HEIR TO THE

EMPIRE CITY

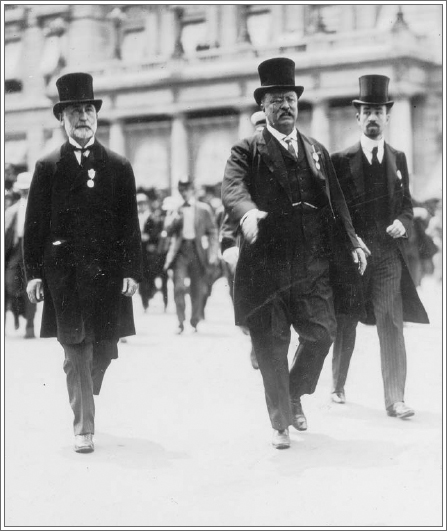

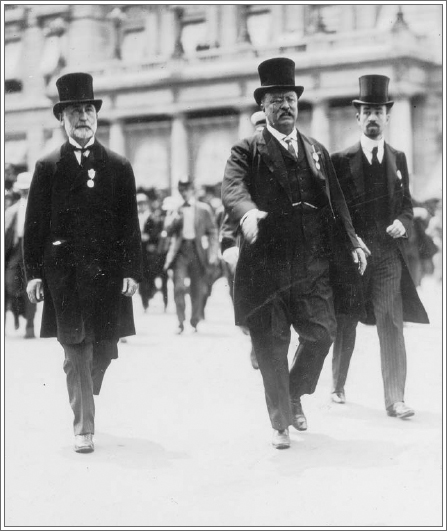

From left to right: Mayor William Jay Gaynor, Theodore Roosevelt, and Cornelius Vanderbilt III on the day of Roosevelts New York homecoming, June 18, 1910. (Courtesy of the Theodore Roosevelt Collection, Harvard College Library)

Copyright 2014 by Edward P. Kohn

Published by Basic Books,

A Member of the Perseus Books Group

All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. No part of this book may be reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews. For information, address Basic Books, 250 West 57th Street, 15th Floor, New York, NY 10107.

Books published by Basic Books are available at special discounts for bulk purchases in the United States by corporations, institutions, and other organizations. For more information, please contact the Special Markets Department at the Perseus Books Group, 2300 Chestnut Street, Suite 200, Philadelphia, PA 19103, or call (800) 810-4145, ext. 5000, or e-mail .

Designed by Cynthia Young

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Kohn, Edward P. (Edward Parliament), 1968

Heir to the Empire City : New York and the making of Theodore Roosevelt /

Edward P. Kohn.

pages cm

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-465-06975-0 (e-book)

1. Roosevelt, Theodore, 18581919. 2. PoliticiansNew York (State)Biography. 3. New York (N.Y.)History18651898. 4. New York (N.Y.)Biography. 5. PresidentsUnited StateBiography. I. Title.

E757.K64 2013

973.91'1092--dc23

[B]

2013032232

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

For Pelin

Contents

T HEODORE ROOSEVELTS path to the White House may have gone through the West, but it did not start there.

Biographers of Theodore Roosevelt have come to a consensus that he was really a westerner, or a man torn between East and West. The person most responsible for this image was Roosevelt himself. In his writings, including his 1913 Autobiography, he carefully painted a portrait of himself as a rancher, hunter, and cowboy. Before he ever charged up Cubas San Juan Heights, Roosevelt had published several books reflecting his western experience, including his four-volume history The Winning of the West. Roosevelts actions in Cuba in 1898 only underscored his western image, as did Frederic Remingtons famous painting Charge of the Rough Riders at San Juan Hill, which portrayed him as a leader on horseback in a broad-brimmed hat, waving a six-shooter. After becoming president, Roosevelt published Outdoor Pastimes of an American Hunter, a 1905 work, and his 1913 memoirs seemed to leave little doubt to future historians of the impact of his Dakota days: It was a fine, healthy life, too, he wrote. It taught a man self-reliance, hardihood, and the value of instant decision. Without his time in the West, Roosevelt stated repeatedly during his life, he never would have been president.

Professional historians took up the theme almost immediately. Roosevelts first biographer, Hermann Hagedorn, published Roosevelt in the Bad Lands in 1921, only two years after the former presidents death. Since then, Roosevelt has appeared in books as a western phenomenon. His hunting and ranching have been credited not just with driving his later conservation efforts, but also with influencing his domestic and even his foreign policies as president.

But, however romantic, the western image of Roosevelt is incorrect, and it ignores the central facts of Roosevelts life. Theodore Roosevelt was born in Manhattan, not the West. He was raised in the most thoroughly urban setting of late nineteenth-century America. Roosevelts grandfather was one of New York Citys richest men, and his father one of its leading philanthropists. Even his love of nature and animals began in an urban rather than a rural setting. In the city, Roosevelt collected mice and frogs and studied taxidermy. In the attic of his Gramercy Park home, he established the Roosevelt Museum of Natural History, a precocious mirror to one of the institutions his father helped to found, the American Museum of Natural History, which opened its doors to its first exhibits in its temporary Central Park quarters when Roosevelt was just twelve years old. And late nineteenth-century New York was not completely urban. With backyards full of chicken coops and exotic animals kept as pets, the young Roosevelt did not have to go far to immerse himself in flora and fauna.

Theodore Roosevelts early political career was also firmly rooted in New York City, not the Dakota Territory. He served for three years in the New York State Assembly representing his uptown brownstone district. In Albany, he sat on the Cities Committee that wrote laws for New York City, which did not then enjoy home rule. He ran unsuccessfully for mayor of New York in 1886. Later, his first act as US civil service commissioner was to return to the city of his birth and attack corruption in the New York Custom House. He served as New York City police commissioner for two years. Then, as governor, he constantly dealt with the affairs of New York City and the Republican boss Thomas Collier Platt, who held court at Manhattans Fifth Avenue Hotel. As president, Roosevelt continued to concern himself with the minutiae of New York politics and government, from mayoral elections to police promotions and from Republican politics to the war on vice. Even while occupying the White House, Theodore Roosevelt was still a New Yorker, and his politics reflected this. Roosevelt was no agrarian populist from west of the Mississippi. He was an urban progressive, concerned with such issues as civil service, municipal reform, and political machines.

In addition to writing about the West, Roosevelt also wrote about urban affairs. In 1891, he published a history of New York from the time of its discovery by Henry Hudson in 1609. Years before he wrote his famous 1894 essay True Americanism in The Forum, Roosevelt wrote in New York that the most important lesson taught by the history of New York City is the lesson of Americanismthe lesson that he among us who wishes to win honor in our life, and to play his part honestly and manfully, must be indeed an American in spirit and purpose, in heart and thought and deed. In 1895, while he was police commissioner, Roosevelt penned the essay The City in Modern Life, as well as another essay entitled The Higher Life of American Cities. Throughout his career, he wrote essays on machine politics in New York, the New York police, and efforts at reform. In writing about the West, Roosevelt adroitly tapped into Americans romantic obsession in order to sell books and promote an image of himself, whereas in writing about New York, he arguably wrote about the experiences and ideas closest to his heart.

Roosevelts political career grew and developed in concert with the city. During his lifetime, the population of New York City grew from 800,000 to an astonishing 5.5 million, which made it the second largest city in the world. The expanding population strained basic city services, such as water and sanitation. Limited housing forced the working class into ever more densely packed tenements, which became visible and decrepit symbols of poverty, crime, and disease. Such areas became fertile ground for social reformers, and political reformers, such as Roosevelt, took aim at the city government. A growing city and its infrastructure meant that New York politicians oversaw increasingly large budgets. Inevitably much of this money found its way into the pockets of unscrupulous city officials and their allies. There was never enough revenue to finance the building of roads, bridges, parks, and courthouses, and so the city depended increasingly on raising money by issuing bonds. Such bloated debt caused one New York mayor to note in 1882 that the city owed to creditors the equivalent of about 10 percent of the total value of all Manhattan real estate. At the same time, it became harder to understand who was actually in charge in the city. A shadowy, unelected Board of Aldermen checked the policies and appointments of the mayor, who was elected to only a two-year term. In turn, the party bosses, especially from the city Democratic organization known as Tammany Hall, manipulated mayors, aldermen, and city officials. Throughout his career in the city and Albany, Roosevelt championed measures that increased the executive power of the mayor while seeking to undermine the influence of party bosses and their puppets on the Board of Aldermen.

Next page