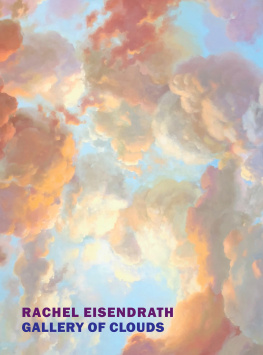

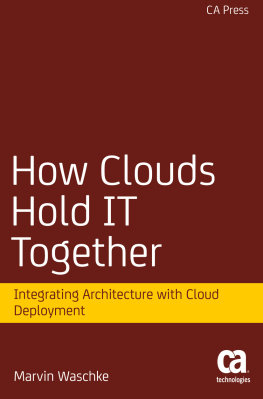

Gallery of Clouds

RACHEL EISENDRATH

New York Review Books

New York

This is a New York Review Book

published by The New York Review of Books

435 Hudson Street, New York, NY 10014

www.nyrb.com

Copyright 2021 by Rachel Eisendrath

All rights reserved.

Cover image: James Wall Finn, Mural for the Rose Reading Room, New York Public Library; photograph Robert R. Lowe, III / Appitecture.net.

Cover design: Katy Homans

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Eisendrath, Rachel, author.

Title: Gallery of clouds / Rachel Eisendrath.

Description: New York City : New York Review Books, 2021.

Identifiers: LCCN 2020016141 (print) | LCCN 2020016142 (ebook) | ISBN 9781681375434 (hardcover) | ISBN 9781681375441 (ebook)

Subjects: CSH: Books and reading. | LiteratureAppreciation.

Classification: LCC Z1003 . E355 2021 (print) | LCC Z1003 (ebook) | DDC 028/.9dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020016141

LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020016142

ISBN 978-1-68137-544-1

v1.0

For a complete list of titles, visit www.nyrb.com or write to:

Catalog Requests, NYRB, 435 Hudson Street, New York, NY 10014

an and-then structure (or nonstructure). These books are long, therefore, not in order to complete any discernible trajectory or arc, nor to create an illusion of completeness, but rather to make you feel that the adventures could go on forever, that there is no intrinsic reason why these books should ever have to stop, and that, as Borges also says, even after these books have ended at some more or less arbitrary spot, you will feel that they are still, somewhere, going on. Like the Arabian Nights or In Search of Lost Time, these books do not fight off death; rather, they forestall it. They do so by increasing the thickness of time, which maybe also means that they are sometimes a little boringin a luxuriant way. Their air is thicker than air; it is golden and sun-drenched and heavy. I will get up and do what I am supposed to do, these books say, but not quite yet.

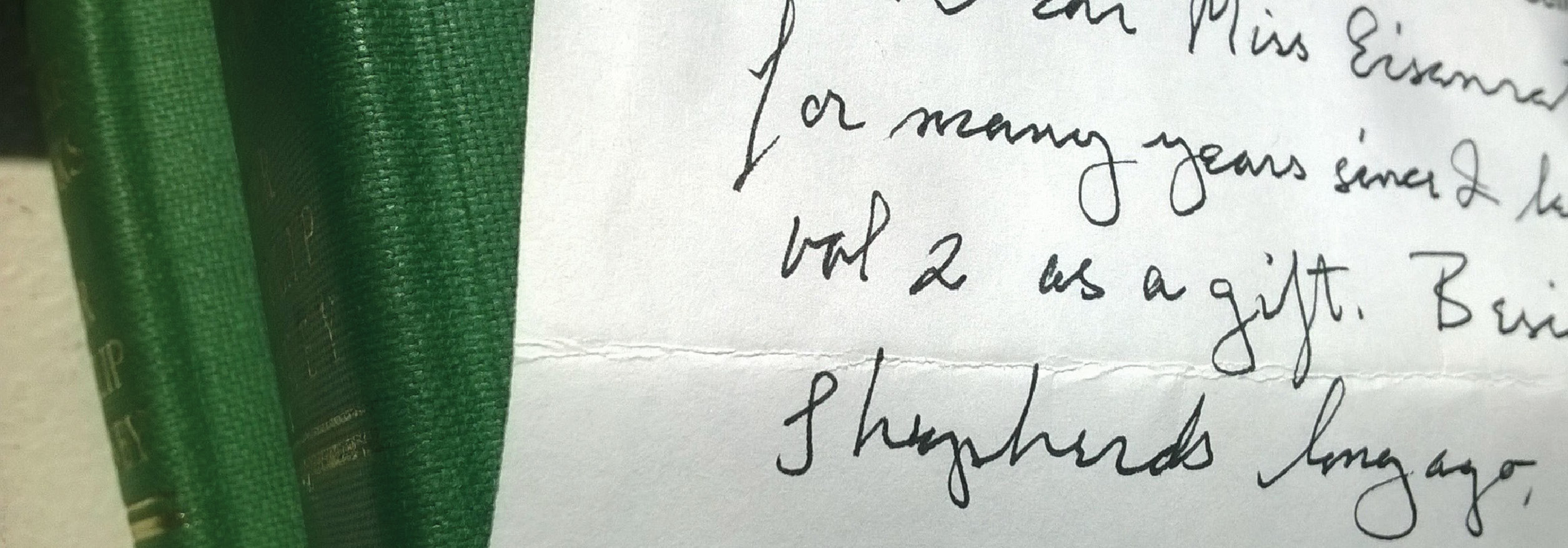

In this particular case, I had ordered only one volume, but two green hardback books, their spines slightly faded from sunlight, had arrived in the mail: volumes I and II of a 1963 Cambridge reprint of Albert Feuillerats 1912 edition of The Prose Works of Sir Philip Sidney. The spines of the volumes were stiff and softly cracked when I opened them. Unfolding the package, I found this note from the seller inside:

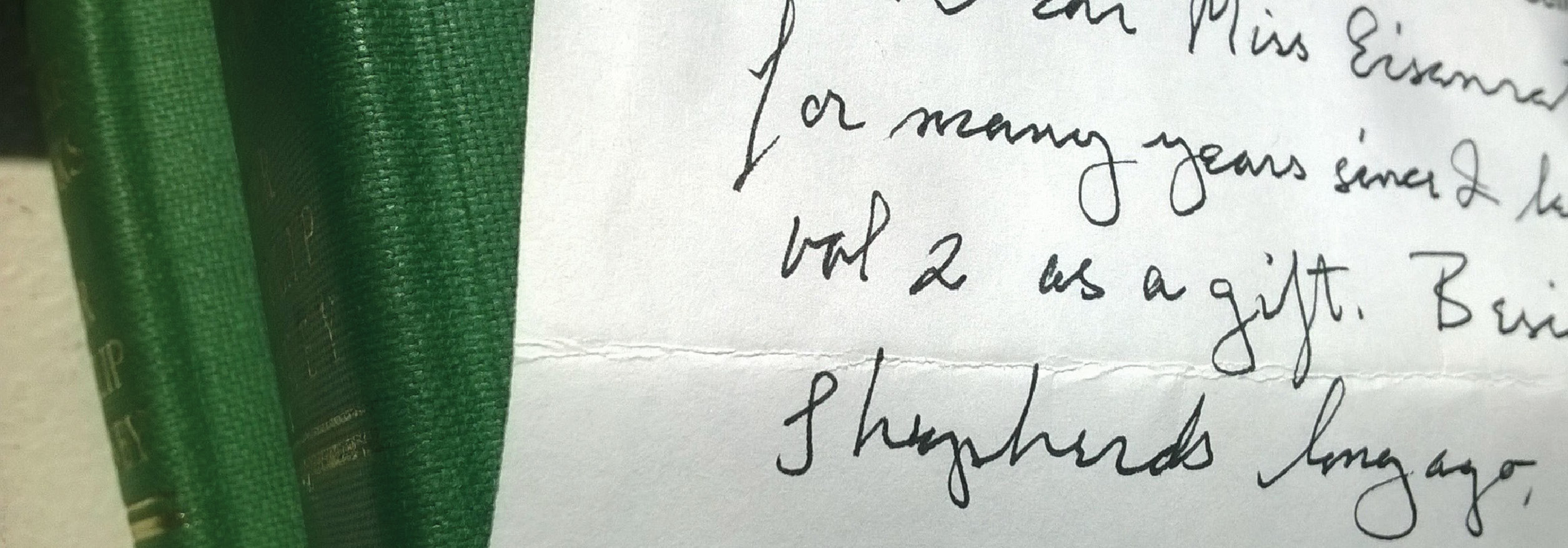

Dear Miss Eisendrath,

These books have stood side by side for many years since I left graduate school. Please accept vol 2 as a gift. Besides, I left the land of nymphs and shepherds long ago.

R.C.W

The script was a wavering cursive, from the generation of my grandmothers; the last sentence was written in iambic heptameter. The note evoked not only the geographical distance of the previous owner but also the gap of time: a period in graduate school many years ago, and then untold years on the shelf during which these two volumes had stood together as witness to the slow unfolding of their previous readers life. Now he was no longer young, and these same volumes lay in my hands. It was as if the books were not just about romance, but had themselves come from the world of romance. as if by their own weight: We like to feel, she writes, that the present is not all; that other hands have been before us, smoothing the leather until the corners are rounded and blunt, turning the pages until they are yellow and dogs-eared. We like to summon before us the ghosts of those old readers who have read their Arcadia from this very copy. The Arcadia has a peculiar power to produce such conditions of readership: the book starts to seem like some object from within its own pages, a wondrous object that has its own sprawling story to tell of distant places and long-ago times and hard travel.

A teacher of mine had once made such books attractive to me not by bringing them close and making them seem modern, but, with wistful love and rigor, by holding them at a distancewhere they had gleamed darkly like someone elses jewels.  He had once been mocked for arguing that the place of fairyland in Edmund Spensers 1590 The Faerie Queeneanother English cousinwas real: it was, he said, for so Spenser had said. Fairyland was the New World, a real place that in the late sixteenth century still glowed in the half-light of European longing. But if my teacher was mocked, what did he care? He spent his days bent over old maps and manuscripts in his sixteenth-floor apartment in Chicago. It was said that he had two apartments: one to hold books; the other, next door, to hold books and a bed. Poised over Lake Michigan, with the city sprawled beneath him, his apartment might as well have been the peak of Machu Picchu. He seemed to me to be a character of romance himself. Imagine erudition illuminated by wonder. He would travel to the places he wrote about: for his book on trade and romance, he had journeyed in bits and pieces along much of the Silk Road. Once, he sent me one of my chapter drafts with his comments from a hotel in the Alps of Switzerland, where, he said, the staff always saved a particular room for him each year. I wondered at the brown envelope, which bore the handwriting of the concierge, as I would have a rock from the moon or a ring of the sultan. It was this teacher who told me that the most amazing magic that the fantastical pages of romance produce is this: that the real is what is to be wondered at.

He had once been mocked for arguing that the place of fairyland in Edmund Spensers 1590 The Faerie Queeneanother English cousinwas real: it was, he said, for so Spenser had said. Fairyland was the New World, a real place that in the late sixteenth century still glowed in the half-light of European longing. But if my teacher was mocked, what did he care? He spent his days bent over old maps and manuscripts in his sixteenth-floor apartment in Chicago. It was said that he had two apartments: one to hold books; the other, next door, to hold books and a bed. Poised over Lake Michigan, with the city sprawled beneath him, his apartment might as well have been the peak of Machu Picchu. He seemed to me to be a character of romance himself. Imagine erudition illuminated by wonder. He would travel to the places he wrote about: for his book on trade and romance, he had journeyed in bits and pieces along much of the Silk Road. Once, he sent me one of my chapter drafts with his comments from a hotel in the Alps of Switzerland, where, he said, the staff always saved a particular room for him each year. I wondered at the brown envelope, which bore the handwriting of the concierge, as I would have a rock from the moon or a ring of the sultan. It was this teacher who told me that the most amazing magic that the fantastical pages of romance produce is this: that the real is what is to be wondered at.

In the case of Sidneys Arcadia, the book writes such conditions of wonder-filled reading into its own pages. Sidney describes in the opening dedication the circumstance of his very first reader, his sister, the Countess of Pembroke, for whom he composed the romance:

it is not, being but a trifle, and that triflingly handled. Your dear self can best witness the manner, being done in loose sheets of paper, most of it in your presence, the rest, by sheets, sent unto you, as fast as they were done. In sum, a young head, not so well stayed as I would it were (and shall be when God will), having many fancies begotten in it, if it had not been in some way delivered, would have grown a monster, & more sorry might I be that they came in, than that they got out.

Conjured before us: loose sheets of paper that Sidney handed to his sister one after the other, the ink still wet, as soon as he had composed themalmost like letters written from the land of his imagination, while the events he fantasized were just then unfolding in his mind.

This condition of domestic familiarity and knowing humor endowed with humanity the rhetorically elaborate arabesques of Sidneys pen. I imagine that he and his sister must have wondered at themselves, as my family wondered at itself living such a different kind of life in a one-bedroom apartment in Washington, DC, turning to themselves as objects of fantasy that were also real:

He had once been mocked for arguing that the place of fairyland in Edmund Spensers 1590 The Faerie Queeneanother English cousinwas real: it was, he said, for so Spenser had said. Fairyland was the New World, a real place that in the late sixteenth century still glowed in the half-light of European longing. But if my teacher was mocked, what did he care? He spent his days bent over old maps and manuscripts in his sixteenth-floor apartment in Chicago. It was said that he had two apartments: one to hold books; the other, next door, to hold books and a bed. Poised over Lake Michigan, with the city sprawled beneath him, his apartment might as well have been the peak of Machu Picchu. He seemed to me to be a character of romance himself. Imagine erudition illuminated by wonder. He would travel to the places he wrote about: for his book on trade and romance, he had journeyed in bits and pieces along much of the Silk Road. Once, he sent me one of my chapter drafts with his comments from a hotel in the Alps of Switzerland, where, he said, the staff always saved a particular room for him each year. I wondered at the brown envelope, which bore the handwriting of the concierge, as I would have a rock from the moon or a ring of the sultan. It was this teacher who told me that the most amazing magic that the fantastical pages of romance produce is this: that the real is what is to be wondered at.

He had once been mocked for arguing that the place of fairyland in Edmund Spensers 1590 The Faerie Queeneanother English cousinwas real: it was, he said, for so Spenser had said. Fairyland was the New World, a real place that in the late sixteenth century still glowed in the half-light of European longing. But if my teacher was mocked, what did he care? He spent his days bent over old maps and manuscripts in his sixteenth-floor apartment in Chicago. It was said that he had two apartments: one to hold books; the other, next door, to hold books and a bed. Poised over Lake Michigan, with the city sprawled beneath him, his apartment might as well have been the peak of Machu Picchu. He seemed to me to be a character of romance himself. Imagine erudition illuminated by wonder. He would travel to the places he wrote about: for his book on trade and romance, he had journeyed in bits and pieces along much of the Silk Road. Once, he sent me one of my chapter drafts with his comments from a hotel in the Alps of Switzerland, where, he said, the staff always saved a particular room for him each year. I wondered at the brown envelope, which bore the handwriting of the concierge, as I would have a rock from the moon or a ring of the sultan. It was this teacher who told me that the most amazing magic that the fantastical pages of romance produce is this: that the real is what is to be wondered at.