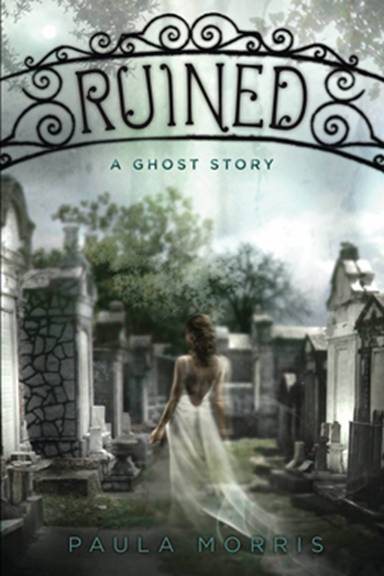

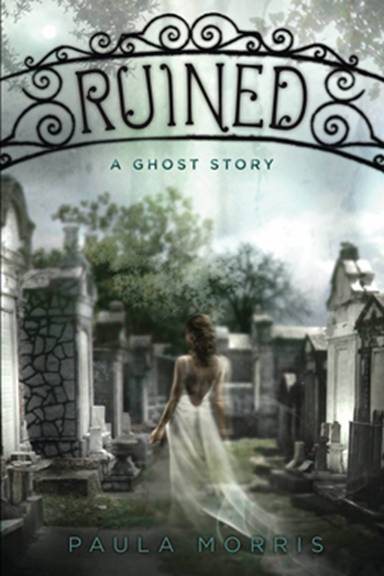

Ruined

Paula Morris

FOR REBECCA HILL

PROLOGUE

New Orleans, the summer of l853- Yellow fever ravages the busyport city. Bells toll for the souls of the dead. Boats on the Mississippi Riverare placed in quarantine, their cargoes left to spoil, their crews felled bydisease. Before the summer is over, eight thousand people will die.

In the city, yellow fever is known as the Stranger's Disease.Immigrants -- Italian, Greek, German, Polish, new arrivals from the greatcities of New York and Boston -- have no resistance to the fever. The Irish,who'd traveled to New Orleans to escape their terrible famine, soon fallvictim, dying within a week of the first sinister chill.

During the day, the streets are empty. At night, mass burials takeplace all over town. Graveyards fill; corpses lie rotting in piles, swelling inthe sun. Gravediggers are bribed with alcohol to ignore the putrid smell anddig shallow trenches for the bodies of the poor. New Orleans's black population-- slaves and the free people of color -- have seemed largely immune, but inAugust of l853, even they start to succumb. Native-born wealthy families --Creole and American -- suffer as badly as poor immigrants.

The ornate tombs in the walled cemeteries, New Orleans's famousCities of the Dead, fill with mothers and fathers, daughters and sons. AtLafayette Cemetery, on the new,

American side of the city, bodies are left at the gates everynight. There is no room to bury these unknown dead, and many of the corpses areburned.

In the last week of August, in the dead of night, a group of menunlock the Sixth Street gates to Lafayette Cemetery and make their way bytorchlight to an imposing family tomb. Two coffins of yellow fever victims,both from the same family, had been placed in the vault earlier that afternoon,one on each of its long, narrow shelves. According to local custom, once inplace, the coffins should have been sealed behind a brick wall for a year and aday.

But the coffins are still unsealed. The men remove the marbleplate, covering their mouths, choking at the smell of the bodies decomposing inthe heat. Onto the top coffin, they slide a shrouded corpse, then quicklyreplace the plate.

The next day, the tomb is sealed. A year later, the men return tobreak through the bricks. The two disintegrating coffins are thrown away, and thebones of the dead covered with soil in the caveau, a pit at the bottomof the vault.

The names of the first two corpses interred in the vault thatterrible August are carved onto the tomb's roll call of the dead. The name ofthe third corpse is not.

Only the men who placed the body inside the tomb know of itsexistence.

***

CHAPTER ONE

***

TORRENTIAL RAIN WAS POURING THE AFTER" noon Rebecca Brownarrived in New Orleans. When the plane descended through gray clouds, she couldonly glimpse the dense swamps to the west of the city. Stubby cypress treespoked out of watery groves, half submerged by the rain-whipped waters, fleckedwith snowy herons. The city was surrounded by water on all sides -- by swampsand bayous; by the brackish Lake Pontchartrain, where pelicans swooped and anarrow causeway, the longest bridge in the world, connected the city with itsdistant North Shore; and, of course, by the curving Mississippi River, heldback by grass-covered levees.

Like many New Yorkers, Rebecca knew very little about New Orleans.She'd barely even heard of the place until Hurricane Katrina hit, when it wason the news every night -- and it wasn't the kind of news that made anyone wantto move there. The city had been decimated by floodwaters, filling up like abowl after the canal levees broke. Three years later, New Orleans still seemedlike a city in ruins.

Thousands of its citizens were still living in other parts of thecountry. Many of its houses were still waiting to be gutted and rebuilt; manyhad been demolished. Some of them were still clogged with sodden furniture andcollapsed roofs, too dangerous to enter, waiting for owners or tenants whonever came back.

Some people said the city -- one of the oldest in America -- wouldnever recover from this hurricane and the surging water that followed. Itshould be abandoned and left to return to swampland, another floodplain for themighty Mississippi.

"I've never heard anything so ridiculous in my life,"said Rebecca's father, who got agitated, almost angry, whenever an opinion ofthis kind was expressed on a TV news channel. "It's one of the greatAmerican cities. Nobody ever talks about abandoning Florida, and they gethurricanes there all the time."

"Tail's is the only great city in America," Rebecca toldhim. Her father might roll his eyes, but he wouldn't argue with her: There wasnothing to argue about. New York was pretty much the center of the universe, asfar as she was concerned.

But now here she was -- flying into New Orleans one month beforeThanksgiving. A place she'd never been before, though her father had an oldfriend here -- some lady called Claudia Vernier who had a daughter, Aurelia.Rebecca had met them exactly once in her life, in their room at a Midtownhotel. And now she'd been taken out of school five weeks before the end of thesemester and sent hundreds of miles from home.

Not for some random, impromptu vacation: Rebecca was expected to livehere. For six whole months.

The plane bumped down through the sparse clouds, Rebecca scowlingat her own vague reflection in the window. Her olive-toned skin lookedwinter-pale in this strange light, her mess of dark hair framing a narrow faceand what her father referred to as a "determined" chin. In New Yorkthe fall had been amazing: From her bedroom window, Central Park looked onfire, almost, ablaze with the vivid colors of the dying leaves. Here,everything on the ground looked dank, dull, and green.

Rebecca wasn't trying to be difficult. She understood that someoneneeded to look after her: Her father -- who was a high-powered tech consultant-- had to spend months in China on business, and she was fifteen, too young tobe left alone in the apartment on Central Park West. Usually when he wastraveling for work, Mrs. Horowitz came to stay. She was a nice elderly lady wholiked watching the Channel II news on TV with the volume turned up too loud,and who got irrationally worried about Rebecca eating fruit at night and takingshowers instead of baths.

But no. It was too long for Mrs. Horowitz to stay, her fathersaid. He was sending her to New Orleans, somewhere that still looked like a warzone. On TV three years ago they'd seen the National Guard driving around inarmored vehicles. Some neighborhoods had been completely washed away.

"The storm was a long time ago -- and anyway, you're going tobe living in the Garden District," he had told her. They were sitting inher bedroom, and he was picking at the

frayed edges of her cream-colored quilt, not meeting Rebecca'seye. "Everything's OK there -- it didn't flood. It's still a beautiful oldneighborhood."

"But I don't even know Aunt Claudia!" Rebecca protested."She's not even my real aunt!"

"She's a very good friend of ours," her father said, hisvoice strained and tense. "I know you haven't seen her for a long time,but you'll get on just fine with her and Aurelia."

All Rebecca could remember of Aunt Claudia were the janglybracelets she had worn and her intense green eyes. She'd been friendly enough,but Rebecca had been shooed away after a couple of minutes so the adults couldtalk. She and Aurelia, who was just a little girl then, seven years old andvery cute, spent the rest of the visit playing with Aurelia's dolls in thehotel bedroom.

And these were the people -- these

Next page