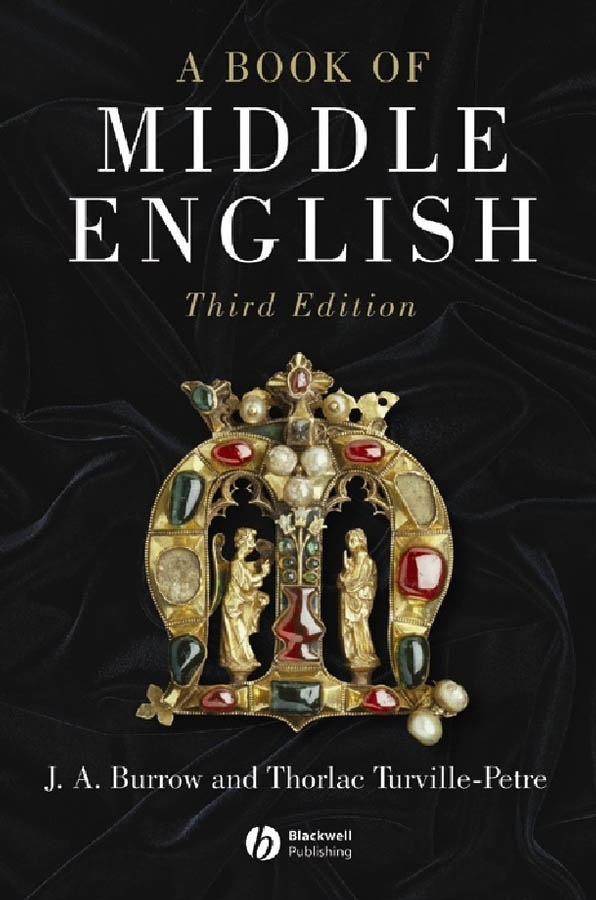

1992,1996, 2005 by J. A. Burrow and Thorlac Turville-Petre

BLACKWELL PUBLISHING

350 Main Street, Maiden, MA 02148-5020, USA

9600 Garsington Road, Oxford OX4 2DQ, UK

550 Swanston Street, Carlton, Victoria 3053, Australia

The right of J. A. Burrow and Thorlac Turville-Petre to be identified as the Authors of this Work has been asserted in accordance with the UK Copyright, Designs, and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, except as permitted by the UK Copyright, Designs, and Patents Act 1988, without the prior permission of the publisher.

First published 1992

Second edition published 1996

Third edition published 2005 by Blackwell Publishing Ltd

4 2007

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Burrow, J. A. (John Anthony)

A book of Middle English / J. A. Burrow and Thorlac Turville-Petre3rd ed.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references

ISBN: 978-1-4051-1708-1 (alk. paper) - ISBN: 978-1-4051-1709-8 (pbk)

1. English languageMiddle English, 11001500Grammar.

2. English languageMiddle English, 11001500Readers. 3. English literature

Middle English, 11001500. I. Turville-Petre, Thorlac. II. Title.

PE.535.B87 2004

427'.02dc22

2004047627

A catalogue record for this title is available from the British Library.

The publishers policy is to use permanent paper from mills that operate a sustainable forestry policy, and which has been manufactured from pulp processed using acid-free and elementary chlorine-free practices. Furthermore, the publisher ensures that the text paper and cover board used have met acceptable environmental accreditation standards.

For further information on

Blackwell Publishing, visit our website:

www.blackwellpublishing.com

List of Illustrations

The dialects of Middle English

Dot maps of THEM: th- type and h- type

Lines from St Erkenwald (MS Harley 2250)

A page from Confessio Amantis (MS Fairfax 3)

Clerkes knowe wel ynow at no synfol man do so wel at he ne

my te do betre, noer make so good a translacyon at

te do betre, noer make so good a translacyon at

he ne my te make a betre.

te make a betre.

Treisa

Preface to the Third Edition

This book is a companion to Mitchell and Robinsons Guide to Old English. It contains representative pieces of English writing from the period c.1150c.1400. We have included examples of romance, battle poetry, chronicle, biblical narrative, debate, dialogue, dream vision, religious and mystical prose, miracle story, fabliau, lyric poetry and drama. Although the choice of pieces has been determined by literary considerations, the general introduction concentrates on matters of language. We have attempted, in this introduction, to give readers only such information about the language as we consider essential for the proper understanding and appreciation of the texts. Since these texts exhibit many varieties of Middle English, from different periods and regions, our account is inevitably selective and somewhat simplified. For further reading on the language, and also on the history and literature of the period, the reader is referred to the Bibliography.

The headnote to each text provides a brief introduction, together with a short reading list. Annotations and Glossary are both quite full; but, for reasons of space, explanations given in notes at the foot of the page are not duplicated in the Glossary.

The third edition has been revised throughout. It includes two new texts: 10 Pearl ll. 1480, and 17 Chaucers Troilus and Criseyde Book II ll. 1497.

Our debts to earlier editors will be evident throughout. We are particularly grateful to Ronald Waldron for allowing us to use his work on the Trevisa (text 12). Hanneke Wirtjes kindly read Part One and suggested improvements. We received advice from the Custodian of Berkeley Castle, Richard Beadle, Alison McHardy, Jeremy Smith, Michael Smith, Myra Stokes, and Anthony Tuck. For help with the etymological entries in the Glossary we owe a great debt to David A. H. Evans. We are also grateful to the libraries which granted us access to their manuscripts, to Aberdeen University Press for permission to reproduce the maps on p. 16, to the many colleagues who responded to the questionnaire originally sent out by the publishers, and to several reviewers and correspondents who suggested improvements. We are indebted again to Margaret Aherne for her meticulous work on this new edition.

J.A.B., T.T.-P.

Abbreviations

| AV | Authorized Version of the Bible |

| Bede, History | Bedes Ecclesiastical History of the English People, ed. Bertram Colgrave and R. A. B. Mynors (Oxford, 1969) |

| Chaucer | References are to The Riverside Chaucer, ed. Larry D. Benson (Boston, 1987; Oxford, 1988) |

| EETS | Early English Text Society (e.s. = extra series) |

| Guide to Old English | Bruce Mitchell and Fred C. Robinson, A Guide to Old English (6th edn, Oxford, 2001) |

| Linguistic Atlas | A. McIntosh, M. L. Samuels and M. Benskin, A Linguistic Atlas of Late Mediaeval English (Aberdeen, 1986) |

| ME | Middle English |

| MED | Middle English Dictionary |

| OE | Old English |

| OED | Oxford English Dictionary |

| ON | Old Norse |

| PL | Patrologia Latina, ed. J.-P. Migne |

| Trevisa, Properties | On the Properties of Things. John Trevisas Translation of Bartholomus Anglicus De Proprietatibus Rerum (Oxford, 1975) |

| Vulgate | References are to the Douai translation of the Latin Vulgate Bible (see 12/92n.) |

| Whiting | B. J. Whiting and H. W. Whiting, Proverbs, Sentences, and Proverbial Phrases from English Writings Mainly Before 1500 (Cambridge, Mass., 1968) |

Abbreviations of grammatical terms are listed in the Headnote to the Glossary.

Part One

1

Introducing Middle English

1.1 THE PERIOD

The term Middle English has its origins in nineteenth-century studies of the history of the English language. German philologists then divided the history into three main periods: Old (alt-), Middle (mittel-), and New or Modern (neu-). Middle English is commonly held to begin about 110050 and end about 14501500. Unlike periods in political history, many of which can be dated quite precisely if need be (by a change of monarch or dynasty or regime), linguistic periods can be defined only loosely. Languages change all the time in all their aspects vocabulary, pronunciation, grammatical forms, syntax, etc. and it is impossible to decide exactly when such changes add up to something worth calling a new period. Yet, for all this lack of precision, it seems clear that the language of a mid-twelfth-century writing such as our extract from the

Next page

te do betre, noer make so good a translacyon at

te do betre, noer make so good a translacyon at