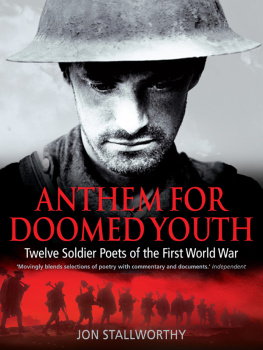

ANTHEM

FOR

DOOMED

YOUTH

Twelve Soldier Poets

of the First World War

JON STALLWORTHY

Published in association with the Imperial War Museum

CONSTABLE LONDON

Constable & Robinson Ltd

55-56 Russell Square

London

WC1B 4HP

www.constablerobinson.com

First published in the UK in 2002 by Constable,

an imprint of Constable & Robinson Ltd,

in association with the Imperial War Museum

This paperback edition published by Constable in 2013

Copyright 2002, 2005 in introductions and captions: Jon Stallworthy

Copyright 2002, 2005 in illustrations: Imperial War Museum, with the

exceptions listed on page 191

Copyright 2002, 2005 Constable & Robinson Ltd

All rights reserved. This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, re-sold, hired out or otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

A copy of the British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data is available from the British Library

ISBN 1-84529-221-9 (pbk)

eISBN: 978-1-4721-1005-3

Printed and Bound in the UK

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

Cover photographs: Imperial War Museum

Cover design: www.eamessurman.com

Contents

Introduction

M ore has been written about the First World War than about any other war in history but, inevitably, many of the questions it raises remain and will remain unanswered. It may be appropriate, therefore, to begin an introduction to some of the soldier poets of that war with a question: when and where were the following stanzas from Herbert Cadetts poem, The Song of Modern Mars, written?

Three miles of trench and a mile of men

In a rough-hewn, slop-shop grave;

Spades and a volley for one in ten

Heres a hip! hurrah! for the brave.

[...]

Crimson flecks on a sand-coloured mound,

Like rays of the rosy morn,

And splashes of red on a khaki ground,

Like poppies in fields of corn.

The answer is not London or Flanders, 1915, but London or South Africa, 1900. The war still known so many wars later by the epithet Great made such an impact on the consciousness of Western Europe that it erased from folk-memory the scars of former conflicts. War poetry began and ended with the First World War, wrote a reviewer in The Times Literary Supplement (September 1972). He went on: There were poems written about earlier wars but they were battle-pieces, not war poems in the 191418 sense. Paul Fussell, the American author of what is, in many ways, the most searching and satisfying study of writing about that war, The Great War and Modern Memory, supports this view. The war will not be understood in traditional terms, he says; the machine gun alone makes it so special and unexampled. Yet, over the mile of men in their South African mass-grave, sounds

[...] The rat-tat-tat of the Maxim gun

A machine-made funeral knell.

In his excellent study of the poetry of the AngloBoer War, Drummer Hodge, Malvern van Wyk Smith has shown how in Britain, at the start of that war in 1899, militarist and pacifist doctrines were clearly defined and opposed. Because of the Education Acts of 1870 and 1876, the army that had sailed for South Africa was the first literate army in history, and the British Tommy sent home letters and poems that poignantly anticipate those his sons and nephews were to send back from Gallipoli and the Western Front in the Great War.

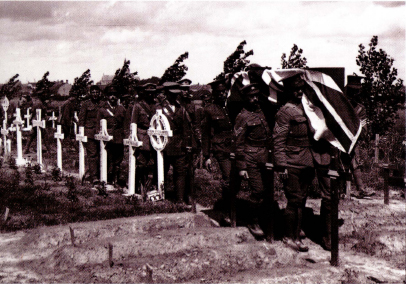

British soldiers killed in the battle at Spion Kop, January 1900

Those factual and often bitter accounts of combat had been forgotten by 1914, when the Great War was greeted, in many quarters, with the curious gaiety and exhilaration that Philip Larkin captured so vividly in his poem MCMXIV (Roman numerals, as seen on war-memorials, denoting 1914; letters that now seem almost as remote as the hieroglyphs in tombs of the pharaohs). Larkins camera focuses on the queues outside the recruiting offices:

Those long uneven lines

Standing as patiently

As if they were stretched outside

The Oval or Villa Park,

The crowns of hats, the sun

On moustached archaic faces

Grinning as if it were all

An August Bank Holiday lark;

Rupert Brooke caught the mood of that moment in a sonnet to which he gave the paradoxical title of Peace. It begins:

Now, God be thanked Who has matched us with His hour,

And caught our youth, and wakened us from sleeping,

With hand made sure, clear eye, and sharpened power,

To turn, as swimmers into cleanness leaping,

Glad from a world grown old and cold and weary,

Leave the sick hearts that honour could not move,

And half-men, and their dirty songs and dreary,

And all the little emptiness of love!

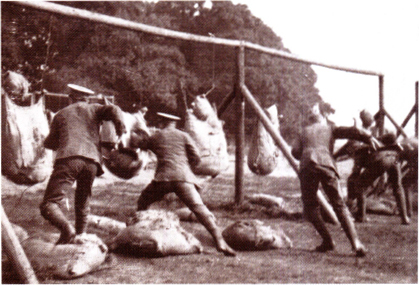

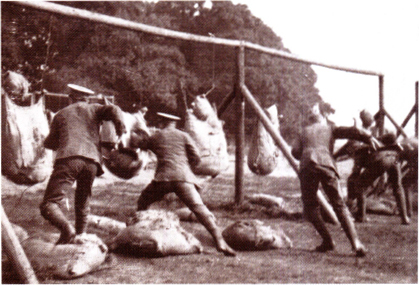

Recruits of the Lincolnshire Regiment in training, September 1914

Brookes first line Now, God be thanked Who has matched us with His hour and the hand and the hearts that follow reveal one of his sources to be the hymn, and ironically a hymn that has been translated from the German, beginning

Now thank we all our God

With heart, and hands and voices.

Men of the Honorable Artillery Company at bayonet practice, 1914

In times of war and national calamity, large numbers of people seldom seen in church or bookshop will turn for consolation and inspiration to religion and poetry. Never was the interaction of these two more clearly demonstrated than in the Great War.

On Easter Sunday 1915, the Dean of St Pauls preached in the Cathedral to a large congregation of widows, parents and orphans. Dean Inge gave as his text Isaiah 26: 19. The dead shall live, my body shall arise. Awake and sing, ye that dwell in the dust. He had just read a poem on this subject, he said, a sonnet by a young writer who would, he ventured to think, take rank with our great poets so potent was a time of trouble to evoke genius which must otherwise have slumbered. He then read aloud Rupert Brookes The Soldier (see pp. 2021), and remarked that the expression of a pure and elevated patriotism had never found a nobler expression. So Brooke the soldier-poet was canonized by the Church, and many other poets, soldiers and civilians alike found inspiration for their battle hymns, elegies, exhortations, in Hymns Ancient and Modern:

For a Europes flouted laws

We the sword reluctant drew,

Righteous in a righteous cause:

Britons, we WILL see it through!

R. M. Freeman, from The War Cry

Many of the first poets to respond in print to the events of 1914 and 1915 had left their public schools with a second, secular source of poetic inspiration. This was the public-school song, itself derived from the hymnal of the established Church. It can be heard behind R. E. Verndes poem The Call:

Recruits at Whitechapel Recruiting Office, 1914