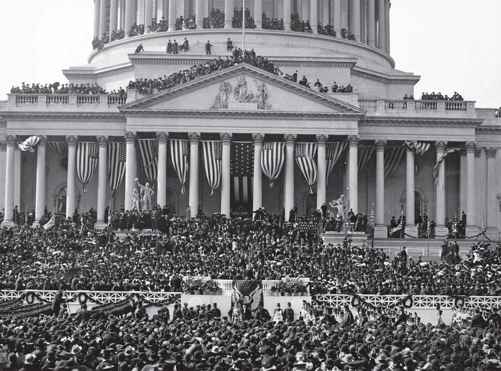

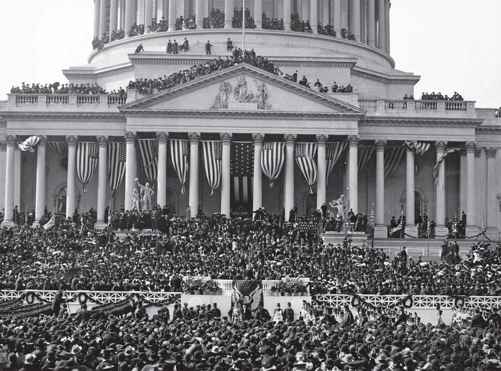

On March 4, 1905, the day of Theodore Roosevelts inauguration, the skies over the Capitol were sunny and clear; Roosevelt luck had brought Roosevelt weather, Washingtonians remarked. Thank you for downloading this Simon & Schuster eBook.

Join our mailing list and get updates on new releases, deals, bonus content and other great books from Simon & Schuster. CLICK HERE TO SIGN UP or visit us online to sign up at

eBookNews.SimonandSchuster.com

CONTENTS

CONTENTS

To Alice Mayhew and Linda Vandegrift

PREFACE

PREFACE

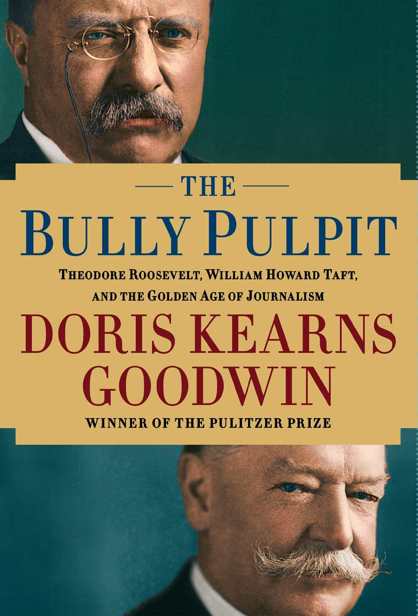

I BEGAN THIS BOOK SEVEN YEARS ago with the notion of writing about Theodore Roosevelt and the Progressive era. This desire had been kindled nearly four decades earlier when I was a young professor teaching a seminar on the progressives. There are but a handful of times in the history of our country when there occurs a transformation so remarkable that a molt seems to take place, and an altered country begins to emerge. The turn of the twentieth century was such a time, and Theodore Roosevelt is counted among our greatest presidents, one of the few to attain that eminence without having surmounted some pronounced national crisisrevolution, war, widespread national depression.

To be sure, Roosevelt had faced a pernicious underlying crisis, one as pervasive as any military conflict or economic collapse. In the wake of the Industrial Revolution, an immense gulf had opened between the rich and the poor; daily existence had become more difficult for ordinary people, and the middle class felt increasingly squeezed. Yet by the end of Roosevelts tenure in the White House, a mood of reform had swept the country, creating a new kind of presidency and a new vision of the relationship between the government and the people. A series of anti-trust suits had been won and legislation passed to regulate railroads, strengthen labor rights, curb political corruption, end corporate campaign contributions, impose limits on the working day, protect consumers from unsafe food and drugs, and conserve vast swaths of natural resources for the American people. The question that most intrigued me was how Roosevelt had managed to rouse a Congress long wedded to the reigning concept of laissez-fairea government interfering as little as possible in the economic and social life of the peopleto pass such comprehensive measures.

The essence of Roosevelts leadership, I soon became convinced, lay in his enterprising use of the bully pulpit, a phrase he himself coined to describe the national platform the presidency provides to shape public sentiment and mobilize action. Early in Roosevelts tenure, Lyman Abbott, editor of The Outlook , joined a small group of friends in the presidents library to offer advice and criticism on a draft of his upcoming message to Congress. He had just finished a paragraph of a distinctly ethical character, Abbott recalled, when he suddenly stopped, swung round in his swivel chair, and said, I suppose my critics will call that preaching, but I have got such a bully pulpit. From this bully pulpit, Roosevelt would focus the charge of a national movement to apply an ethical framework, through government action, to the untrammeled growth of modern America.

Roosevelt understood from the outset that this task hinged upon the need to develop powerfully reciprocal relationships with members of the national press. He called them by their first names, invited them to meals, took questions during his midday shave, welcomed their company at days end while he signed correspondence, and designated, for the first time, a special room for them in the West Wing. He brought them aboard his private railroad car during his regular swings around the country. At every village station, he reached the hearts of the gathered crowds with homespun language, aphorisms, and direct moral appeals. Accompanying reporters then extended the reach of Roosevelts words in national publications. Such extraordinary rapport with the press did not stem from calculation alone. Long before and after he was president, Roosevelt was an author and historian. From an early age, he read as he breathed. He knew and revered writers, and his relationship with journalists was authentically collegial. In a sense, he was one of them.

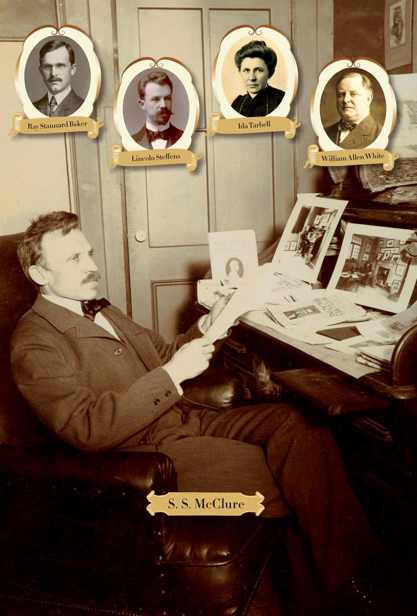

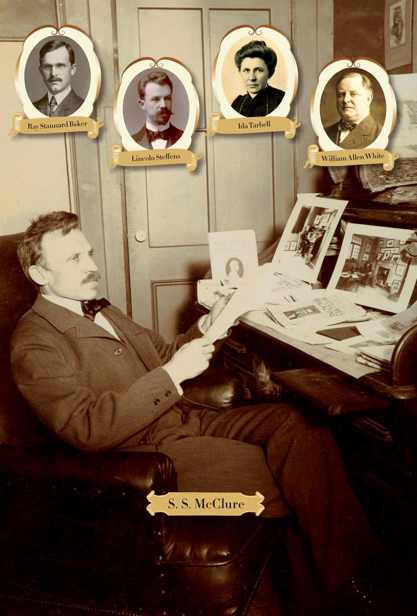

While exploring Roosevelts relationship with the press, I was especially drawn to the remarkably rich connections he developed with a team of journalistsincluding Ida Tarbell, Ray Stannard Baker, Lincoln Steffens, and William Allen Whiteall working at McClures magazine, the most influential contemporary progressive publication. The restless enthusiasm and manic energy of their publisher and editor, S. S. McClure, infused the magazine with a spark of genius, even as he suffered from periodic nervous breakdowns. The story is the thing, Sam McClure responded when asked to account for the methodology behind his publication. He wanted his writers to begin their research without preconceived notions, to carry their readers through their own process of discovery. As they educated themselves about the social and economic inequities rampant in the wake of teeming industrialization, so they educated the entire country.

Together, these investigative journalists, who would later appropriate Roosevelts derogatory term muckraker as a badge of honor, produced a series of exposs that uncovered the invisible web of corruption linking politics to business. McClures formulagiving his writers the time and resources they needed to produce extended, intensively researched articleswas soon adopted by rival magazines, creating what many considered a golden age of journalism. Collectively, this generation of gifted writers ushered in a new mode of investigative reporting that provided the necessary conditions to make a genuine bully pulpit of the American presidency. It is hardly an exaggeration to say that the progressive mind was characteristically a journalistic mind, the historian Richard Hofstadter observed, and that its characteristic contribution was that of the socially responsible reporter-reformer.

P ERHAPS MOST SURPRISING TO ME in my own process of research was the discovery that Roosevelts chosen successor in the White House, William Howard Taft, was a far more sympathetic, if flawed, figure than I had realized. Scholarship has long focused on the rift in the relations between the two men during the bitter 1912 election fight, ignoring their career-long, mutually beneficial friendship. Throughout the Roosevelt administration, Taft functioned, in Roosevelts own estimation, as the central figure in his cabinet. Because it was seen as undignified for a sitting president to campaign on his own behalf, Taft served as the chief surrogate during Roosevelts 1904 presidential race, the most demanded speaker on the circuit to explain and justify the presidents positions. In an era when presidents routinely spent long periods away from Washington, crisscrossing the country on whistle-stop tours or simply vacationing, it was Taft, the secretary of warnot the secretary of state or the vice presidentwho was considered the acting President. Asked how things would be managed in his absence, Roosevelt blithely replied: Oh, things will be all right, I have left Taft sitting on the lid.

Next page

CONTENTS

CONTENTS