Table of Contents

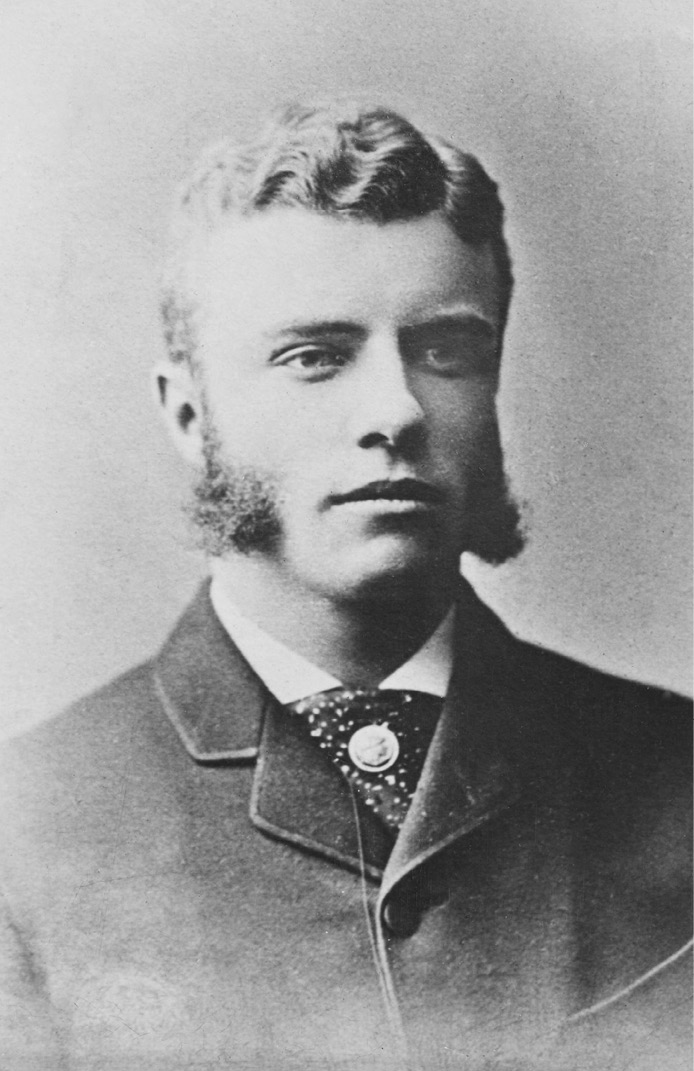

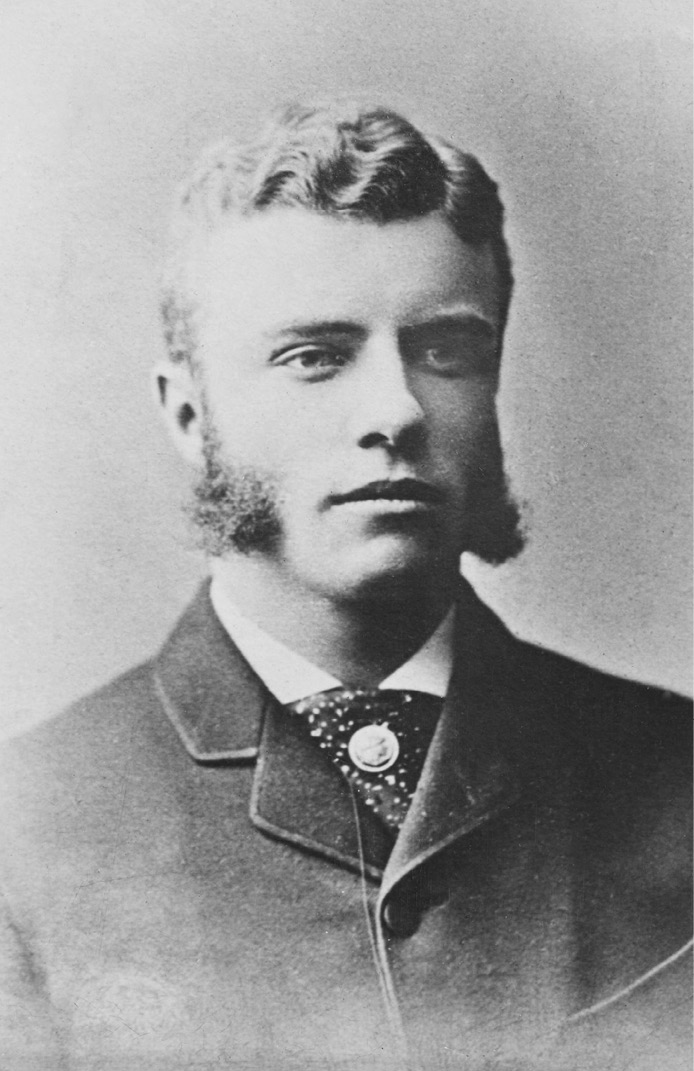

Theodore Roosevelt in 1880

Theodore Roosevelt Collection, Harvard College Library (520.12-009)

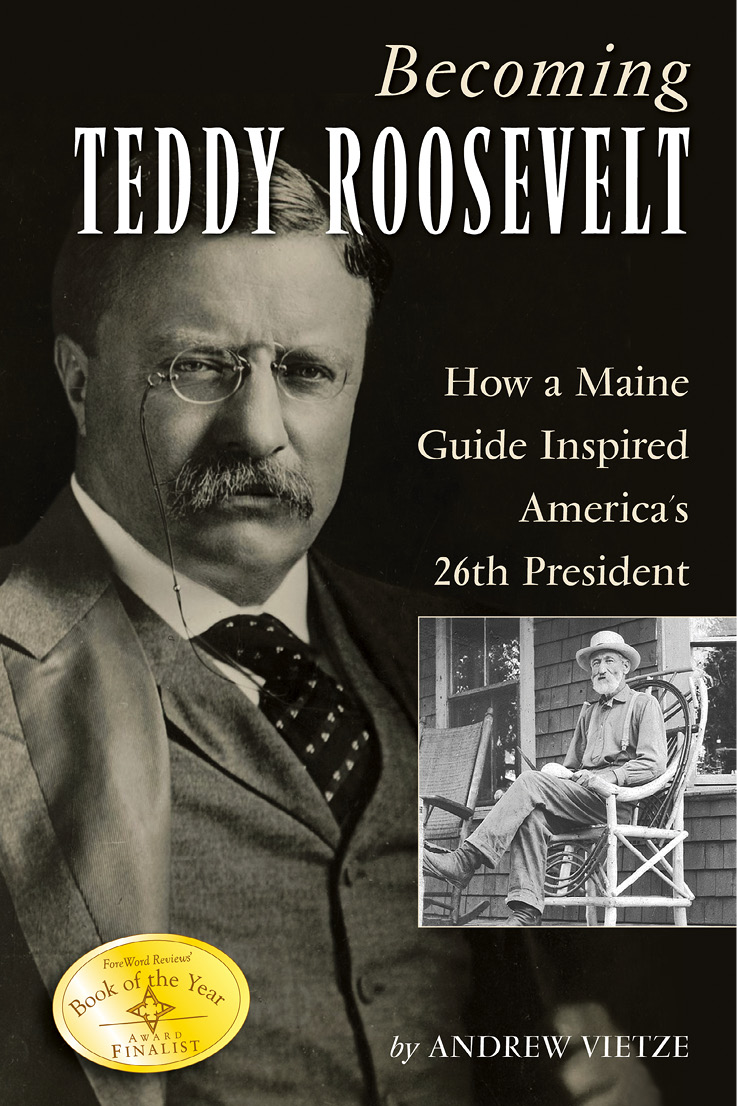

Copyright 2010 by Andrew Vietze

First Paperback Edition, 2011

ISBN: 978-1-60893-174-3

Designed by Rich Eastman

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data available upon request.

Printed in the United States of America

5 4 3 2 1

Distributed to the trade by National Book Network

For my mom and dad,

who introduced me to the woods.

For my wife, Lisa, and my boy, Gus,

without whom life wouldnt be much of an adventure.

And for my buddy Bruce White, Baxter State Park Unit 67,

whos been like a Sewall to me.

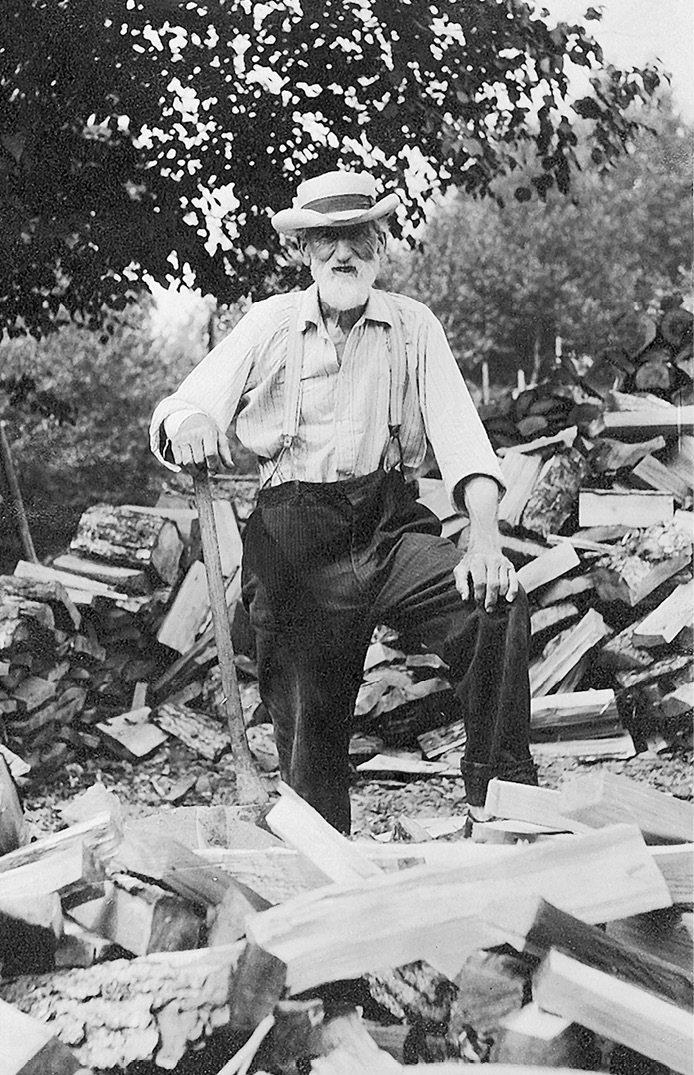

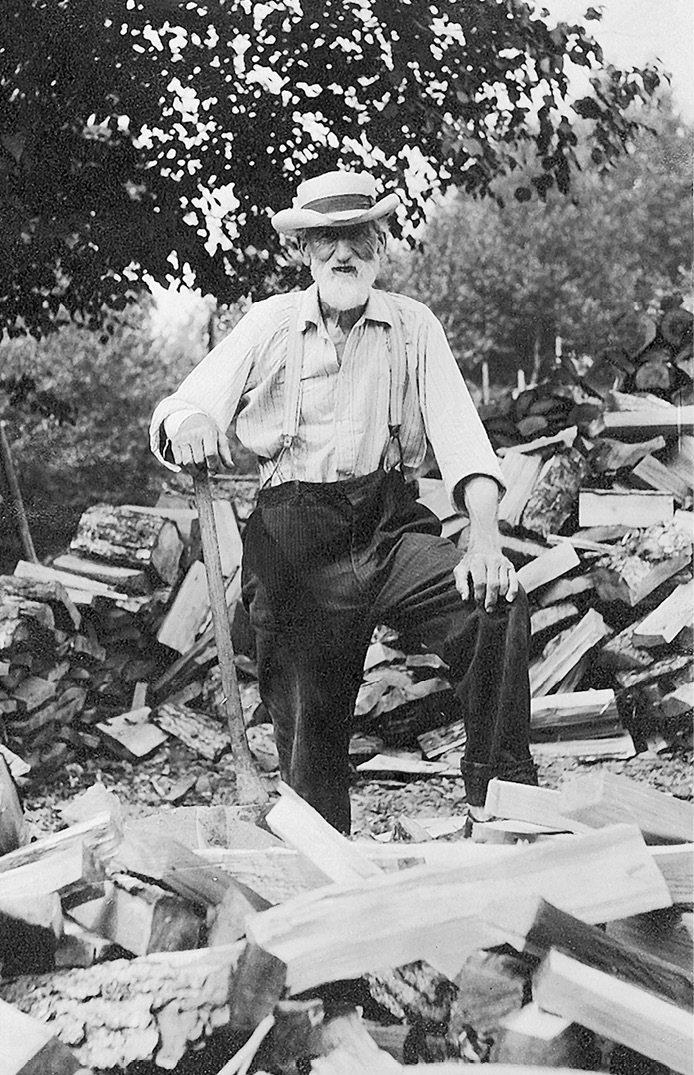

Theodore Roosevelts Maine man, William Wingate Sewall, in the 1920s

Donna Davidge-Bonham / Sewall House

Introduction

The story of Theodore Roosevelt is the story of a small boy who read about great men and decided he wanted to be like them.

Hermann Hagedorn [1]

I was never all that interested in Theodore Roosevelt. Unlike so many other history buffs, I wasnt captivated by his relentless enthusiasm, his rough-and-ready persona, his bullish pronouncements, or his toothy grin. I figured it was all caricature, and to me he was just another rich, dead president whose background of affluence and privilege had very little in common with mine.

That all changed, though, when I discovered hed climbed Mount Katahdin.

As a park ranger at Baxter State Park, the great wilderness that surrounds Katahdin with a whole universe of woodlands, I was required to read Legacy of a Lifetime , by John W. Hakola. The dry old tome tells the rather amazing tale of how Percival Baxter, once governor of Maine, assembled the 200,000-acre park that bears his name over the span of decades, piecing it together like a vast woody mosaic. And in its pages is a short account of the twenty-sixth presidents climb up the Mountain of the People of Maine back when he was a wheezing, asthmatic Harvard student. His guide was Bill Sewall, a backwoodsman from the tiny upcountry hamlet of Island Falls.

Now, this captured my attention. The appeal was twofold; as a Maine Guide and a ranger I was impressed that Roosevelt was able to summit the peakan all-day taskin what amounted to bedroom slippers, even though everyone else in his party save his guides turned back. Ever the hungry freelancer, I also figured I could sell the story of TR and Sewall to Down East . Ive done a lot of work for the Magazine of Maine over the years, and I didnt recall ever seeing word of this tale in recent times.

My editor liked the idea, and off I went, picking up the storys track and following it deep into the North Woods. I found that not only did I like Roosevelt, I liked his larger-than-life guide even better. The more I learned about Bill Sewalls grit and wit, the more I realized I wanted to know more about this man from Maine than I could contain in a mere magazine story. When the article was eventually published, it became apparent that many others wanted to know more, too.

Mine was far from the first account of the unlikely friendship that developed between the two men, but most writers dealt with it in a fairly cursory manner. In the innumerable biographies of the former president, Bill Sewall takes up only a page or two or a handful at best. Writers found him a colorful old character, but they left it at that. Something told me, though, that there was more to the story, that this was a uniquely formative relationship for the quirky young New Yorker.

Or, rather, someone told meHermann Hagedorn. A writer and poet who would eventually write several books on Roosevelt and go on to help found the Theodore Roosevelt Association, Hagedorn was TRs official biographer and knew him personally. He got his information from the most primary of sourcesRoosevelts always active mouth. Not long before the former president died in January of 1919, Hagedorn asked him to suggest some other people he should be consulting for his biography. In other words, who best knew Theodore Roosevelt?

Roosevelt sent the writer north to Island Falls, Maine, to see his old friend and guide. Before doing so, TR wrote Sewall to tell him Hagedorn was coming. There is no one who could more clearly give the account of me, when I was a young man and ever since, Roosevelt said in the letter. [2] I want you to tell him everything, good, bad and indifferent. Dont spare me the least bit. Give him the very worst side of me you can think of, and the very best side of me that is truthful. I have told Hagedorn that I thought you could possibly come nearer to putting him next me as I was seen by a close friend who worked with me when I had bark on than anyone else could. Tell him about our snow-shoe trips; tell him about the ranch. Tell him how we got Red Finnegan and the two other cattle thieves. Tell him everything.

And Sewall did. In his wry Yankee way, he filled the writers ear, giving Hagedorn plenty of material for his two seminal biographies of TR The Boys Life of Theodore Roosevelt and Theodore Roosevelt in the Badlands .

Hermann Hagedorn would no doubt be surprised that history hasnt followed Bill Sewall more closely, that it allowed the woodsman to disappear back into the very forests from which he emerged. In an introduction to the book Sewall himself penned about TR, Hagedorn wrote, in his typically garrulous fashion: Historians, seeking one after the other for centuries to come to explore the mysteries of the paradoxical career of Theodore Roosevelt, will have more to say of William Wingate Sewall than his Maine neighbors or even the statesmen, scientists, and men of letters who drew him into their councils, when the time came for choosing a national memorial to a great President, are likely now to realize. [3]

Strangely, though, they have never had much more to say about Sewall or his role in TRs personal development. (Perhaps they couldnt get through that sentence.) This book is not the definitive book on Theodore Roosevelts childhoodsupremely eminent historians with names like McCullough and Morris have already written thoseand makes no stab at that. Rather its an attempt to answer a simple question: Who was Bill Sewall, and why did what this son of the soil had to say matter to Theodore Roosevelt?

Somehow the counsel of Island Fallss most famous guide has faded with the passage of time. This might be because the very virtues he championedthe importance of character and integrity, the strength of the individual, the richness and beauty of small-town life, the enlightenment that the academy of nature can providehave also diminished in stature in this Information Age.

With Wi-Fi transmitting the ideas of the urban elites to every corner of the country, and children suffering from nature-deficit disorder, weve all become city folk like Roosevelt. In this age of convenience, when we can download whatever nugget of information we want instantly and adjust the climate control in our homes and cars in moments, weve gotten soft and forgotten how to shift for ourselves. We could all stand for a tramp in the woods again, to feel the restorative value of the outdoors, to learn a little self-sufficiency, to remember that humans may be intellectual animals, but theyre still animals.