The weather is a very British obsession. In fact, Id say thats an understatement. The great British weather, as its known to many in this country, is part of the fabric of our nation a natural force that binds us together. Whether its too hot, too cold, too wet, or too windy, even in the middle of a heatwave the weather breaks the ice in conversations.

As the striking photographs in this book attest, the weather in all its guises equally fascinates people around the world. From the simple act of raising an umbrella, to an aircraft that changes course to avoid a thunderstorm, every day the weather touches all our lives. I know many readers share my interest in the weather, as the ever-growing band of dedicated observers and amateur forecasters shows. But such is my passion for the weather Ive made it my career. Over the course of nearly 30 years at the Met Office the UKs national weather service Ive been captivated by the weathers power and beauty. Through forecasting, Ive come to understand better its whims and to appreciate the magic I see day by day just by looking up at the sky.

Today, of course, all of us wherever we are, face the challenge of climate change, which is already bringing more extreme weather, more frequently to parts of the world. But whenever the weather makes its presence felt, we at the Met Office have an eye on the sky: from advising the British public on whether to expect rain as the occasional drop, drizzle or downpour, through to briefing multinational corporations on what the future climate may bring. To me, all weather is extraordinary for its ability to unite people of all ages and walks of life, even when its raining cats and dogs.

INTRODUCTION

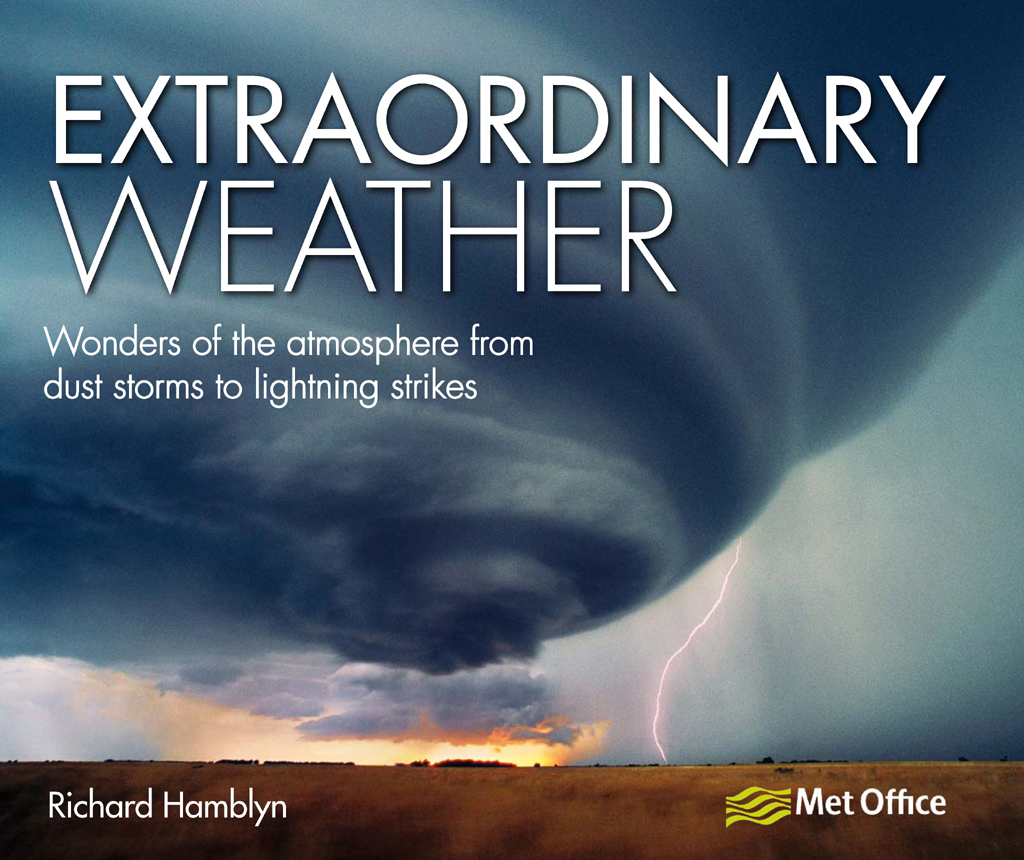

The wayward beauty of our atmosphere flows from its essential dynamism, from the fact that there is never a moment when nothing can be said to be happening. At any one time, more than a thousand thunderstorms are in progress around the world, their restless summits rising towards the stratosphere, 10km (6 miles) or more above the Earth. Somewhere right now a tornado will be spinning, lightning crackling across the sky, and hail clattering on to roofs; elsewhere a dust storm will be advancing across a desert while, somewhere else, the weight of rime ice will be bringing down a power line. Meanwhile, perhaps, someone on the other side of the world will be photographing a miraculous sunset.

The sky is the ultimate art gallery above, as Ralph Waldo Emerson famously remarked an open-air gallery that is perpetually rearranging its displays, from the great summer spectaculars of lightning and hailstones to the quieter, more contemplative visions of rainbows, haloes and crepuscular rays, all of which, and much else besides, can be found in the six themed chapters of this book: Storms and Tempests; Ice and Snow; Heat and Drought; Atmospherics; Strange Phenomena; and Man-made Weather.

Extraordinary Weather has been written with the view that all types of weather are extraordinary, but some are more extraordinary than others. Take the eerie display of mammatus clouds on page 121, for example, which loom towards Earth as though part of some imminent alien invasion, or the double trouble storm image on page 31, in which a waterspout and a lightning strike make a brief elemental combination. These images seem so strange and otherworldly, and have such intense dramatic appeal, that it is easy to forget that, astonishing as they are, the events they depict are thoroughly normal. Indeed none of the weather moments that feature in this book could be categorized as freakish or supernatural at all which is not to say that all of them are natural. As was the case with my earlier collection, Extraordinary Clouds (2009), one of the most eye-opening sections of this book is the one devoted to the subject of man-made weather, from artificially triggered lightning to contrails and ship tracks: this is a category of weather that has become increasingly prevalent in recent years, and will go on to be more prevalent in the future.

We have known for some time that human activity is altering the climate, but to what extent is it altering the weather? This is a complex question to which no adequate answers can yet be given, but we can certainly look at the cloud layer above densely populated regions and see that aircraft contrails are now among the most abundant cloud types on the planet (see ).

But it is not just the look of our skies that is changing. In May 2011, the charity Oxfam published a report entitled Times Bitter Flood, which pointed to the fact that while the frequency of geophysical events such as earthquakes and volcanic eruptions has remained more or less constant over recent years, disasters associated with flooding and storms have risen from around 130 a year in the 1980s to more than 350 a year today: an increase of more than 4 per cent per year. In 2011 alone, there were record-breaking floods in Australia (where, in the countrys worst natural disaster, an area the size of Germany and France remained inundated for two months), Brazil (which also experienced the worst floods in its history) and the American state of Missouri, where large sections of the Missouri River burst its banks following record snowfall in the Rocky Mountains along with near-record rainfall in Montana. A record-breaking year for tornadoes, meanwhile, saw more than 1,700 in the United States alone, one of which, on May 22, 2011, killed 159 people in the city of Joplin, Missouri. In Mexico, the worst wildfires in the countrys history coincided with an April heatwave that saw temperatures peak at 48.8C (119.8F), while an unprecedented dry spell over western Europe saw wildfires breaking out in areas as unlikely as Ireland and the Highlands of Scotland. Journalists around the world took to describing this catalogue of unruly weather as global weirding, but the reality is that deeper snowfalls, more widespread flooding, heavier rains and greater extremes of heat and cold now constitute the new normal, and are inescapable features of the ongoing climatic reconfiguration to which the world must learn to adapt.

Earths atmosphere is of course a globally circulating system, but because most of us experience it on a local level, it is hard to imagine our day-to-day weather as part of a wider picture. Satellite imagery offers a powerful corrective to this, which is why each chapter of this book includes a number of satellite pictures that allow us to zoom out from an individual weather event to show it in its fuller context. The cloud shadows image on page 83 is an instructive example, for not only does it demonstrate the mechanism of crepuscular ray formation, it also shows how their radial appearance is a trick of linear perspective, since from this altitude the shadows can be seen to be parallel. It is one of my favourite images in the book, not least because it reminds us that we cannot rely on first impressions when it comes to the turbulent world of weather, where things are not always what they seem. Turn, for instance, to the picture on page 110. Is it a fish? Is it a dragon? No, its just an unusual side effect of the physics of cloud convection, but, in common with most of the other images I have chosen for this book, it has a powerful, if transient, ambiguity. Welcome to the world of extraordinary weather!