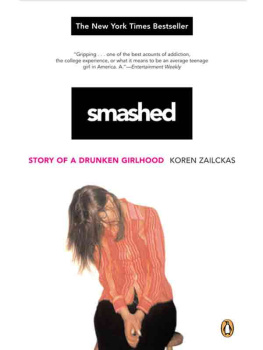

PENGUIN BOOKS

Published by the Penguin Group

Penguin Group (USA) Inc., 375 Hudson Street, New York, New York 10014, U.S.A.

Penguin Group (Canada), 90 Eglinton Avenue East, Suite 700, Toronto,

Ontario, Canada M4P 2Y3 (a division of Pearson Penguin Canada Inc.)

Penguin Books Ltd, 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, England

Penguin Ireland, 25 St Stephens Green, Dublin 2, Ireland (a division of Penguin Books Ltd)

Penguin Group (Australia), 250 Camberwell Road, Camberwell,

Victoria 3124, Australia (a division of Pearson Australia Group Pty Ltd)

Penguin Books India Pvt Ltd, 11 Community Centre, Panchsheel Park,

New Delhi110 017, India

Penguin Group (NZ), cnr Airborne and Rosedale Roads, Albany, Auckland 1310, New Zealand (a division of Pearson New Zealand Ltd)

Penguin Books (South Africa) (Pty) Ltd, 24 Sturdee Avenue,

Rosebank, Johannesburg 2196, South Africa

Penguin Books Ltd, Registered Offices:

80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, England

First published in the United States of America by Viking Penguin, a member of Penguin Group (USA) Inc. 2005

Published in Penguin Books 2006

Copyright Koren Zailckas, 2005

All rights reserved

the library of congress has catalogued the hardcover edition as follows:

Zailckas, Koren.

Smashed : story of a drunken girlhood / Koren Zailckas.

p. cm.

ISBN: 978-1-1011-9139-2

Designed by Carla Bolte Set in Granjon

Except in the United States of America, this book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, resold, hired out, or otherwise circulated without the publisher's prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

The scanning, uploading and distribution of this book via the Internet or via any other means without the permission of the publisher is illegal and punishable by law. Please purchase only authorized electronic editions, and do not participate in or encourage electronic piracy of copyrighted materials. Your support of the author's rights is appreciated.

Making or distributing electronic copies of this book constitutes copyright infringement and could subject the infringer to criminal and civil liability.

www.penguin.com

For my mother,

who first made me mindful of womens issues

T HIS IS THE kind of night that leaves a mark. When I surface, its events and the shame of them will be gone from my head, cut away as though by some surgical procedure. I will not miss the memories that were carved out of me: when my father carried me in his arms through the sliding glass doors, my head lolling the way it used to when I was the little girl whom he carried to bed. When a friend, being interviewed by the doctor treating me, had to answer vodka, which is like a curse word, in the fact that we exploit it in private but dont dare utter it in the presence of adults. When a row of people looked up from their laps because the scene of a girl, dead-drunk at sixteen, momentarily distracted them from their midnight emergencies.

I wont remember the chair that wheels me down the hospitals hall, or the white cot I am lain on, or the tube that coasts through my esophagus like a snake into a crawl space. Yet I will retain these lost hours, just as my forearms will hold the singes of strangers cigarettes in coming years, as my back will hold the scratch of a spear-point fence, as my fingers will hold griddle scars from a nonstick grill. This is the first of many forgotten injuries that will imprint me just the same.

When I surface, there wont be any spells of shivering or gut purling, any percussion between my temples. I wont need to follow the doctors orders: Tylenol for discomfort. There will be no physical discomfort. My body will be still and indifferent, but mentally, the soreness of the overdose will linger.

Its strange the way the mind remembers forgetting. The fact of the blackout wont slip away like the events that took place inside of it. Instead of receding into my lifes story, the lost hours will stand out. Something else will move in to fill in the holes: dread and denial that thickens with time like emotional scar tissue. In the absence of memory, the night will be even more memorable. The blackout will stay with me, causing chronic, psychic pain, a persistent, subconscious thrumming.

M Y INTENTION , in telling this story from the very beginning, is to show the full life cycle of alcohol abuse. I did not begin by drinking from steep glasses, viscous concoctions of rum, gin, vodka, and triple sec, and I did not start off blacking out or vomiting blood. Like most abiding behaviors, my drinking was an evolution that became desperate over time: I found alcohol during my formative years. I warmed to it instantly. Like a childhood friend, it aged with me.

I grew up in the Northeast, a white, middle-class teenager among other white, middle-class teenagers, which plunks me down in one of the highest demographics of underage drinkers. I am also Catholic, a faith that some researchers find increases the odds that teenagersparticularly girlswill drink, and drink savagely.

I started drinking before I started high school. I had my first sips of whiskey not more than a year after I first went to a gymnasium dance or first dragged a disposable razor over one knee, balancing myself on the edge of the bathtub. I had just burgeoned the new breasts I needed to shop for blouses in the juniors department. I had only just crammed my blinking dolls and seam-split stuffed animals into a box in the attic.

I drank throughout high school, but not every weekend, not even every other weekend. It was the promise of drinking that sustained me through all of high schools afflictions: the PSATs and the SATs, report cards and driving tests, and presidential fitness exams.

In high school, I sought out booze the way boys my age sought out sex. At parties, I leered when girls unzipped their backpacks, hoping to catch the glint of a bottle; and my own sly glances reminded me of the boys who leered when girls bent forward, hoping to glimpse their breasts through the necks of their blouses. The brief encounters fed me. For weeks, Id relive swilling rum in a graffitied bathroom stall during a Battle of the Bands, vodka in the wooded perimeters outside of a football game, tequila at a sleepover after somebodys mom fitted a nightlight into the wall and announced she was going to bed.

I drank through college, too, with an appetite that had me drinking rum by the half-liter bottle, until I couldnt squelch the impulse to unload my secrets to strangers, or sob, or pass out wherever I happened to be standing. I drank until Id forgotten how much I had already drunk, and then I drank more.

For four years, I drank aimlessly when I might have been doing things that were far more gratifying. I might have been forming real friendships, the kind that would have stretched into adulthood, and had me in ill-fitting bridesmaid dresses at half a dozen best friends weddings. I might have been writing stories or taking pictures. I might have been sleeping a full six hours a night, or eating three square meals a day, or taking multivitamins. I might have been learning the language of affection: how to exchange glances or trace a mans fingertips with mine. I might have been reading the top hundred books of all time.

I drank after college. I drank through my first real move, my first job as an executive assistant, my first insurance forms, my first tax filing, and my first apartment where rent was due on the first of the month. I drank after the real world revealed itself to me like a magic trick, after I saw the method of adulthood, the morning commutes and mindless jobs, which shattered the illusions I had about it.