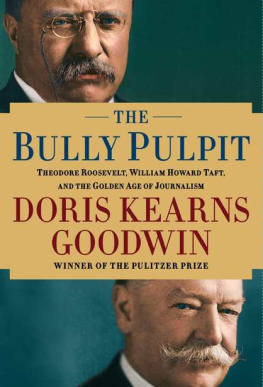

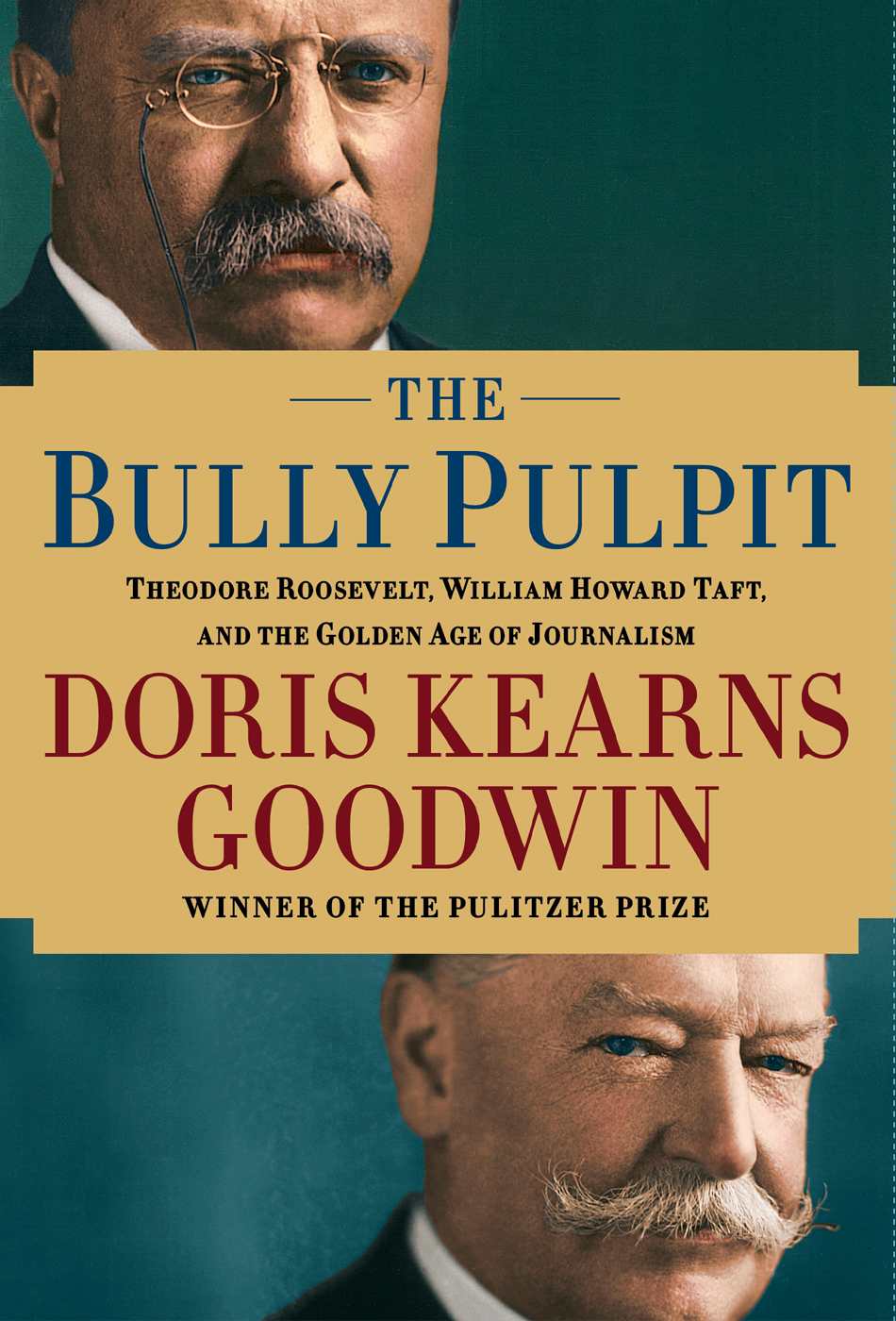

Doris Kearns Goodwin - The Bully Pulpit: Theodore Roosevelt, William Howard Taft, and the Golden Age of Journalism

Here you can read online Doris Kearns Goodwin - The Bully Pulpit: Theodore Roosevelt, William Howard Taft, and the Golden Age of Journalism full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2013, publisher: Simon & Schuster, genre: Detective and thriller. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:The Bully Pulpit: Theodore Roosevelt, William Howard Taft, and the Golden Age of Journalism

- Author:

- Publisher:Simon & Schuster

- Genre:

- Year:2013

- Rating:4 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

The Bully Pulpit: Theodore Roosevelt, William Howard Taft, and the Golden Age of Journalism: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "The Bully Pulpit: Theodore Roosevelt, William Howard Taft, and the Golden Age of Journalism" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

These unnervingly familiar headlines serve as the backdrop for Doris Kearns Goodwins highly anticipated The Bully Pulpita dynamic history of the first decade of the Progressive era, that tumultuous time when the nation was coming unseamed and reform was in the air.

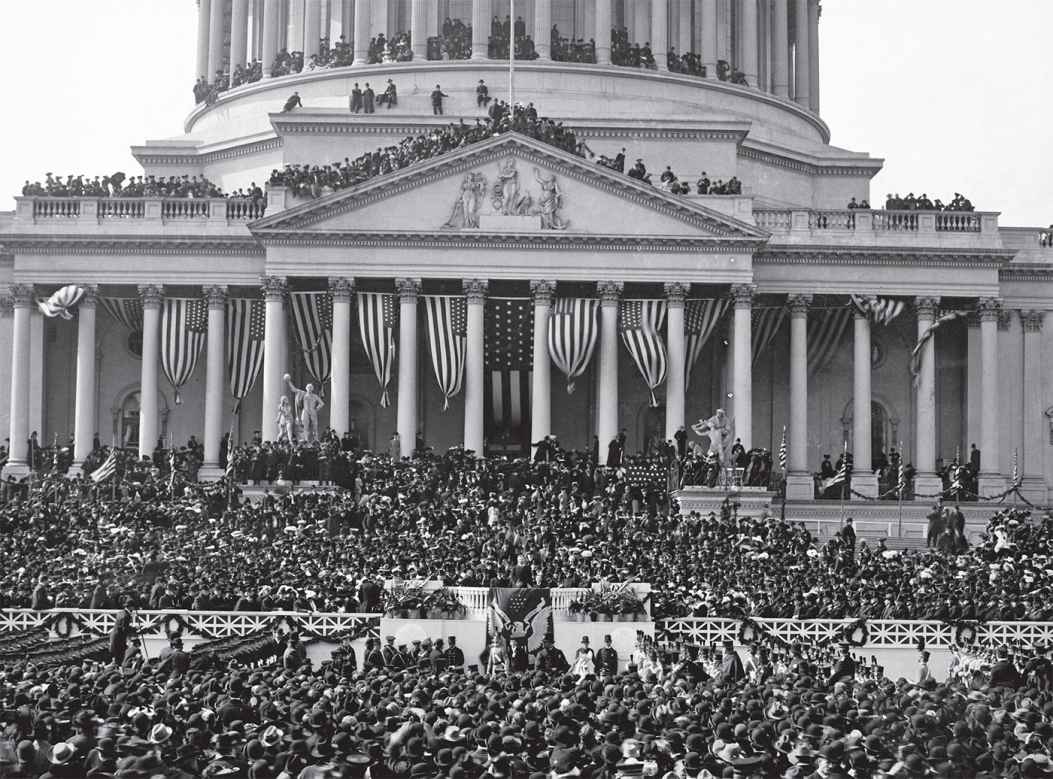

The story is told through the intense friendship of Theodore Roosevelt and William Howard Tafta close relationship that strengthens both men before it ruptures in 1912, when they engage in a brutal fight for the presidential nomination that divides their wives, their children, and their closest friends, while crippling the progressive wing of the Republican Party, causing Democrat Woodrow Wilson to be elected, and changing the countrys history.

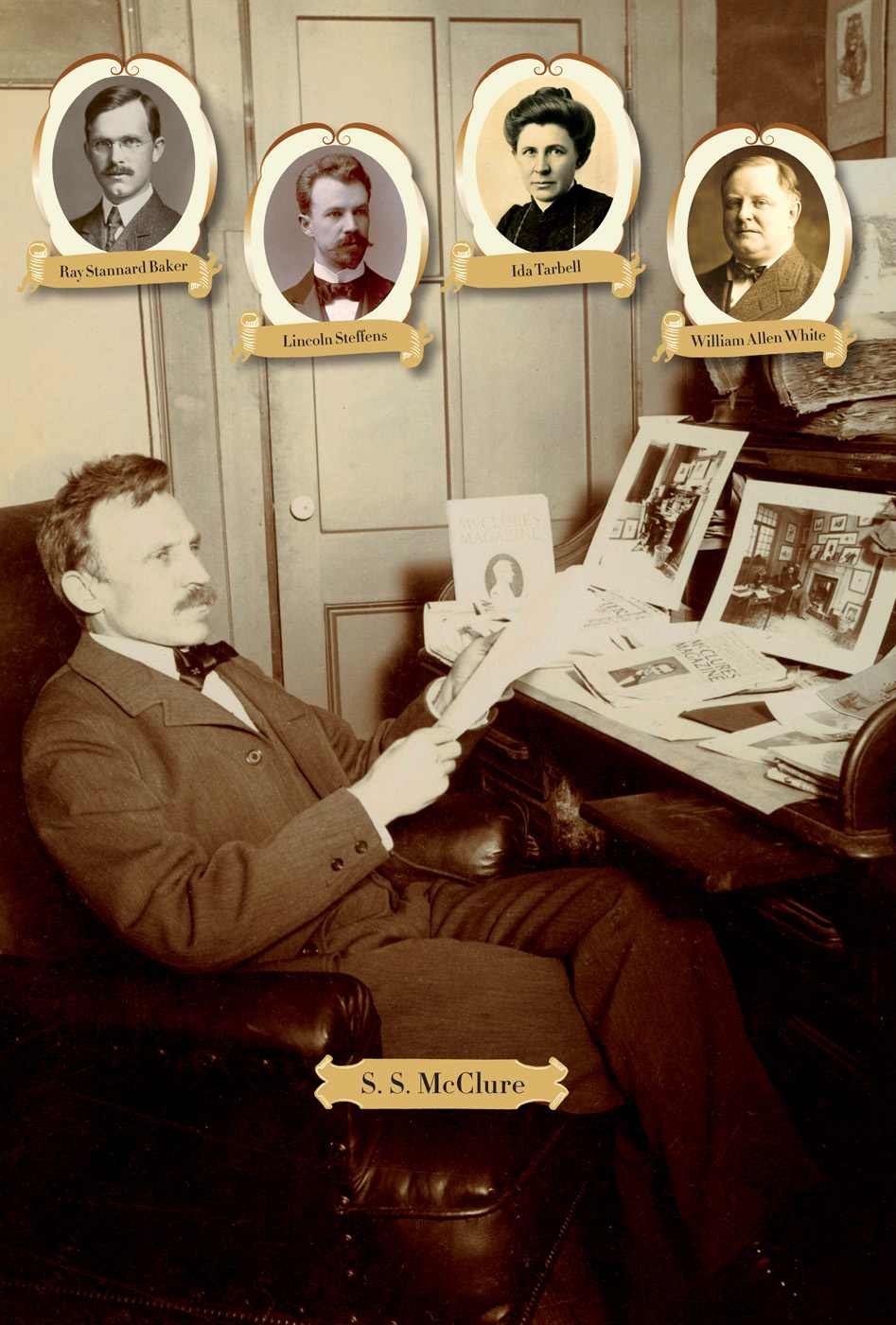

The Bully Pulpit is also the story of the muckraking press, which arouses the spirit of reform that helps Roosevelt push the government to shed its laissez-faire attitude toward robber barons, corrupt politicians, and corporate exploiters of our natural resources. The muckrakers are portrayed through the greatest group of journalists ever assembled at one magazineIda Tarbell, Ray Stannard Baker, Lincoln Steffens, and William Allen Whiteteamed under the mercurial genius of publisher S. S. McClure.

Goodwins narrative is founded upon a wealth of primary materials. The correspondence of more than four hundred letters between Roosevelt and Taft begins in their early thirties and ends only months before Roosevelts death. Edith Roosevelt and Nellie Taft kept diaries. The muckrakers wrote hundreds of letters to one another, kept journals, and wrote their memoirs. The letters of Captain Archie Butt, who served as a personal aide to both Roosevelt and Taft, provide an intimate view of both men.

The Bully Pulpit, like Goodwins brilliant chronicles of the Civil War and World War II, exquisitely demonstrates her distinctive ability to combine scholarly rigor with accessibility. It is a major work of historyan examination of leadership in a rare moment of activism and reform that brought the country closer to its founding ideals.

Doris Kearns Goodwin: author's other books

Who wrote The Bully Pulpit: Theodore Roosevelt, William Howard Taft, and the Golden Age of Journalism? Find out the surname, the name of the author of the book and a list of all author's works by series.

CONTENTS

CONTENTS