CLOUDS

The Earth series traces the historical significance and cultural history of natural phenomena. Written by experts who are passionate about their subject, titles in the series bring together science, art, literature, mythology, religion and popular culture, exploring and explaining the planet we inhabit in new and exciting ways.

Series editor: Daniel Allen

In the same series

Air Peter Adey

Cave Ralph Crane and Lisa Fletcher

Clouds Richard Hamblyn

Desert Roslynn D. Haynes

Earthquake Andrew Robinson

Fire Stephen J. Pyne

Flood John Withington

Gold Rebecca Zorach and Michael W. Phillips Jr

Islands Stephen A. Royle

Lightning Derek M. Elsom

Meteorite Maria Golia

Moon Edgar Williams

Mountain Veronica della Dora

Silver Lindsay Shen

South Pole Elizabeth Leane

Storm John Withington

Tsunami Richard Hamblyn

Volcano James Hamilton

Water Veronica Strang

Waterfall Brian J. Hudson

Clouds

Richard Hamblyn

REAKTION BOOKS

Published by Reaktion Books Ltd

Unit 32, Waterside

4448 Wharf Road

London N1 7UX, UK

www.reaktionbooks.co.uk

First published 2017

Copyright Richard Hamblyn 2017

All rights reserved

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publishers

Page References in the Photo Acknowledgements and

Index match the printed edition of this book.

Printed and bound in China

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

eISBN: 9781780237701

CONTENTS

The wind was all bangs, howls, rattles. A tropical storm.

Introduction: Airy Nothings

I look about; and should the guide I choose

Be nothing better than a wandering cloud,

I cannot miss my way.

William Wordsworth, The Prelude, Book One

When the playwright Aristophanes set out to satirize the state of fifth-century Athenian philosophy, he cast a chorus of clouds as the source of the airy thinking that was the principal target of his scorn. They nourish the brains of the whole tribe of sophists, as the Socrates of his dark comedy The Clouds (c. 420 BC) declares. They are the celestial Clouds, the patron goddesses of the layabout. From them come our intelligence, our dialectic and our reason; also, our speculative genius and all our argumentative talents. The trouble with sophists and poets and other such dirty long-haired weirdies, he complains, is that they were always talking about clouds and things:

Thats right, isnt it? Deadly lightning, twisted bracelet of the watery Clouds and Locks of the hundred-headed Typhon and Conflagrating storms and Airy nothings and Crook-talond birds, the swimmers of the air and let me think yes! Showers of moisture from the dewy Clouds. Thats right!

But then philosophers have always had their heads in the clouds, their thought processes variously characterized as cloudy, woolly, airy, vague, nebulous, foggy, or lost in clouds of theory. While overly complex thinking serves to cloud the issue, wrong-headed thinking leads you into Aristophaness cloud cuckoo land. But while clouds are ready metaphors for muddle and uncertainty the cloud of unknowing, the fog of war They confound the senses and trouble the mind; for Ren Descartes, in his essay, On Meteors (1637), clouds constitute the most extreme manifestation of the ungraspable, so if you can philosophize about clouds, he argued, you can philosophize about anything:

Nicolas Poussin, Blind Orion Searching for the Rising Sun, late 1650s, oil on canvas. The huntress Diana (goddess of the moon) is shown standing upon the grey clouds that wreathe Orions face, literally clouding his vision.

Since one must turn his eyes toward heaven to look at them, we think of them as being so high that even poets and

Clouds, in other words, should be brought down to earth, their varied movements accounted for and thereby rendered unmysterious. But clouds have always been more than merely meteorological, possessing rich cultural and emotional associations that extend far beyond their fleeting atmospheric lives. When the sixth-century mountain hermit and Daoist scholar Tao Hongjing declined his emperors invitation to serve in the court at Liang, China, he invoked the incommunicability of clouds as a symbol of his distance from the emperors materialist world:

What is there in the mountains?

Over the ranges there are copious white clouds

But I can only enjoy them by myself

And am unable to offer them as a gift to you.

A circumzenithal arc (also known as a cloud smile) is an optical phenomenon caused by the refraction of light through ice crystals present in thin cirriform clouds. Because ice crystals refract sunlight more effectively than water droplets, the colours of a circumzenithal arc are often brighter and more intense than those of a rainbow. |

|

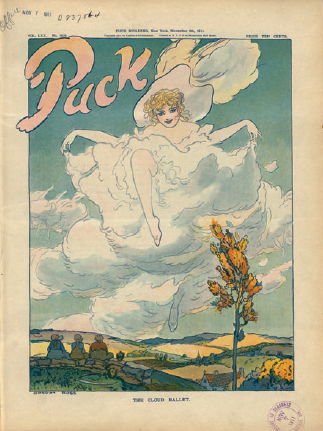

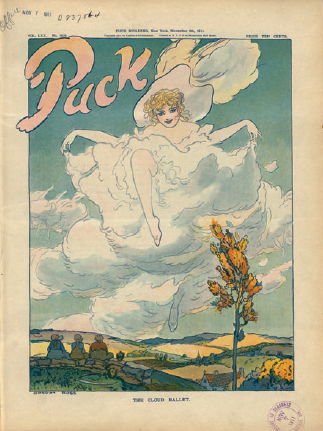

| Cloud fantasia: a ballerina glimpsed in the clouds, from Puck magazine, 1911. |

For Tao, the clouds represent freedom, purity and immateriality. They are an affirmation of the contemplative life, a towering and wonderful foreign land above our heads, in the words of the German philosopher Ernst Bloch, who invoked the imaginative lure of the ultimate wish-landscape above, a fairy-tale realm where there are castles, too, taller than they are on earth.

Clouds have been objects of delight and fascination throughout human history, their fleeting magnificence and endless variability providing food for thought for scientists and daydreamers alike. As this book sets out to show, life without clouds would be physically unendurable alongside their rain-bearing function, clouds act as a finely tuned planetary thermostat while it would also be mentally and spiritually bereft, depriving us of a limitless source of creative contemplation. Clouds are thoughts without words, as the Canadian poet Clouds, like thoughts, are thus inherently unreliable but, as the following chapter will argue, they are also an endlessly mutable, magical screen onto which dreams, ideas, myths and legends have always been projected.

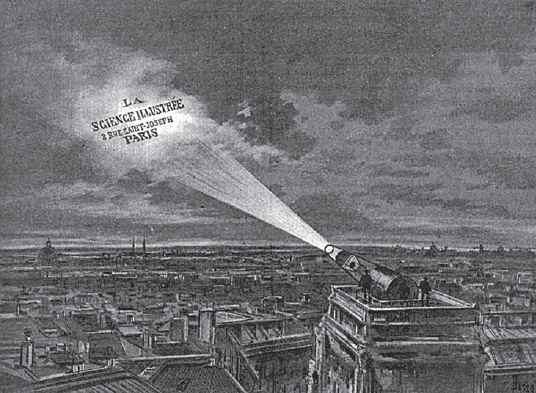

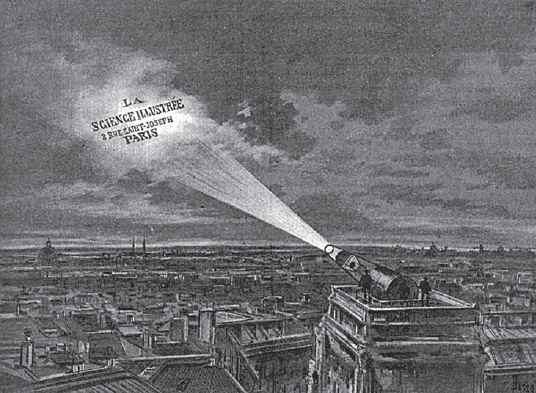

Clouds as an aerial projector screen: a promotional illustration from La Science illustre (1894).

1 Clouds in Myth and Metaphor

Tell me, Alvis! Youre the dwarf who knows everything about our fates and fortunes: what is the name for the clouds, that hold the rain, in each and every world?