POETRY OF THE FIRST WORLD WAR

POETRY OF THE FIRST WORLD WAR

AN ANTHOLOGY

Edited by

TIM KENDALL

Great Clarendon Street, Oxford OX 2 6 DP

United Kingdom

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the Universitys objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and in certain other countries

Selection and editorial material Tim Kendall 2013

For additional copyright information see Acknowledgements, pp. 3012

The moral rights of the author have been asserted

First published 2013

Impression: 1

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by licence or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organization. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above

You must not circulate this work in any other form

and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer

Published in the United States of America by Oxford University Press

198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016, United States of America

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

Data available

Library of Congress Control Number: 2013938931

ISBN 9780199581443

Printed by

Clays Ltd, St Ives plc

Links to third party websites are provided by Oxford in good faith and for information only. Oxford disclaims any responsibility for the materials contained in any third party website referenced in this work.

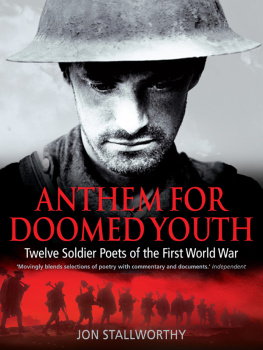

For Jon Stallworthy

D O you know what would hold me together on a battlefield?, Wilfred Owen wrote to his mother in December 1914, before providing an unlikely answer: The sense that I was perpetuating the language in which Keats and the rest of them wrote! Although few among Owens contemporaries would have expressed their resolve quite like that, pride in their nations literary achievements was

During the First World War, poetry became established as the barometer for the nations values: the greater the

The close identification well rewarded. Three establishment versifiersOwen Seaman, Henry Newbolt, and William Watsonreceived knighthoods (in 1914, 1915, and 1917 respectively), the last after publishing a poetic eulogy in honour of the prime minister, David Lloyd George.

The grey eminences may not have noticed, but the War arrived at a time when English poetry was already being refashioned. A new generation of poetsthe

Despite (or because of) its popular appeal, Georgianism has not been treated kindly by subsequent generations of literary historians, who dismiss its style as ill equipped to face the trauma of mass technological warfare. In such accounts, the soldierpoets were shell-shocked Georgians, their aesthetic assumptions having rendered them particularly vulnerable to the fronts unimagined brutalities; Modernists, meanwhile, were experimenters, responding with appropriate urgency to a broken world. This overlooks the Georgian origins of most surviving war poetry: the only Modernist soldierpoet of any note, David Jones, did not publish his masterpiece of the War, In Parenthesis, until nearly twenty years after the Armistice. It also overlooks the capacity for radicalism within Georgian poetry itself. Probably the first poet to describe trench life in its actualities was a civilian, Wilfrid Gibson, whose work would appear in all five of the Georgian anthologies. Breakfast, a short lyric written within two months of the Wars outbreak, exemplifies the Georgian emphasis on tonal restraint and a deliberately narrow formal and linguistic range:

We ate our breakfast lying on our backs,

Because the shells were screeching overhead.

I bet a rasher to a loaf of bread

That Hull United would beat Halifax

When Jimmy Stainthorp played full-back instead

Of Billy Bradford. Ginger raised his head

And cursed, and took the bet; and dropt back dead.

We ate our breakfast lying on our backs,

Because the shells were screeching overhead.

Breakfast could not be further from the loud rhetorical styles that dominated the early months of the War. The paucity of rhymes, the repetitions, the ordinariness of the dictionthe poem derives its power from its understating of high drama. A soldier dies, but Gibson ends where he began as though nothing has changed. At its best, the spare style of Georgianism was perfectly suited to its new us, deliberately jarred the reader), but they did so from within a context of Georgian beliefs and practices.

The Georgian poetry anthologies provided an influential model for satisfying the needs of a reading public which, with so much verse appearing at such speed, relied increasingly on editors to discern and discriminate. The war years established the anthology as the ages most representative literary medium. Dozens of anthologies appeared before the Armistice. Some focused on poetry by civilians, others on poetry by soldiers; some included foreign nationals from the Allied powers; some concentrated on England at the expense of the rest of Britain. Many continued to be filled with the kind of verse exemplified by the poet laureate, Robert Bridges:

Thou careless, awake!

Thou peacemaker, fight!

Stand, England, for honour,

And God guard the Right!

Older poems on military subjects surged in popularity: Rudyard Kiplings Barrack-Room Ballads, first published in the mid-1890s, sold 29,000 copies in 1915 alone. But longevity was rare. In 1917, E. B. Osborn boldly announced that wartime verse by civilians had nearly all been cast ere now into the waste-paper basket of oblivion. quality.

near Mametz Wood.

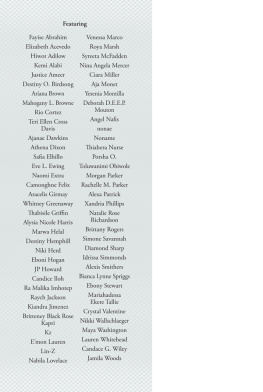

The soldierpoets came from all backgrounds: Sassoon, Shaw Stewart, and Grenfell were landed gentry, and therefore conformed to what has since become the widespread (and inaccurate) perception that the officer classes were all educated at public schools and Oxbridge. But officers such as Rickword and Owen were products of grammar schools, Private Gurney was the son of a tailor, and Private Rosenberg an East End Jew so desperately impoverished that his pacifist principles gave way to his need to earn money by enlisting. Their various circumstances point to one reason why the War produced so many fine writers: the conscripted army was far bigger, better educated, and more socially diverse than any that had preceded it. Unsurprisingly, attitudes to the War were just as various; Owens desire to plead the sufferings of his men could hardly be shared by Rosenberg, who was the victim of anti-Semitic bullying within his battalion.

The well-worn argument that poets underwent a journey from idealism to bitterness as the War progressed is supported by Jones, who remembered a change around the start of the Battle of the Somme (July 1916) as the War hardened into

The soldierpoets who were capable of seeing and writing are realities: dulce et decorum it is certainly not, to die in a gas attack with blood gargling from the froth-corrupted lungs. Most soldierpoetslike most soldiersbelieved the War to be necessary, but wanted the costs acknowledged and the truths told.

Next page