CONTENTS

About the Book

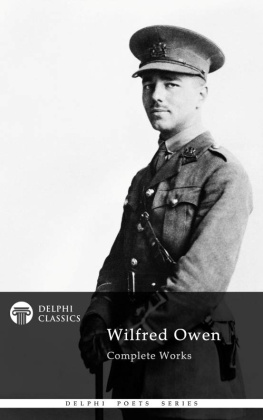

This selection of Wilfred Owens war poems is being published partly to provide an ideal edition of the poems for schools, who essentially read the war poems and need a short, thorough edition. It contains a new introduction by Jon Stallworthy, which is aimed at a general audience, but will be thorough and academic enough to work for schools as well. Constable have a similar edition planned, but Chattos will be out first, and contains copyright material unavailable to other editions.

INTRODUCTION

Orpheus, the pagan saint of poets, went through hell and came back singing. In twentieth-century mythology, the singer wears a steel helmet and makes his descent down some profound dull tunnel in the stinking mud of the Western Front. For most readers of English poetry, the face under the helmet is that of Wilfred Owen.

E ARLY Y EARS

Wilfred Edward Salter Owen was born in Oswestry on 18 March 1893. His parents were then living in a spacious and comfortable house owned by his grandfather, Edward Shaw. At his death two years later, this former mayor of the city was found to be almost bankrupt, and Tom Owen was obliged to move with his wife and son to lodgings in the back streets of Birkenhead. They carried with them vivid memories of their vanished prosperity, and Susan Owen resolved that her adored son should in time restore the family to its rightful gentility. She was a devout Evangelical Christian and, under her strong influence, Wilfred grew into a serious and slightly priggish boy. He started school at seven, and two or three years later discovered his vocation during an idyllic Cheshire holiday with his mother (who had left her other children, Mary, Harold and Colin, with their father): At Broxton, by the Hill, he wrote, was born my poethood.

Early in 1907, the family moved to Shrewsbury where Tom Owen had been appointed Assistant Superintendent of the Joint Railways. Wilfred went to the Shrewsbury Technical School and worked hard and successfully, especially at botany and English literature. His interest in poetry (particularly that of Keats) was growing, but still exceeded by his preoccupation with religion. Every day he read a passage from the Bible appointed by the Scripture Union, with the aid of its notes, and sometimes on Sundays would rearrange his parents sitting-room to represent a church. Then, wearing a linen surplice and cardboard mitre made by his mother, he would summon the family to an evening service complete with sermon.

He was also developing outdoor interests. With his cousins Vera and Leslie Gunston, he formed an Astronomical, Geological and Botanical Society (of three members). As his enthusiasm for botany had led him to the study of geology, so this in turn led him to archaeology and, in 1909, he made the first of many expeditions to the site of the Roman city of Uriconium at Wroxeter, east of Shrewsbury. He left school in 1911 , eager to go to university, and passed the University of London matriculation exam, though not with the first-class honours necessary to win him the scholarship he needed. Disappointed, he accepted the offer of an unpaid position as lay assistant to the Rev. Herbert Wigan, Vicar of Dunsden, a village outside Reading. In return for help with his parish duties, Wigan was to give him free board and lodging and some tuition to prepare him for the university entrance exam. The arrangement was not a success. Wigan had no interest in literature, and Owen soon lost interest in theology, the only topic offered for tuition. Over the coming months, however, he attended botany classes at University College, Reading, and was encouraged both in his writing and in his literary studies by the Head of the English department. Meanwhile, influenced by his reading of Shelley, atheist and revolutionary (whom he was happy to learn had lived nearby), as well as the Gospels, he gave practical help to the poor of the parish. His letters home show the first signs of the compassion that would characterize his poems from the Western Front:

I am increasingly liberalizing my thought, spite of the Vicars strong Conservatism. And when he paws his beard, and wonders whether 10. is too high a price for new curtains for the dining room, (in place of the faded ones you saw); then the fires smoulder From what I hear straight from the tight-pursed lips of wolfish ploughmen in their cottages, I might say there is material for another revolution. Perhaps men will strike , not with absence from work; but with arms at work. Am I for or against upheaval? I know not; I am not happy in these thoughts; yet they press heavy upon me. I am happier when I go to distribute dole

To poor sick people, richer in His eyes ,

Who ransomed us, and haler too than I .

The Vicar had been praying for a religious revival in the parish and, early in 1913, it arrived like a spring tide, sweeping converts into church but leaving Owen stranded on the recognition that literature meant more to him than evangelical religion. He had to explain this to the Vicar, who was strongly disapproving both of his assistants altered priorities and of his warm (but probably innocuous) friendship with one of the village boys. Owens letters to his mother record a developing crisis:

Escape from this hotbed of religion I now long for more than I could ever have conceived a year and three months ago

To leave Dunsden will mean a terrible bust-up; but I have no intention of sneaking away by smuggling my reasons down the back-stairs. I will vanish in thunder and lightening, if I go at all.

Go he did, in February 1913, on the verge of a nervous breakdown and with congestion of the lungs that kept him in bed for more than a month. In July he sat a scholarship exam for University College, Reading, but failed, and in mid-September crossed the Channel to take up a part-time post teaching English at the Berlitz School in Bordeaux. Over the next two years, he grew to love France, its language and its literature, and had reached perhaps the highest point of happiness that life would offer him, tutoring an eleven-year-old French girl in her parents Pyrenean villa, when, on 4 August 1914, Germany invaded Belgium and war was declared.

E ARLY I NFLUENCES AND P OEMS

The earliest and probably the most important literary influence on Wilfred Owen (as on so many other writers in English) was the Bible. This he would have heard read aloud before he could read it for himself: reading it then under his mothers direction, and that of the Scripture Union notes, he acquired the habit of close reading that would stand him in good stead when he came to literary texts. The fact that he ascribed the birth of his poethood to his Broxton holiday of 1903 or 1904 suggests that he was there introduced to poetry. If so, it was almost certainly Keatss poetry, clearly audible behind his own first attempts at writing verse. The earliest of these to survive was probably To Poesy (an ironical beginning for a poet whose most famous manifesto would declare: Above all I am not concerned with Poetry). This bears a marked resemblance to Keatss The Fall of Hyperion, as other of Owens adolescent poems would acknowledge in their titles and confirm in their texts a debt to the older poet: Before reading a Biography of Keats for the first time (On First Looking into Chapmans Homer), Sonnet Written at Teignmouth, on a pilgrimage to Keatss house (Sonnet Written in the Cottage where Burns was Born), and On seeing a Lock of Keats Hair (On Seeing a Lock of Miltons Hair).

Influenced perhaps by Keatss dictum that A long poem is a test of Invention, which I take to be the polar star of poetry, as Fancy is the sails, and Imagination the rudder, Owen at Dunsden produced a verse rendering of Hans Andersens fairy tale The Little Mermaid. His mother would have approved of this particular tale: a romantic story of sacrificial love and acute bodily suffering nobly borne, it offered scope for those painterly descriptions of physical beauty that he so enjoyed. A mermaid heroine would have appealed to an admirer of Keatss Lamia, and he chose the eight-line stanza of Isabella. The texture of the verse is markedly Keatsian and moves with ease and assurance through its seventy-seven stanzas. One, describing the approach of a storm, contains an image and an onomatopoeic use of language that anticipates the later poems from the Western Front:

Next page