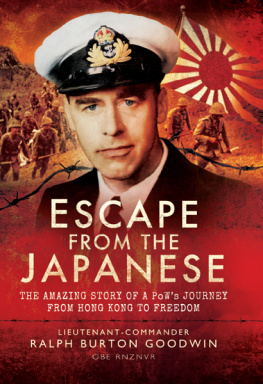

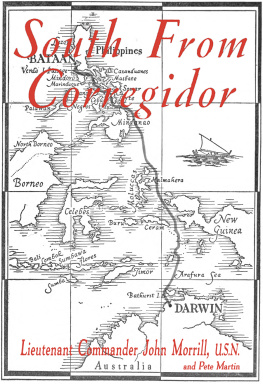

ESCAPE FROM THE JAPANESE

The Amazing Story of a PoWs Journey from Hong Kong to Freedom

First published as Hongkong Escape in 1953 by Arthur Barker Ltd., London.

This edition published in 2015 by Frontline Books,

an imprint of Pen & Sword Books Ltd,

47 Church Street, Barnsley, S. Yorkshire, S70 2AS

Copyright Lieutenant-Commander Ralph Burton Goodwin OBE, RNZNVR, 1953

The right of Lieutenant-Commander Ralph Burton Goodwin OBE, RNZNVR to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

ISBN: 978-1-84832-929-4

PDF ISBN: 978-1-84832-932-4

EPUB ISBN: 978-1-84832-931-7

PRC ISBN: 978-1-84832-930-0

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form, or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise) without the prior written permission of the publisher. Any person who does any unauthorized act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages.

CIP data records for this title are available from the British Library

Printed and bound by CPI Group (UK) Ltd, Croydon, CR0 4YY [TBC]

Typeset in 11.24/14 point Palatino

For more information on our books, please email: ,

write to us at the above address, or visit:

www.frontline-books.com

TO PHILIPPA

Publishers Note

In order to maintain the flavour of Lieutenant-Commander R.B. Goodwins escape through war-time Asia, we have retained his spelling of the numerous places referred to in the original edition of his book. There is, however, one particular exception to this, Hong Kong. Traditionally the name of this former British colony was Hongkong, but as it is more widely known as Hong Kong we have changed this throughout the text.

Contents

List of Maps

Introduction

O n the 25th day of December 1941 the rich prize of Hong Kong fell to Japanese invaders. The furious sounds of battle grumbled to a grudging silence, and all was still. There could be no Dunkirk for the beleaguered troops, the enemy was all around, and the survivors of the garrison became prisoners of war (PoW).

Before the event it was my belief that every prisoner would automatically begin to plan his escape, and that a bid for freedom would be the best contribution he could make towards the enemys defeat. Yet circumstances cloud the issues. When an escape by one or two individuals may bring severe reprisals against those left behind, the course of duty becomes confused; and when men have been weakened by systematic starvation for months, and years, thoughts of further suffering are apt to loom in distorted menace.

The merits of attempting an escape were debated long and heatedly in the prison camps in Hong Kong. From the point of view of the escaper the problem was clear-cut and simple. Success meant freedom and a return to battle; failure meant torture and execution. For those left behind the problem was confused, unpredictable, and therefore the more terrifying. Anything could happen, from a spate of tortures and executions of individuals, to a mass starvation of the whole camp. On the other hand, the Japanese might not take any of the threatened reprisals, though there were few who believed that anything but sadistic cruelty would follow an attempted escape.

When the mutterings and subdued thunders of the Second World War finally burst on an expectant world, a party of ten temporary sub-lieutenants of the New Zealand Division of the Royal Naval Volunteer Reserve sailed from Auckland to begin their war service with the Royal Navy, based at Singapore. It was my fate to be included in that party, and it was my ambition to be detailed to a motor torpedo boat. The Navy had other ideas, and I was told that my thirty-eight years made me too old for such an assignment. Almost two years of routine sea service followed, first in a minesweeper, then in an asdic patrol ship, and finally as first lieutenant in the naval tug St. Aubyn, which was delivered from Hong Kong to Aden.

From that trip I reached Singapore again late in September 1941, and after a week in HMS Kedah, a small armed merchantman, I was sent to Hong Kong to join the 2nd Motor Torpedo Boat Flotilla. Two months later Japan entered the war, and when Hong Kong surrendered it was my misfortune to be in hospital, suffering from a leg wound.

Five MTBs were still afloat, and on Christmas night, with a party of officials and all the fit personnel of the flotilla, they made a dash up the coast to Mirs Bay. There the boats were destroyed, and, guided by the Chinese Admiral Chan Chak, the party made a successful journey across China, to Chungking and freedom.

It was not until the end of February 1942 that I was fit enough to go to the overcrowded North Point Camp. That horrible place was vacated in April, when most of the men went to Shamsuipo (also referred to as Sham Shui Po) Camp in Kowloon, and most of the officers went to the Argyle Street Camp, also in Kowloon. That was to be our home for two years, and then we too were sent to Shamsuipo.

After two months in Shamsuipo I escaped on the night of the 16th-17th July 1944, and after crossing South China to Kunming, I was sent home to Auckland on leave.

Three months were spent in complete relaxation, and then I reported for duty with the MI9 Branch at British Pacific Fleet Headquarters in Sydney. That appointment gave me an opportunity to follow the fortunes of the prisoners of war in the Far East, and when Japan surrendered I went to Hong Kong with the relieving force as MI9 representative with the Prisoners of War Recovery Party.

The ships of the relieving force, under command of Admiral Sir Bruce Fraser whose flag was flying in HMS Indomitable, steamed out from Subic Bay for Hong Kong. A light breeze put dark blue colour on a smiling sea, from which the enemy had gone. But had he? We knew the fanaticism with which he fought towards the end, and there could be no carelessness yet. Aircraft flew from the carriers deck each day, and at the end of one of those exercises we saw how easily a man could lose his life.

A fighter came in, landed heavily, and broke the arrester wire. Other incoming planes were waved off until repairs were made, and then another came in to land. The day was perfect, and the pilot made a perfect landing. His tail-hook picked up the wire, but then something went wrong. Instead of running out evenly from both sides the wire ran from one side only, with the result that the fighter slewed across the deck as it slowed down. One landing-wheel ran along the scupper for some distance, and when almost stopped the plane toppled over the gunwale. Quite slowly it settled on a twin anti-aircraft gun, almost stopped there and then slipped down, nose first, into the sea. It did not sink, it floated there with its tail in the air, but for some inexplicable reason the pilot did not appear. Under a blue sky and a calm friendly sea he drowned there, one of the last casualties of a war that was already over.

We came to anchor in Hong Kong Harbour on the 30th of August 1945, and the next day I visited the Shamsuipo Camp. There all my old PoW friends were gathered, and there also was Colonel Esao Tokunaga, who had been commanding officer of all prisoner of war camps in Hong Kong. That individual, who had early been christened the White Pig, revealed the site of the graves of five prisoners who had been murdered, and he began a long justification of his own harsh treatment of the prisoners. He was most insistent that he was merely putting into practice the orders of his senior officers, and that he personally was not to blame. However, when he discovered my identity, Tokunagas inventions dried suddenly at their source, and I took the opportunity to express some of my own views of that arrogant creatures actions.

Next page