SIMON & SCHUSTER

Rockefeller Center

1230 Avenue of the Americas

New York, NY 10020

Copyright 2005 by Blithedale Productions, Inc.

All rights reserved,

including the right of reproduction

in whole or in part in any form.

S IMON & S CHUSTER and colophon are registered trademarks

of Simon & Schuster, Inc.

Maps 2005 Jeffrey L. Ward

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data has been applied for.

ISBN-10: 1-4165-4983-8

ISBN-13: 978-1-4165-4983-3

Visit us on the World Wide Web:

http://www.SimonSays.com

For Richard N. Goodwin,

my husband of thirty years

The conduct of the republican party in this nomination is a remarkable indication of small intellect, growing smaller. They pass overstatesmen and able men, and they take up a fourth rate lecturer, who cannot speak good grammar.

The New York Herald (May 19, 1860), commenting on Abraham Lincolns nomination for president at the Republican National Convention

Why, if the old Greeks had had this man, what trilogies of playswhat epicswould have been made out of him! How the rhapsodes would have recited him! How quickly that quaint tall form would have enterd into the region where men vitalize gods, and gods divinify men! But Lincoln, his times, his deathgreat as any, any agebelong altogether to our own.

Walt Whitman, Death of Abraham Lincoln, 1879

The greatness of Napoleon, Caesar or Washington is only moonlight by the sun of Lincoln. His example is universal and will last thousands of years. He was bigger than his countrybigger than all the Presidents togetherand as a great character he will live as long as the world lives.

Leo Tolstoy, The World, New York, 1909

MAPS AND DIAGRAMS

INTRODUCTION

I N 1876, the celebrated orator Frederick Douglass dedicated a monument in Washington, D.C., erected by black Americans to honor Abraham Lincoln. The former slave told his audience that there is little necessity on this occasion to speak at length and critically of this great and good man, and of his high mission in the world. That ground has been fully occupied. The whole field of fact and fancy has been gleaned and garnered. Any man can say things that are true of Abraham Lincoln, but no man can say anything that is new of Abraham Lincoln.

Speaking only eleven years after Lincolns death, Douglass was too close to assess the fascination that this plain and complex, shrewd and transparent, tender and iron-willed leader would hold for generations of Americans. In the nearly two hundred years since his birth, countless historians and writers have uncovered new documents, provided fresh insights, and developed an ever-deepening understanding of our sixteenth president.

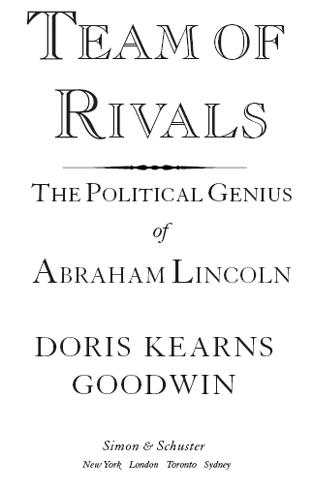

In my own effort to illuminate the character and career of Abraham Lincoln, I have coupled the account of his life with the stories of the remarkable men who were his rivals for the 1860 Republican presidential nominationNew York senator William H. Seward, Ohio governor Salmon P. Chase, and Missouris distinguished elder statesman Edward Bates.

Taken together, the lives of these four men give us a picture of the path taken by ambitious young men in the North who came of age in the early decades of the nineteenth century. All four studied law, became distinguished orators, entered politics, and opposed the spread of slavery. Their upward climb was one followed by many thousands who left the small towns of their birth to seek opportunity and adventure in the rapidly growing cities of a dynamic, expanding America.

Just as a hologram is created through the interference of light from separate sources, so the lives and impressions of those who companioned Lincoln give us a clearer and more dimensional picture of the president himself. Lincolns barren childhood, his lack of schooling, his relationships with male friends, his complicated marriage, the nature of his ambition, and his ruminations about death can be analyzed more clearly when he is placed side by side with his three contemporaries.

When Lincoln won the nomination, each of his celebrated rivals believed the wrong man had been chosen. Ralph Waldo Emerson recalled his first reception of the news that the comparatively unknown name of Lincoln had been selected: we heard the result coldly and sadly. It seemed too rash, on a purely local reputation, to build so grave a trust in such anxious times.

Lincoln seemed to have come from nowherea backwoods lawyer who had served one undistinguished term in the House of Representatives and had lost two consecutive contests for the U. S. Senate. Contemporaries and historians alike have attributed his surprising nomination to chancethe fact that he came from the battleground state of Illinois and stood in the center of his party. The comparative perspective suggests a different interpretation. When viewed against the failed efforts of his rivals, it is clear that Lincoln won the nomination because he was shrewdest and canniest of them all. More accustomed to relying upon himself to shape events, he took the greatest control of the process leading up to the nomination, displaying a fierce ambition, an exceptional political acumen, and a wide range of emotional strengths, forged in the crucible of personal hardship, that took his unsuspecting rivals by surprise.

That Lincoln, after winning the presidency, made the unprecedented decision to incorporate his eminent rivals into his political family, the cabinet, was evidence of a profound self-confidence and a first indication of what would prove to others a most unexpected greatness. Seward became secretary of state, Chase secretary of the treasury, and Bates attorney general. The remaining top posts Lincoln offered to three former Democrats whose stories also inhabit these pagesGideon Welles, Lincolns Neptune, was made secretary of the navy, Montgomery Blair became postmaster general, and Edwin M. Stanton, Lincolns Mars, eventually became secretary of war. Every member of this administration was better known, better educated, and more experienced in public life than Lincoln. Their presence in the cabinet might have threatened to eclipse the obscure prairie lawyer from Springfield.

It soon became clear, however, that Abraham Lincoln would emerge the undisputed captain of this most unusual cabinet, truly a team of rivals. The powerful competitors who had originally disdained Lincoln became colleagues who helped him steer the country through its darkest days. Seward was the first to appreciate Lincolns remarkable talents, quickly realizing the futility of his plan to relegate the president to a figurehead role. In the months that followed, Seward would become Lincolns closest friend and advisor in the administration. Though Bates initially viewed Lincoln as a well-meaning but incompetent administrator, he eventually concluded that the president was an unmatched leader, very near being a perfect man. Edwin Stanton, who had treated Lincoln with contempt at their initial acquaintance, developed a great respect for the commander in chief and was unable to control his tears for weeks after the presidents death. Even Chase, whose restless ambition for the presidency was never realized, at last acknowledged that Lincoln had outmaneuvered him.