Contents

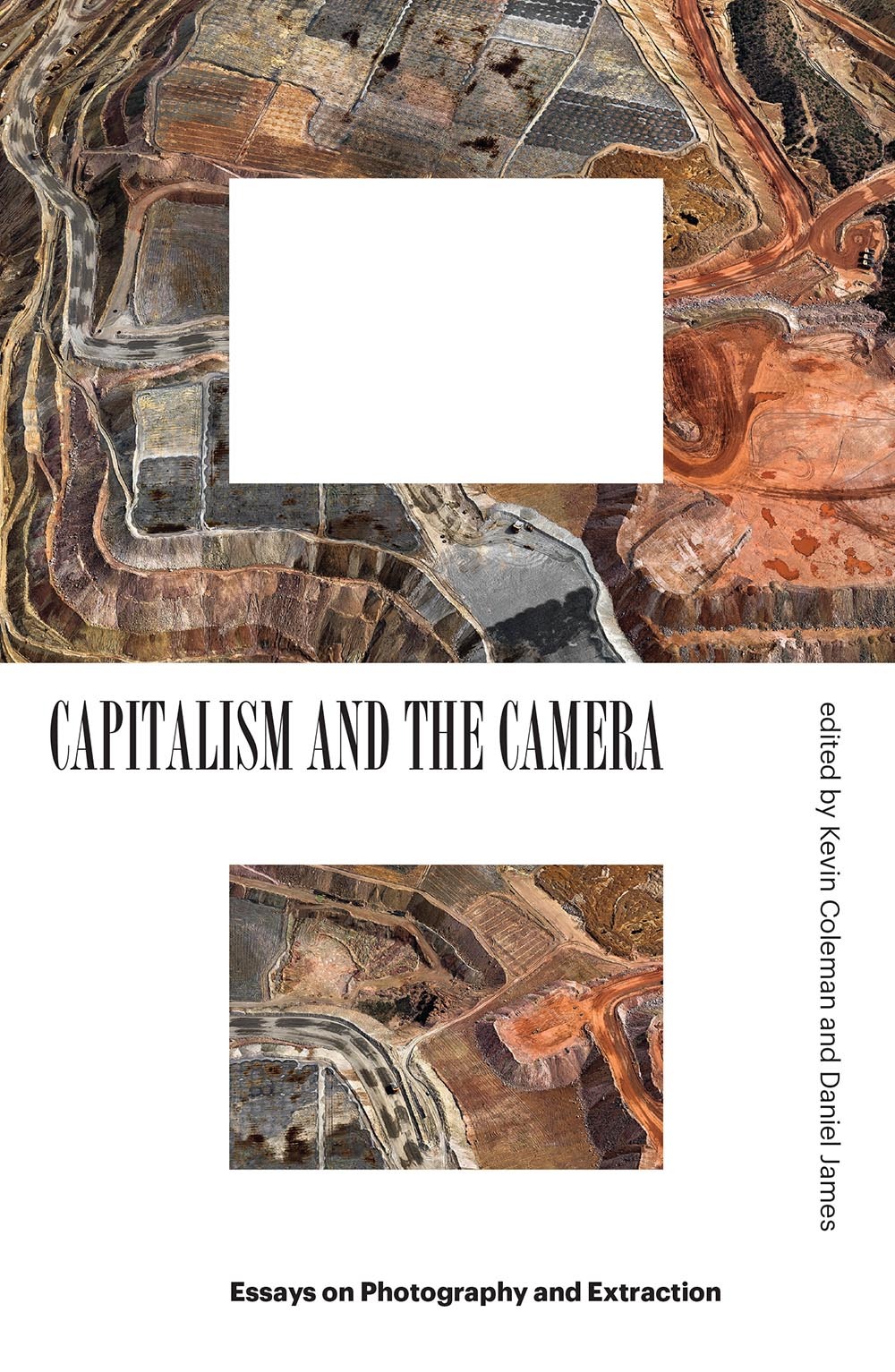

Capitalism and the Camera

Capitalism and the Camera

Essays on Photography and Extraction

Edited by Kevin Coleman

and Daniel James

First published by Verso 2021

Collection Verso 2021

Contributions Contributors 2021

All rights reserved

The moral rights of the editors and authors have been asserted

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

Verso

UK: 6 Meard Street, London W1F 0EG

US: 20 Jay Street, Suite 1010, Brooklyn, NY 11201

versobooks.com

Verso is the imprint of New Left Books

ISBN-13: 978-1-83976-080-8

ISBN-13: 978-1-83976-081-5 (UK EBK)

ISBN-13: 978-1-83976-082-2 (US EBK)

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

A catalog record for this book is available from the Library of Congress

Typeset in Sabon by MJ & N Gavan, Truro, Cornwall

Printed and bound by CPI Group (UK) Ltd, Croydon CR0 4YY

Contents

1. Capitalism and the Camera

Kevin Coleman and Daniel James

2. Toward the Abolition of Photographys Imperial Rights

Ariella Asha Azoulay

3. Mining the History of Photography

Siobhan Angus

4. Go Away Closer: Photography, Intermediality, Unevenness

Kajri Jain

5. Anti-Capitalism and the Camera

Walter Benn Michaels

6. Capitalism without Images

T. J. Clark

7. Moths to the Flame: Photography and Extinction

John Paul Ricco

8. Public Photography

Blake Stimson

9. Marketing the Socialist Experiment: Soviet Photo-Reportage between the World Wars

Christopher Stolarski

10. Where There Is No Room for Fiction: Urban Demolition and the Politics of Looking in Postsocialist China

Tong Lam

11. The Mirror and the Mine: Photography in the Abyss of Labor

Jacob Emery

Plate Section

Embedded Figures

The histories of capitalism and photography are also histories of financing and logistics. At the University of Toronto in September 2017 and May 2018, we brought some of the leading scholars of photography into conversation with key scholars of capitalism. We thank the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada for funding this project through a Connections grant that enabled us to convene these workshops. We also thank the various programs within the University of Toronto that supported this initiative: Office of the Dean, the Department of Historical Studies, the Department of History, the Department of Visual Studies, and the Latin American Studies program. Thanks also to the Bernardo Mendel Research Fund at Indiana University. Our two two-day meetings were intense. Through debate and discussion, we clarified significant conceptual, methodological, and political differences.

Our biggest thanks are reserved for the participants in these workshops: Siobhan Angus, Ariella Azoulay, Jennifer Bajorek, Joaqun Barriendos Rodrguez, Elspeth Brown, Tina Campt, Jill Casid, Zahid Chaudhary, William Fysh, Liliana Gmez-Popescu, Dan Guadagnolo, Kajri Jain, Rachel Johnston Hurst, Tong Lam, Walter Benn Michaels, Nicholas Mirzoeff, Dara Orenstein, John Paul Ricco, Nicols Sillitti, Blake Stimson, Christopher Stolarski, Olivia Tait, Erica Toffoli, Alberto Toscano, and Laura Wexler. And although they could not participate in the workshops, T. J. Clark, Jacob Emery, and Mirta Zaida Lobato have supported this project in meaningful ways. On the ground, we could not have pulled off these meetings without the support and assistance of Rebecca Wittmann, Nick Terpstra, Andreas Bendlin, Duncan Hill, Shabina Moheebulla, Heather Thornton, Sharon Marjadsingh, Susan Antebi, Alison Syme, and Phub Dorji. We are grateful to Nicholas Brown, who read through the entire manuscript and generously offered us a critical outsiders perspective on it. Finally, our hearty thanks to Jessie Kindig at Verso, for helping to shape this book and for brilliantly engaging with our arguments.

Capitalism and

the Camera

Kevin Coleman and

Daniel James

Photography was invented in the years between the publication of Adam Smiths The Wealth of Nations (1776) and Karl Marx and Friedrich Engelss The Communist Manifesto (1848). The emergence of philosophical-historical accounts of the division of labor, primitive accumulation, and commodity fetishism, on the one hand, and of a practical, mechanical method for fixing images, on the other, is significant. One was a branch of thought that named a new object of analysis, the economy (a combination of the Greek oikos, household, and nomos, law), and the other a branch of popular mechanics and chemistry that sought (to use the terms of the day) to arrest nature by making copies that she herself appeared to trace without the clumsy intervention of a human hand (the writing with light that is photo-graphy ). Beyond this twinned birth of technologies of reproduction in the age of empire, what are the connections between capitalist accumulation and photography? And might photography play a role in refusing capitals infringements upon human freedom and planetary life? These two questions are the basis for this book.

Just before the invention of the economy and photography, another term was created: fossil fuel. Once again, light played a crucial role. The idea that ancient photosynthesis produced energy that various organismstrees, plants, dinosaursrelied upon as sources for their own development was first put forth in 1597, about a century after Europeans initiated the plunder and pathogenetic destruction of the Indigenous communities of the Americas. By 1759, a German chemist named Caspar Neumann used the term fossil fuel. Coal, petroleum, natural gasformed millions of years ago from the remains of dead organismsare the source of 85 percent of todays global energy consumption.

Loss of species, the acidification of the oceans, extreme heat and massive flooding, the melting of the polar ice caps: each of these impacts of global warming has dramatically accelerated since the 1992 publication of the United Nations Climate Change Framework. Capitalism is generating these crises.

In just our lifetimes, the burning of fossil fuels and the (seemingly unrelated) increase in the circulation of images have proceeded at breakneck pace. Since World War II, a portion of humanity has released about 85 percent of the carbon that is trapped in the atmosphere. More than half of those emissions have taken place since 1989. The ecological cost of capitalism is clear.

There have been social costs as well. The historic dispossession of Indigenous peoples, the enslavement of Africans, and

In the face of this concatenation of crises, each caught in overlapping feedback loops that distribute their effects into putatively separate domains, one might legitimately wonder what this has to do with the camera. Capitalist consumption is a key factor driving global warming. The circulation of images, in turn, drives consumption. The desire to have a certain way of life is curiously first an image and only second a reality. I see, therefore I desire. At the same time, activists and artists use photography and video to produce images that serve as evidence or abstractions that might nudge various publics into changing their behavior or demanding change from their state.