The BreakBeat Poets Volume 2

The BreakBeat Poets Volume 2

Edited by

Mahogany L. Browne

Idrissa Simmonds

Jamila Woods

2018 Mahogany L. Browne, Idrissa Simmonds, and Jamila Woods

Published in 2018 by

Haymarket Books

P.O. Box 180165

Chicago, IL 60618

773-583-7884

www.haymarketbooks.org

ISBN: 978-1-60846-870-6

Trade distribution:

In the US, Consortium Book Sales and Distribution, www.cbsd.com

In Canada, Publishers Group Canada, www.pgcbooks.ca

In the UK, Turnaround Publisher Services, www.turnaround-uk.com

All other countries, Ingram Publisher Services International,

This book was published with the generous support of Lannan Foundation and Wallace Action Fund.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication data is available.

Cover art, Chocolate Lady by Brianna McCarthy.

Cover design by Brett Neiman.

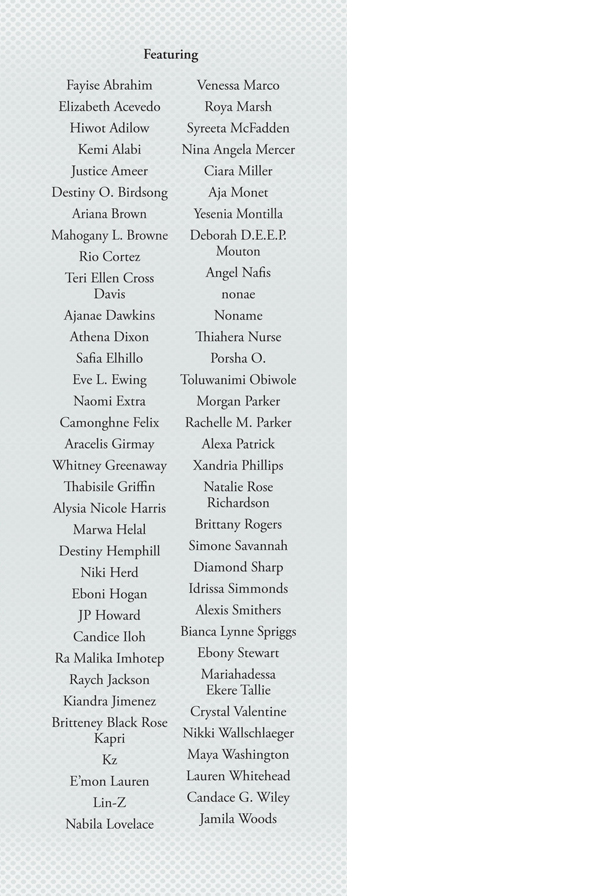

Index of Poets

Fayise Abrahim,

Elizabeth Acevedo,

Hiwot Adilow,

Kemi Alabi,

Justice Ameer,

Destiny O. Birdsong,

Ariana Brown,

Mahogany L. Browne,

Rio Cortez,

Teri Ellen Cross Davis,

Ajanae Dawkins,

Athena Dixon,

Safia Elhillo,

Eve L. Ewing,

Naomi Extra,

Camonghne Felix,

Aracelis Girmay,

Whitney Greenaway,

Thabisile Griffin,

Alysia Nicole Harris,

Marwa Helal,

Destiny Hemphill,

Niki Herd,

Eboni Hogan,

JP Howard,

Candice Iloh,

Ra Malika Imhotep,

Raych Jackson,

Britteney Black Rose Kapri,

Kiandra Jimenez,

Kz,

Emon Lauren,

Lin-Z,

Nabila Lovelace,

Venessa Marco,

Roya Marsh,

Syreeta McFadden,

Nina Angela Mercer,

Ciara Miller,

Aja Monet,

Yesenia Montilla,

Deborah D.E.E.P. Mouton,

Angel Nafis,

nonae,

Noname,

Thiahera Nurse,

Porsha O.,

Toluwanimi Obiwole,

Morgan Parker,

Rachelle M. Parker,

Alexa Patrick,

Xandria Phillips,

Natalie Rose Richardson,

Brittany Rogers,

Simone Savannah,

Diamond Sharp,

Idrissa Simmonds,

Patricia Smith,

Alexis Smithers,

Bianca Lynne Spriggs,

Ebony Stewart,

Mariahadessa Ekere Tallie,

Crystal Valentine,

Nikki Wallschlaeger,

Maya Washington,

Lauren Whitehead,

Candace G. Wiley,

Jamila Woods,

Foreword

Patricia Smith

Almost thirty years ago, I wrote a poem that stumbled toward explaining my unsteady root in the world. I was weary of scratching out life under a microscope, of having that life dissected, defined, and ultimately dismissed by others. When I sat down to scrawl this thick stanza, with its single capital letter and breathless progression, I was both fed up with explaining and desperately craving an explanation.

What Its Like to Be a Black Girl (For Those Of You Who Arent)

First of all, its being 9 years old and

feeling like youre not finished, like your

edges are wild, like theres something,

everything, wrong. its dropping food

coloring in your eyes to make them blue and suffering

their burn in silence. its popping a bleached

white mop head over the kinks of your hair and

priming in front of the mirrors that deny your

reflection. its finding a space between your

legs, a disturbance in your chest, and not knowing

what to do with the whistles. its jumping

double dutch until your legs pop, its sweat

and vaseline and bullets, its growing tall and

wearing a lot of white, its smelling blood in

your breakfast, its learning to say fuck with

grace but learning to fuck without it, its

flame and fists and life according to motown,

its finally having a man reach out for you

then caving in

around his fingers.

At nine, all I craved to be was other. I prayed that blue-black, nappy and female was a temporary malady, that the West Side of Chicago was just a training ground for the wider worldthe world presented as a dreamily whitewashed dreamscape that I never doubted represented a reality just outside my reach.

Even my mother, my guidance, urged me to crave who I wasnt. As an answer to Who am I, really? I was plopped down in front of our big floor model Philco to watch a succession of television shows featuring several hundred carefully framed lives I was urged to aspire to. When my mother was done cackling at the goofiness of Lucille Ball or professing Walter Cronkite a god of sorts, I flipped channels. I flipped channels, searching American faces, listening to American conversations, peeking into American homes. Of course, I never found a Black girl.

No voices sounded like mine, so every plummet and rise in my song was wrong somehow. No faces looked like mine, and I despised the mirror for its inability to utter the lies I needed to hear. In the world I was being taught was the right one, no streets, no neighborhoods, no schools, no mothers looked anything like mine.

So I turned away from the babbling broadcasts and began to wait. I waited patiently for a peculiar and impossible magic, that sweep of the wand that would lift me from the baffling throes of little Black girl-dom and into the righteous, much easier existence awaiting me.

Meanwhile, my nose was too broad, my hair too crinkled. I clutched shameful stories of a mother from Alabama, a daddy from Arkansas, and their loud way with double negatives. I lived in a tenement hovel where roaches dropped from the ceiling into my bed and mice got trapped inside the stove. That hovel happened to be on the West Side of Chicago, the side of town everybody warned you to stay away from. And the school was one of the worst in the city. And, from the woman purporting to be my rock: For Jesus sake, girl, talk right like you got some sense. If you ever want to get out of this neighborhood, ever, you got to fix your tongue and talk right, like white people, you got to talk about stuff white folks talk about, you got to say things white folks want to hear. And Lord, I dont know why your nose so wide, none of my people got noses like that. And I cant even drag a comb through that nappy hair.

What I was was not enough. I was wrong, I needed correction. I was to become a scrubbed slate, detached from my own history. If I was to have any story at all, I had to grant anyone and everyone else permission to write itany beginning, any middle, any outcome.

I was Black and female. As such, I was taught that the world would tell me what and who I was. What we are.

We are the color pulsing beneath the closed eye, the tinge of a room at moonfall, we are steady suspect since we share our hue with the night. Because we are never seen clearlyconsistently spied-upon through a safely-distanced shroudwe are diminished, trivialized, spoken of as stain. We are the rollicking hips and the curious hair, the bristling oddity, the tangled waft of shea and spiced oil, the throats that refuse to constrict. Everyone has had a go at us, poking fervently at spaces in our spirit, plumping us for consumption, starving us for spectacle, killing us for sport. Were seen as the blaring gold tooth, the tangling weave, the ungrammatical phrase, the public exhibition, the occasional inconvenient corpse. We are objectified, analyzed, and rearranged to fit someone elses perception of what a voiceless woman should be.