role as commander-in-chief has been studied at length, less attention has been paid to the way he led his people at home. Yet his leadership of the home front was the essential condition of military victory. Through four years of war, despite strikes and riots, overcrowding and confusion, profiteering, black markets, prejudice, and racism, he kept the American people united in a single cause. There were indeed many times, as those who worked with him observed, when it seemed that he could truly see it allthe relationship of the home front to the war front; of the factories to the soldiers; of speeches to morale; of the government to the people; of war aims to the shape of the peace to come. To understand Roosevelt and his leadership is to understand the nation whose strengths and weaknesses he mirrored and magnified.

At a time when her husband was preoccupied with winning the war, Eleanor Roosevelt insisted that the struggle would not be worth winning if the old order of things prevailed. Unless democracy were renewed at home, she repeatedly said, there was little merit in fighting for democracy abroad. To be sure, she did not act single-handedlycivil-rights leaders, labor leaders, and liberal spokesmen provided critical leverage in the search for social justicebut, without her consistent voice at the upper levels of decision, the tendency to put first things first, to focus on winning the war before exerting effort on anything else, might well have prevailed. She shattered the ceremonial mold in which the role of the first lady had traditionally been fashioned, and reshaped it around her own skills and commitments to social reform. She was the first presidents wife to holdand losea government job, the first to testify before a congressional committee, the first to hold press conferences, to speak before a national party convention, to write a syndicated column, to be a radio commentator, to earn money as a lecturer. She was able to use the office of first lady on behalf of causes she believed in rather than letting it use her, and in so doing she became, in the words of columnist Raymond Clapper, the most influential woman of her time.

The two storiesthat of the Roosevelts and that of Americaare woven, in this book, as in reality, into a single narrative, beginning in May 1940 and ending in December 1945. This has required the tools of both history and biography: the effort to illuminate the qualities of Franklin and Eleanor Roosevelt has demanded occasional departures from chronology. Yet the spine of this work is narrative. Most studies of the home front have been arranged topicallyproduction, civil rights, rationing, women, Japanese Americans, etc. But a president does not deal with issues topically. He deals with events and problems as they arise. By following the sequence of events ourselves, it is easier to see the connections between the home front and the war, between the level of production at a particular time and the decisions about where and when to fight, between the private qualities of leadership and the public acts.

And there is also a quality to this period which can only be conveyed through narrativethe sense of a cause successfully pursued through great difficulties, a theme common to America itself and to the family which guided it. This is no ordinary time, Eleanor Roosevelt told the Democratic Convention of 1940, and no time for weighing anything except what we can best do for the country as a whole. Guided by this conviction, the nation and its first family would move together through painful adversities toward undreamed-of achievements.

SECOND FLOOR FAMILY QUARTERS*

*Missy LeHands suite was located on the third floor.

CHAPT ER 1

THE DECISIVE HOUR HAS COME

O n nights filled with tension and concern, Franklin Roosevelt performed a ritual that helped him to fall asleep. He would close his eyes and imagine himself at Hyde Park as a boy, standing with his sled in the snow atop the steep hill that stretched from the south porch of his home to the wooded bluffs of the Hudson River far below. As he accelerated down the hill, he maneuvered each familiar curve with perfect skill until he reached the bottom, whereupon, pulling his sled behind him, he started slowly back up until he reached the top, where he would once more begin his descent. Again and again he replayed this remembered scene in his mind, obliterating his awareness of the shrunken legs inert beneath the sheets, undoing the knowledge that he would never climb a hill or even walk on his own power again. Thus liberating himself from his paralysis through an act of imaginative will, the president of the United States would fall asleep.

Next page