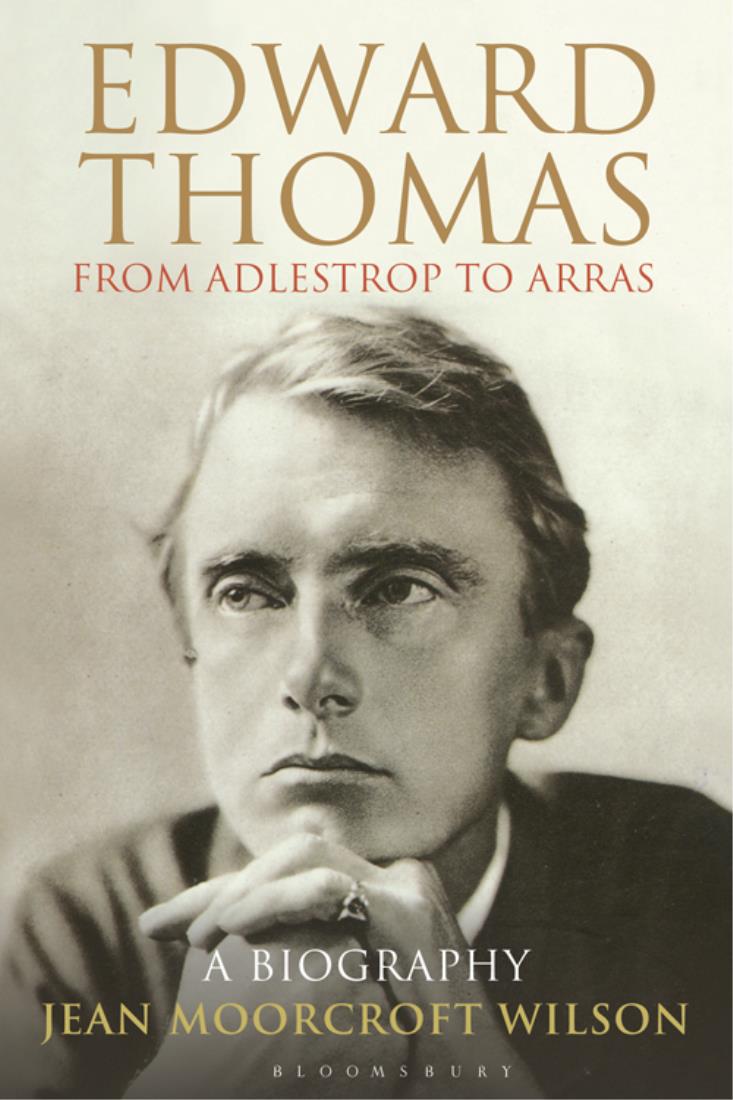

EDWARD THOMAS

From Adlestrop to Arras:

A Biography

Jean Moorcroft Wilson

For Cecil Woolf

&

in memory of

Sir Martin Gilbert (19362015)

First Plate Section

Second plate section

Sir, the biographical part of literature is what I love most. Give us as many anecdotes as you can.

Dr Johnson

Line Drawing of Edward Thomas by his brother Ernest Henry Thomas, 1905, National Portrait Gallery, London.

A stopped watch, a half-filled clay pipe and a pocket-diary with curiously creased pages were among the personal effects of Edward Thomas sent home to his distraught wife after his death at the Battle of Arras on 9 April 1917. From such sad memorials she drew what comfort she could, coming to believe that her husbands body had remained unblemished and that the shell which killed him had done so simply by drawing the breath from his body. The true details of Thomas's death have remained obscured, generations of biographers repeating Helen Thomas's highly subjective version. I am now able to give the actual, very different facts here for the first time.

Thomas did not live to see the first edition of his poems, which were not published as a collection until after his death, but they have never since been out of print. For almost a century his work has attracted strong advocates and disciples, including some of the best-known names in modern poetry Thomas Hardy, W. H. Auden, Dylan Thomas, Philip Larkin, Ted Hughes and Seamus Heaney among them. (Hughes famously called him the father of us all.) He features on the First World War memorial plaque in Westminster Abbey, yet his status among the privileged few to appear there is still uncertain. His name is perhaps not currently as widely known as that of Rupert Brooke, Wilfred Owen, Siegfried Sassoon or even Isaac Rosenberg.

Yet with the exception of Rosenberg and his fellow-Modernist David Jones, Thomass distinctively modern sensibility (to use F. R. Leaviss phrase),

A characteristic poem by Thomas, in contrast to the apparently more composed work of the Georgians, gives the sense of a jotting down of random impressions and feelings, expressed in quiet, reflective speech. His exploration of such topics as memory, identity, disintegration, directionlessness and loss anticipate many of the themes of modern poetry. In addition, his verse is, as Longley also argues, psychoanalytical before psychoanalytical criticism, his ecological vision a pioneer of ecocriticism and his environmentalism prophetic of our own concerns. A poem like Old Man, for instance, which opens with a meditation on the herb of that name otherwise known as lads love, unfolds through the simple action of a child pluck[ing] a feather from the door-side bush / Whenever she goes in or out of the house and the narrator wondering how much she will recall of the scene in later life. It is a deceptively artless start which enables the poet to arrive without apparent contrivance, yet with a sense of inevitability, at his regretful conclusion:

As for myself,

Where first I met the bitter scent is lost.

I, too, often shrivel the grey shreds,

Sniff them and think and sniff again and try

Once more to think what it is I am remembering,

Always in vain. I cannot like the scent,

Yet I would rather give up others more sweet,

With no meaning, than this bitter one.

I have mislaid the key. I sniff the spray

And think of nothing; I see and I hear nothing;

Yet seem, too, to be listening, lying in wait

For what I should, yet never can, remember:

No garden appears, no path, no hoar-green bush

Of Lads-love, or Old Man, no child beside,

Neither father nor mother, nor any playmate;

Only an avenue, dark, nameless, without end.

The elusiveness here, as Motion suggests, is so scrupulously reflected in the disarmingly low-keyed tone of voice

Thomass verse was, in fact, written between 1914 and 1917 and his most famous English contemporaries were all war poets. Here, too, he occupies a significant central position. Neither as jingoistic as Brooke, Julian Grenfell, or Sassoon before he experienced front-line conditions, nor as critical of the conflict as the later Sassoon or Owen, Thomass more measured approach most nearly resembles another relatively neglected war poet, Charles Hamilton Sorley. In both cases, and despite a considerable age difference, their attitude towards the war is remarkably mature and perceptive from the start. They also share a strong sense of the past and profound love of the countryside. In Thomass case this eco-historical sense leads him, in poems like The Gallows and The Combe, for instance, to correlate the war with human violence to other species, a concept which again resonates with modern readers:

The Combe was ever dark, ancient and dark.

... But far more ancient and dark

The Combe looks since they killed the badger there,

Dug him out and gave him to the hounds,

That most ancient Briton of English beasts.

There are those who would deny that Thomas is a war poet at all, including such respected critics of the genre as Bernard Bergonzi and John H. Johnston. Some prefer to include him in the Georgian camp, or to label him a Pastoral, Nature or a Mystic poet. of war than This is no petty case of right or wrong or In Memoriam (Easter 1915) which refers more openly to the war:

The flowers left thick at nightfall in the wood

This Eastertide call into mind the men,

Now far from home, who, with their sweethearts, should

Have gathered them and will do never again.

For as Larkin wrote in a review of Wilfred Owens Collected Poems: A war poet is not one who chooses to commemorate or celebrate a war, but one who reacts against having a war thrust upon him.) It may be that this problem in placing Thomas is another factor which has militated against his wider acceptance. An age of ever-growing interdisciplinary studies may now be more receptive to his versatility and wide range.

His life alone makes for absorbing reading: his marriage to Helen, the daughter of his first literary mentor, James Ashcroft Noble, while still at Oxford; his dependence on laudanum; his rejection of a safe Civil Service career and determination to make a living by writing; his friendships with many of the well-known magazine editors and writers of the Edwardian and early Georgian period Edward Garnett, Rupert Brooke, Gordon Bottomley, Joseph Conrad, Lascelles Abercrombie, Hilaire Belloc, Wilfrid Gibson, Walter de la Mare and many others; his thoughts of suicide; his infatuation with a schoolgirl over a decade younger than himself and later a beautiful, but married woman; his meeting with Robert Frost in 1913 and subsequent shift from prose to poetry, even more unusual than Sassoons move in the other direction; his relationship with Eleanor Farjeon, who entered into a curious three-sided relationship with him and his wife; his decision to enlist in the army at the age of 37; and his death in France on 9 April 1917, the first day of the Battle of Arras. It is the stuff myths are made of and posterity has been quick to oblige. While making his name better known, however, this has threatened to obscure his worth as a writer.

The first and most enduring of these myths is that when Helen Nobles pregnancy obliged Thomas to marry before even finishing his degree, he was then forced to support his wife and family by accepting any work available and that all his subsequent prose is hackwork. One admirer of his poetry, for instance, referred as recently as 2008 to Thomas churning out prose. Yet Thomass critical biography of Richard Jefferies is a classic of the genre and still a standard work on the subject, his topographical and travel books, like

Next page