T HEODORE R OOSEVELT AND THE A SSASSIN

A LSO BY G ERARD H ELFERICH

Humboldts Cosmos: Alexander von Humboldt and the Latin American Journey That Changed the Way We See the World

High Cotton: Four Seasons in the Mississippi Delta

Stone of Kings: In Search of the Lost Jade of the Maya

T HEODORE R OOSEVELT AND THE A SSASSIN

Madness, Vengeance, and the Campaign of 1912

G ERARD H ELFERICH

LYONS PRESS

Guilford, Connecticut

An imprint of Globe Pequot Press

Copyright 2013 by Gerard Helferich

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, except as may be expressly permitted in writing from the publisher. Requests for permission should be addressed to Globe Pequot Press, Attn: Rights and Permissions Department, PO Box 480, Guilford, CT 06437.

Lyons Press is an imprint of Globe Pequot Press.

Photos on pages 196 and 198 are in the public domain. All other photos courtesy of the Library of Congress unless otherwise noted.

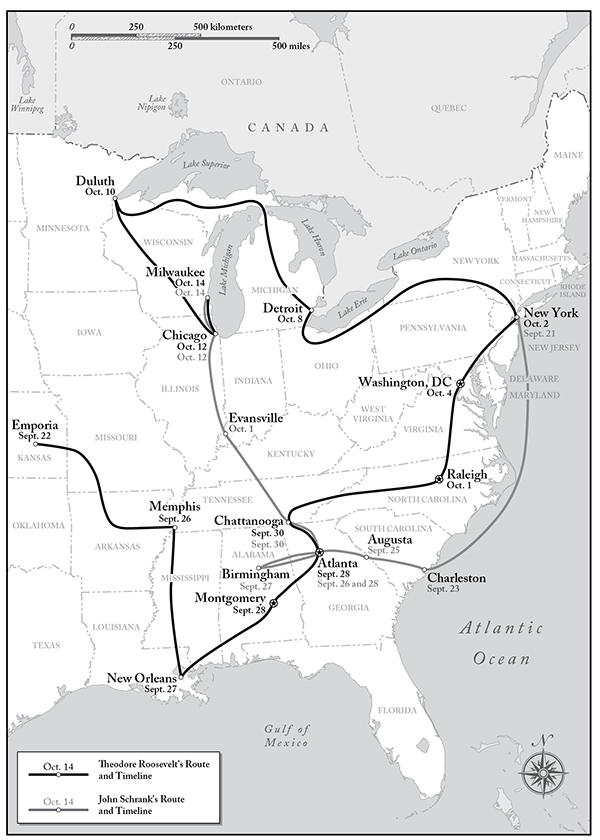

Map by Melissa Baker Morris Book Publishing, LLC

Project editor: Meredith Dias

Layout artist: Sue Murray

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Helferich, Gerard.

Theodore Roosevelt and the assassin : madness, vengeance, and the

campaign of 1912 / Gerard Helferich.

pages cm

Summary: Rich with local color, period detail, and a fully realized

historical and political backdrop, the forgotten story of the lone,

fanatical assailant who stalked Theodore Roosevelt on the 1912

presidential campaign trail until the evening of October 14 in

Milwaukee, when he shot the Bull Moose in the chest from ten feet

awayProvided by publisher.

E-ISBN 978-1-4930-0076-0

1. Roosevelt, Theodore, 1858-1919Assassination attempt, 1912. 2.

Schrank, John Flammang, 1876-1943. 3. PresidentsUnited

StatesElection1912. I. Title.

E765.H45 2013

973.911092dc23

2013019156

W ITH GRATITUDE AND LOVE TO MY EXTENDED FAMILY OF BROTHERS AND SISTERS B ILL AND C AROL, M ARLENE AND B OB, L ISA AND J OEL, AND D EBBIE AND J AN

C ONTENTS

The Travels of Theodore Roosevelt and John Schrank, September 21October 14, 1912.

P ROLOGUE

Avenge My Death!

Sunday, September 15, 1901

The young, heavyset man found himself alone in a cavernous room. Eerily quiet, the dim chamber was crowded with wreaths and sprays of flowers exuding an overpowering, syrupy odor. In the center of the room rested an open coffin of polished Santo Domingo mahogany. Inside the casket lay a portly, middle-aged man dressed in a black suit, a white shirt with a stiff collar, and a slender black bow tie. The mans thinning gray hair was oiled, revealing a high forehead, owlish brows, and a square, cleft chin. Even in death, the features wore a stolid but kindly expression, revealing no trace of malice, no hint of the suffering hed endured. The young man recognized the face immediately. It belonged to President William McKinley, who had perished early the previous morning.

For the past week, the young man had pored over the newspapers, immersing himself in the details of the tragedy. The president had been attending the Pan-American Exposition in Buffalo, a lavish spectacle meant to showcase American prosperity at the dawn of the twentieth century, with fanciful lagoons and canals, a midway of rides and attractions, and massive exhibition halls dedicated to sciences such as agriculture and mining, all bathed in electric light from the newly harnessed power of Niagara Falls. But while Buffalo had begun to call itself the City of Light, its exposition would forever after be linked with something dark and hideous.

The fair had opened in May, and President McKinley had planned to make an official visit in June. But when the First Lady had another of her attacks, the trip was postponed until September. The president finally arrived in Buffalo on Wednesday the fourth, and the following day delivered a fine speech on one of his pet themes, the need to expand overseas markets for American goods. On Friday, declared Presidents Day at the exposition, he boarded a train to view the spectacular Falls, twenty miles away, then returned to Buffalo and prepared to greet the public at the expositions Temple of Music. Fearing for his chiefs safety in the throng, McKinleys personal secretary had canceled the reception twice, but the president had insisted on attending. No one would wish to hurt me, hed scoffed. Besides, the president enjoyed meeting the public. Everyone in that line has a smile and a cheery word, he said. They bring no problems with them; only good will.

William McKinley had coasted to reelection less than a year before, on the slogan Prosperity at Home and Prestige Abroad. The economy had finally recovered from the Panic of 1893, the worst financial depression the nation had ever seen. Thanks to its swift, seemingly effortless victory in the Spanish-American War, the country had won strategic possessions in the Caribbean and the Pacific and had joined the ranks of the worlds great powers. By the time the Temple of Musics doors opened at 4:00 p.m., a queue had been waiting for hours to shake the popular presidents hand.

The Temple was the expositions principal auditorium, designed in the Italian Renaissance style and set beside the fairs central Fountain of Abundance. The exterior was painted soft yellow, trimmed with red and gold, and topped by a sky-blue dome. At each of the buildings four corners opened a graceful arched doorway, surmounted by a plaster statue representing a different musical genre. Outside the east entrance this afternoon, waiting with the rest of the crowd under the warm September sun, stood a mill worker named Leon Czolgosz.

Born in Michigan, the son of Polish immigrants, the twenty-eight-year-old Czolgosz had lived most of his life in McKinleys home state of Ohio. Hed arrived in Buffalo the week before and had registered in a rooming house under the name Fred Nieman, saying hed come to sell souvenirs at the fair, though none of the other boarders had noticed any evidence of mercantile activity. Keeping to himself, the newcomer seemed to spend most of his time hunched over the daily newspapers.

Several years ago, after losing his job during a strike at a Cleveland wire mill, Czolgosz had been drawn to the radical philosophy of anarchism. Dedicated to fomenting revolution and establishing an egalitarian and stateless society, anarchists subscribed to the propaganda of the deed, the belief that the most potent way to advance their cause was through spectacular acts of violence such as bombings and assassinations. Over the past two decades, anarchists had orchestrated dozens of acts of terrorism, especially in Europe, where they had killed Russian Czar Alexander II, French President Marie Franois Sadi Carnot, Spanish Prime Minister Antonio Cnovas del Castillo, and, just the year before, King Umberto I of Italy.

The United States had also seen two presidents assassinated over the past thirty-six years. But the first, Abraham Lincoln, had been a casualty of civil war. And the other, James Garfield, had been shot by a lunatic named Charles Guiteau, who thought to claim the presidency for himself. Neither of these domestic assassins was an anarchist, wishing to abolish all government. Yet even as Americans celebrated the new century, the nation was deeply divided. Over the past several decades, as the country had grown more industrial, more urban, and more ethnically diverse, huge monopolistic trusts such as John D. Rockefellers Standard Oil and J. P. Morgans U.S. Steel had come to dominate the nations commerce and, increasingly, its politics, until it seemed that the interests of the wealthy and powerful had eclipsed the needs of working people. And into this broken soil were sown the fertile seeds of anarchy.