Stockwell and Minkova (1997a) provide a convenient summary of the Sievers-Bliss theory along with alternative theories. Bredehoft (2005b) is the most recent introduction to Old English metre, which can help non-specialists to scan half-lines properly on the basis of Sievers-Blisss, Russoms, and his own system.

Fulk (1997) illustrates with scepticism the prevalence of textual conservatism in recent years. For conservative attitudes, see Hoops (1932), Gneuss (1973), Stanley (1984), Niles (1994), and most recently Kiernan (2004). Among the few liberals are Sisam (1946, 1953) and Lapidge (1991, 1993, 1994). While Stanley states that every scribe, sleepy and careless as he may have been at times, knew his living Old English better than the best modern editor of Old English verse (1984: 257), Lapidge recommends that we should liberate ourselves from the premise that the work of sleepy and careless scribes should be venerated above our own judgement (1993: 157). Niles takes a conservative stance not out of a blind respect for medieval scribes but out of regard for the singers or speakers the traces of whose words may linger in scribal records (1994: 453).

Stanley (1992: 281).

The Beowulf text used is Fulk, Bjork, and Niles (2008). Other verse instances to be given later are cited chiefly from Krapp-Dobbie (193153). For short titles of prose texts as well as verse texts, I follow Healey-Venezky (1980).

In manuscript, verse texts are written continuously without line or half-line divisions, like prose texts. Some manuscripts (e.g., the Junius MS) systematically mark the divisions with a certain punctuation.

This use of the asterisk differs from its use in historical linguistics where the asterisk denotes that the form is not recorded but is a probable reconstruction. The two uses, however, agree in showing that the form marked with the symbol is not attested.

In Beowulf, on the other hand, the inflected (manuscript) form has sometimes been changed to the uninflected form for the sake of metre. See Bliss (1967: 44) and Fulk, Bjork, and Niles (2008: 3289, 21).

Kiernan, however, admits non-alliterating lines as intelligent variation rather than scribal corruption (1996: 185). Niles (1994) also regards the manuscript reading handgripe as preferable since it indicates a rough and ready quality in the poets artistry that reveals itself in an indifference to alliterative norms even when these norms could easily be satisfied (1994: 4578).

For the editorial readings of Beo 1546a, see the apparatus criticus of Fulk, Bjork, and Niles (2008: 53). Niles follows the manuscript, stating that [t]he rule that a verse requires a minimum of four syllables is a modern one, and there is no way to test for a consciousness of it on the part of Anglo-Saxon poets (1994: 459).

According to Bliss (1962: 14), the two sounds [velar and palatal g] alliterate freely together until about the year 1000.

In cynne, c remained unpalatalized /k/ because y resulted from i-umlaut (cf. Gmc *kunjam).

In Beowulf, ondlean requital and ondslyht counterblow, both of which alliterate with vowels, are always spelled with initial h- in the manuscript (cf. ll. 1541, 2094, 2929, 2972).

The usage of the terms crossed alliteration (sometimes cross alliteration) and transverse alliteration varies among scholars; Lehmann and Tabusa (1958) and Le Page (1959) use crossed alliteration for both types; Cassidy and Ringler (1971) employs transverse alliteration as an umbrella term; Baker (2007) calls [AB: AB] transverse alliteration and [AB: BA] crossed alliteration.

Creed (1993) discusses the use of linked alliteration (enjambed alliteration in his term) in Beowulf.

See Russom (1987: 71). Donoghue (1990: 71), however, finds Russoms tree-based analysis problematic because the first lift of the off-verse, which has often been regarded as metrically most prominent, is governed by a weak node. From the viewpoint of verse composition, however, it would be more natural that the first lift of the on-verse linearly preceding that of the off-verse be a determining factor in alliteration. See Fujiwara (1990: 231).

Pope-Fulk (2001) use the term Rule of Precedence for our Left Dominance.

The classification into stress-words, particles, and proclitics is roughly based on that made by Kuhn (1933).

Pope (1966) and Bliss (1967) prefer the scansion with stress on un-.

, some scholars do not allow rising feet.

Type D2 in our notation is called Type D4 by Sievers, who reserves Types D2 and D3 for minor variants of Type D1.

Sievers (1885, 1893).

See Stanley (1974, 1992) and Donoghue (2006).

Russom (2002a: 315) questions rhythmic stress on the short medial syllable of Class II weak verbs.

Bliss (1967) scans this verse as Type E (3E2 in his notation).

Cable (1972) merges Type D2 into Type E to simplify Sieverss five types.

If analysed as Type E, however, this verse is an exceptional form where the first lift is immediately followed by an unstressed syllable. Cassidy and Ringler think that the weak syllable ending in n is easily slurred in the rhythm (1971: 286).

Mald 11b, 32b, 55b, 72b, etc.

In Beowulf, there occur nine possible instances of Type E with anacrusis (501b, 662a, 932b, 949b, 1236a, 1329b, 1830b, 1941b, 2441a). Bliss, however, takes them as Type B since disyllabic anacrusis is exceedingly rare, and trisyllabic anacrusis unparalleled (1967: 50).

Bliss (1967: 46).

See also Beo 25b, 112b, 386b, 528b, 629b, 820a, 1036b, 1180a (resolved), 1264b, 1883a, 2034b, 2054b.

First proposed by Sievers (1885: 232, 312).

Sedgefield (3rd ed., 1935), Pope (1966: 320, 372), Fulk (1992: 205, 276), and Fulk, Bjork, and Niles (2008: 174).

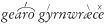

More precisely, if the ending of a resolvable sequence is historically long, resolution is blocked. Thus, in  ready for the revenge for injury (Beo 2118a), -wrce does not undergo resolution because the genitive singular ending -e of the o-stem feminine noun originates in Proto-Germanic -z and is historically long.

ready for the revenge for injury (Beo 2118a), -wrce does not undergo resolution because the genitive singular ending -e of the o-stem feminine noun originates in Proto-Germanic -z and is historically long.

See Kaluza (1909), Pope (1966), Bliss (1967), Nakagawa (1982), and Russom (1987), among others.

Suzuki (1996a: 14958).

As noted in the preface, the poets choice (or avoidance) of certain metrical patterns is not considered to be a deliberate act but an intuitive process.

McIntosh (1949: 120).

The line is quoted from Cassidy and Ringler (1971: 243).

Mald 14, 83, 235, 272; DAlf 21; JDay II 83; LPr II 100; MCharm 11 42.

This is not the case with and wa. Besides the unique instance in Beowulf (955a), there are some sixty instances of wa (particularly in the Paris Psalter), many of which, unlike other adverbs in -a such as gna and geta, occur in verses where the use of the shorter form would be metrically possible.

GenA 2248, 2652; And 422, 475; GuthA 155, 233, 446; GuthB 1270; Rid 40 58; PPs 93.13.1; Sol II 250.

Beo 51b, 245a, 255a, 568b, 1013b, 1346a, 1355a, 1798a, 1945a, 2022b, 2895a, 3113b.

Bliss (1967: Appendix C, Table II). See also Hutcheson (1995: 198203).

Kendall (1991: 246) classifies this verse as Type C (C in his notation) without placing rhythmic stress on the finite verb secga. Under this analysis, the use of the longer slende would still cause metrical difficulty because the verse-final dip of Type C never consists of more than one unstressed syllable (

Next page

ready for the revenge for injury (Beo 2118a), -wrce does not undergo resolution because the genitive singular ending -e of the o-stem feminine noun originates in Proto-Germanic -z and is historically long.

ready for the revenge for injury (Beo 2118a), -wrce does not undergo resolution because the genitive singular ending -e of the o-stem feminine noun originates in Proto-Germanic -z and is historically long.