Halal

If You

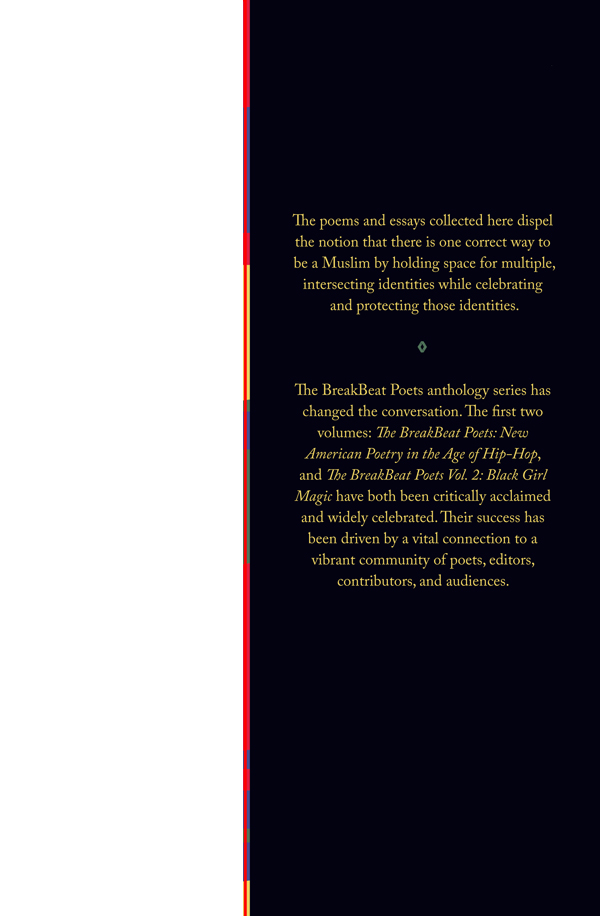

Hear Me The Breakbeat Poets Series About the BreakBeat Poets series The BreakBeat Poets series, curated by Kevin Coval and Nate Marshall, is committed to work that brings the aesthetic of hip-hop practice to the page. These books are a cipher for the fresh, with an eye always to the next. We strive to center and showcase some of the most exciting voices in literature, art, and culture. BreakBeat Poets series titles include:

The BreakBeat Poets: New American Poetry in the Age of Hip-Hop, edited by Kevin Coval, Quraysh Ali Lansana, and Nate Marshall

This Is Modern Art: A Play, Idris Goodwin and Kevin Coval

The BreakBeat Poets Vol 2: Black Girl Magic, edited by Mahogany L. Browne, Jamila Woods, and Idrissa Simmonds

Human Highlight, Idris Goodwin and Kevin Coval

On My Way to Liberation, H. 3 Halal

If You

Hear

Me

Edited by Fatimah Asghar and Safia Elhillo

Haymarket Books

Chicago, Illinois 2019 Fatimah Asghar and Safia Elhillo Published in 2019 by Haymarket Books P.O. 3 Halal

If You

Hear

Me

Edited by Fatimah Asghar and Safia Elhillo

Haymarket Books

Chicago, Illinois 2019 Fatimah Asghar and Safia Elhillo Published in 2019 by Haymarket Books P.O.

Box 180165 Chicago, IL 60618 773-583-7884 www.haymarketbooks.org ISBN: 978-1-60846-606-1 Distributed to the trade in the US through Consortium Book Sales and Distribution (www.cbsd.com) and internationally through Ingram Publisher Services International (www.ingramcontent.com). This book was published with the generous support of Lannan Foundation and Wallace Action Fund. Special discounts are available for bulk purchases by organizations and institutions. Please call 773-583-7884 or email for more information. Cover artwork, Disco Baby, by Ayqa Khan. Cover design by Brett Neiman.

Printed in Canada by union labor. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication data is available. 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1  Safia Elhillo Foreword: Good Muslim / Bad Muslim I didnt have a Muslim community growing up because I was afraid. White people were mostly an abstraction for me as a child, and so was their judgementa question about my accent here, a comment about my body hair there. They didnt know, early on, specific enough ways to really hurt me. The ones with that particular toolkit were my own people.

Safia Elhillo Foreword: Good Muslim / Bad Muslim I didnt have a Muslim community growing up because I was afraid. White people were mostly an abstraction for me as a child, and so was their judgementa question about my accent here, a comment about my body hair there. They didnt know, early on, specific enough ways to really hurt me. The ones with that particular toolkit were my own people.

A comment at Sudanese Sunday school about how I wore such tight jeans because I didnt have a father at home. Whispers about my divorced mother. My hair was this. My complexion was that. My Arabic, too this, too that. My family was this.

I was too new, then too Americanized. I memorized their voices, anticipated their critique. This T-shirt was too short and revealed the roll of fat above my hips. This one was too tight and cupped my nonexistent breasts. I was a child, reallythere was no reason for anyone to be looking at my body that way. But I would pull on a pair of jeans and anticipate eyes on the curve they made of my lower half.

The way they molded to my ass. Or didnt. I spent most of my early adolescence swimming in fabrica gray fleece Gap sweater that I wore every day, boys cargo pants, oversize souvenir T-shirts my mother brought me from her travels. My own secular kind of covering. I didnt want anyone to look at me, to say anything. As an adult, now with plenty of trauma at the hands of white people, the judgement I still fear the most is by those meant to be my people.

I screenshot horrible things Muslim men say to me on the Internet, and read and reread their messages into the night. I read and reread the comment left on a photo of mine, by a man I do not know, telling me in Arabic that my nose ring does not look good on me. The comment is so small, probably typed in passing. It takes over my entire day. I eventually delete it, but still cannot stop talking about it, months later. I have spent, really, my whole adult life and most of my adolescence, most of my childhood, trying to avoid being talked about in any capacity.

People will talk was a governing principle in my upbringing, in my culturea way of letting me know I should not do something (cut my hair short, wear clothes that are too tight, wear clothes that are too loose, be photographed with men, curse on the Internet, talk about my body, pierce my nose, double-pierce my ears, wear my hair in its natural curls to a wedding, wear a hoop nose ring), without giving the direct instruction. Ive been afraid, forever, of performing my identity incorrectly. My Muslimness, my Sudaneseness, my Americanness, my Blackness, my womanhood, all of it. I was a solitary kid, introverted and always reading, painfully shy. I looked to books to teach me how people were with each otherhow they talked, how they touched, how they played, how they trusted, how they mourned. I practiced alone at nightjokes, pronunciations, nicknames I wanted people to give me.

Tools of American girlhood like playing with my hair and keeping things in the back pocket of my jeans. I wasnt in any of the books I was readingmaybe a sliver here or there, a character with brown skin, with parents from somewhere else, with curly hair, but never the full extent of my intersection. I also wasnt seeing anyone ever talk about the nuances available in Muslim identityat least not for women. I grew up watching men I knew drink and smoke and go to mosque, all in the same day. Their Muslimness felt like it made room for everything in their lives. The women I knew were not at all afforded this nuancethey were regarded either as religious or as secular.

There was nothing in between. So I grew up hearing and using terms like bad Muslim and good Muslim and thinking of them as fixed identities. My first semester of college, I was scared and overstimulated and homesick and sad, and did not pray for months. And so I thought I was a bad Muslim, and thinking of myself as a bad Muslim allowed more months to pass without prayer, because praying started to feel like something I didnt deserve to do. I mourned my good Muslimness. I felt my whole life growing increasingly opaque outside to how Muslim I felt inside.

I didnt have anyone to talk to about it. Id meet new people who didnt know for months that I was Muslim. Id meet other Muslims and obsess later about what they were saying about the fact that Id been wearing shorts. I was very lonely. The poems and essays in this anthology are the Muslim community I didnt know I was allowed to dream of. The Muslim community in which my child-self could have blossomedproof of the fact that there are as many ways to be Muslim as there are Muslims.

That my way was one of those ways, was a way of being Muslim that did count. The writers in this anthology demonstrate the sheer cacophony of Muslimness, of Muslim identities, of Muslim people. The range of things were allowed to say and feel and want and mourn and joke about. Were accustomed, at this point, to media in which a cis, straight Muslim man gets to express his flawed Muslimness, to mess up and stray away and return and sin and repent and everything else that humans do. But the cisness, the straightness, the maleness of these voices has kept them safe in their expression of their flaws, in their trying to find their unique place within Islam. There are no stones for their bodies, no disownings, no honor killings.

Haymarket Books

Haymarket Books Safia Elhillo Foreword: Good Muslim / Bad Muslim I didnt have a Muslim community growing up because I was afraid. White people were mostly an abstraction for me as a child, and so was their judgementa question about my accent here, a comment about my body hair there. They didnt know, early on, specific enough ways to really hurt me. The ones with that particular toolkit were my own people.

Safia Elhillo Foreword: Good Muslim / Bad Muslim I didnt have a Muslim community growing up because I was afraid. White people were mostly an abstraction for me as a child, and so was their judgementa question about my accent here, a comment about my body hair there. They didnt know, early on, specific enough ways to really hurt me. The ones with that particular toolkit were my own people.