Table of Contents

To my sister, with whom I shared

my strange and wonderful childhood

PREFACE

I was born five and half months after Black Tuesday, when the crash of the New York Stock Exchange in October 1929 paved the way not only for the Great Depression but also for the election of my grandfather as president of the United States. My mother, Anna Roosevelt Dall, my sister (also named Eleanor but known as Sis), and I soon joined my grandparents in their new residence, the White House, in the wake of my parents separation. We needed a roof over our heads, my mother explained. History had my family in its grip, and I had no choice but to go along for the ride.

When he took office in 1933, replacing the far-from-charismatic Herbert Hoover, Franklin Delano Roosevelt instantly claimed center stage, as he always had. At home in the White House as no other president before him, he projected a natural, seductive radiance that no one could resist. Everyone around him, from the most distinguished members of his circle to his young grandchildren, became supporting players. We were all more than willing to bask in his limelight.

For our part, my sister and I instantly turned into the countrys First Grandchildren. Though we were used to the intrusions of waving newspaper reporters and the flare of flashbulbs, moving from New York to the White House family quarters was something else altogether. The press milked the phenomenon of the towheaded Roosevelt moppets, and we became a full-blown, pint-sized double act. My family called me Buzzie, and our tabloid moniker became Sistie and Buzziepronounced as one word, Sistie-and-Buzzie. Soon we were as familiar as five-year-old movie star Shirley Temple to a nation hungry for distraction from breadlines and boxcars.

During the twelve years of my grandfathers tenure as president, Sis and I bounced from coast to coast, following our mothers criss-crossing path. She had remarried in 1935, and in 1937 we moved to Seattle so that she and my stepfather could work for William Randolph Hearsts Post-Intelligencer. Throughout this time, we returned regularly to the White House and to the Roosevelt family home at Hyde Park, New York. Any sense I had of routine and stability was rooted in those two places. The Big House in Hyde Park and the White House were, I felt, my real homes. As a teenager they were more than that; they were my school. I received my real education by listening closely to my grandparents and their friends conversing over the dining room table.

Franklin and Eleanor Roosevelt were my Papa and Grandmre, and they were the most influential figures in my life. Both of my maternal grandparents possessed complicated natures; they were difficult to penetrate. Still, for me they were human beings, not mythological figures. Moreover, they became, for me, surrogate parents, as was my great-grandmother, Sara Delano Roosevelt. I can still clearly recall my grandmothers meaningful glances when I became too enthralled with some White House ceremonysuch attention was for the president, I was reminded. And I can hear my grandfathers comical readings of the funnies as we sat on his bed while he ate breakfast each morning, his aides standing around laughing at FDRs hamming it up.

I inhabited my grandparents world from the time I was three until I was fifteen. It was an immense and wonderful privilege. Yet the experience, as one might expect, had a double edge. All of the people important to me during my childhood, indeed everyone in the orbit, were strongly affected by living and working so close to the magnetic personalities of my grandfather and grandmother. I was no exception. Life outside the protectiveand isolatedWhite House cocoon became hugely distorted, especially for an impressionable youngster like me. My early surroundings provided not only excitement and comfort but also a reality-rejecting sense of specialness, which did not stand me in good stead as I grew older.

Intoxicated by the exhilarating environments of Washington and Hyde Park, I created a dream world that protected meand became a form of addiction. In fact, as I grew older, I found it easier to inhabit this fantasy world than to develop and nurture my own strengths and talents in the real one. It has taken me a lifetime to understand my role as a tiny planet circling the dual suns of my grandparents and to accept and adjust to a world devoid of their reflected glory. Change has come only rather recentlyand it continues.

While writing this memoir, it has been a godsend to have all of my familys correspondence gathered in one place: the Roosevelt Library at Hyde Park. As I sort through photographs and letters from the early, formative period of my life, I can still feel the force of my grandparents, their irresistible allureand its disabling effects.

I remember the thrill of standing next to my grandfather as he reviewed the 1937 inaugural parade, taking off my cap whenever he did to greet the color guards of soldiers, sailors, and marines. I also remember the sorrow of leaving the White House after that inauguration, and the long train ride across the country, which felt like being exiled. It is hard, even from this distance, to break free entirely from the perspective I had at the time, or the feelings. So I am taking readers along with me, stepping through the gates of time into the distant world that formed me.

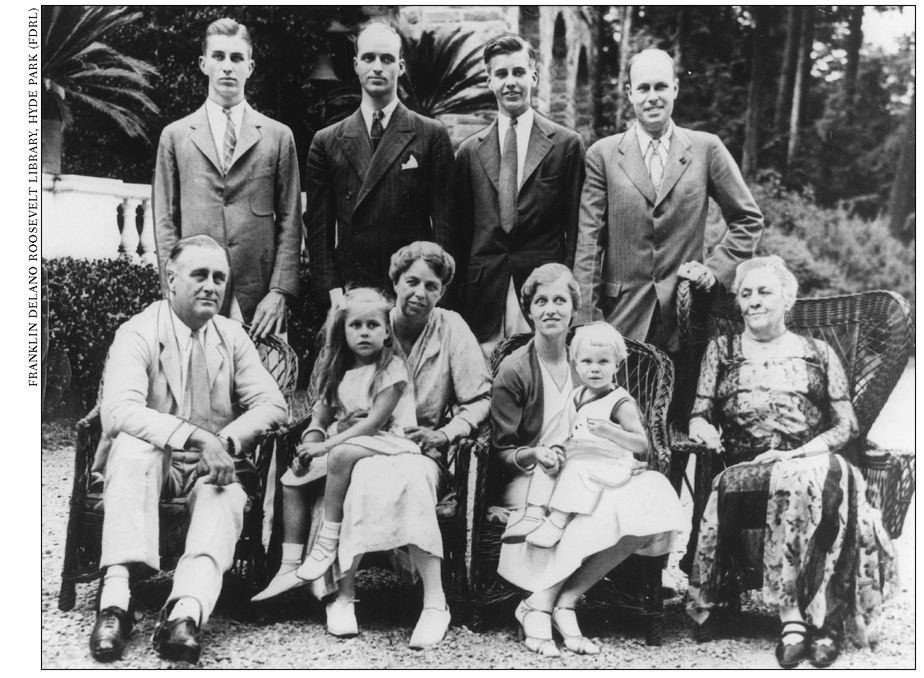

My family just after FDRs election (1933).

My family near the end of FDRs life (1945).

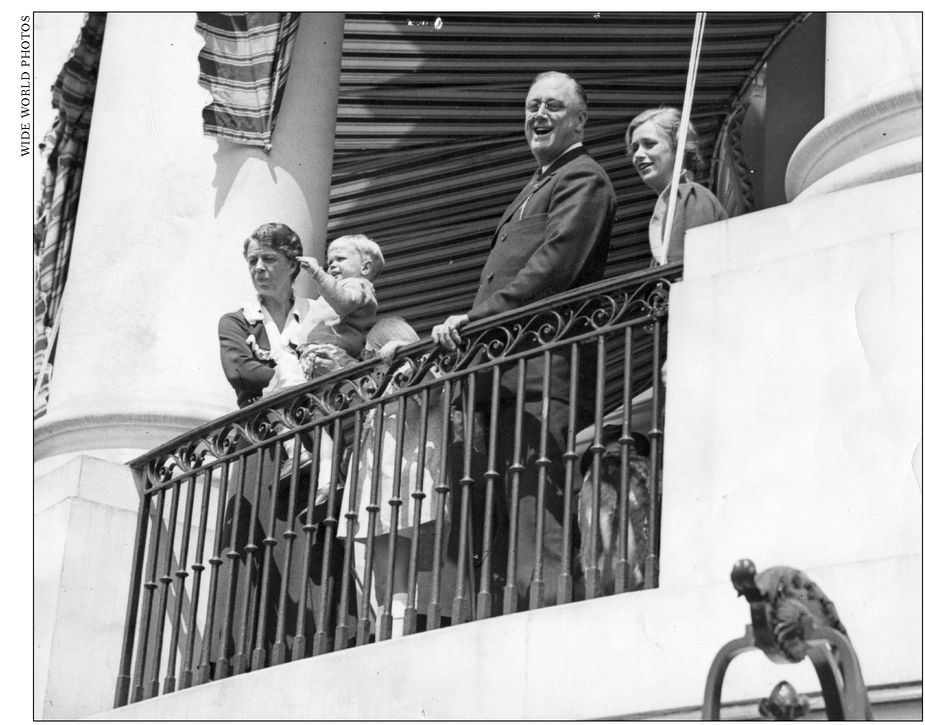

In our new homeMy sister stands with our grandfather and our mother on the White House South Portico. I am in my grandmothers arms.

CHAPTER 1

Franklin Roosevelt took the oath of office on March 4, 1933, becoming the thirty-second president of the United States. He was fifty-one years old and had been active in politics since 1910, when hed won a seat in the New York State Senate. My grandfather had made his first visit to the Executive Mansion when he was just a little boyabout the same age that I was when I moved into the White House. He was accompanying his parents, James and Sara Delano Roosevelt, to see President Grover Cleveland. Family lore has it that when he was introduced to the president, the president responded with one of those pleasantries called for in such circumstances. Looking down at young Franklin, Cleveland said, And perhaps you might one day become president.

Apparently FDR, a doted-upon only child, took the avuncular prediction to heart. Twenty years later, as a law clerk in New York City, he confided to his colleagues at Carter, Ledyard & Millburn that he hoped one day to be elected president of the United States.