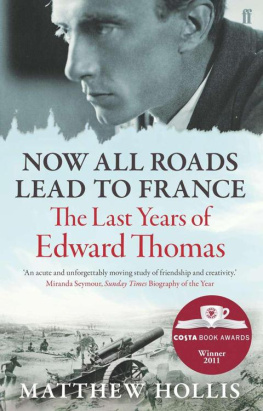

Praise for Now All Roads Lead to France:

Finally gives the poets poet among the dead of the Great War the measured and moving biographical treatment he deserves. Jonathan Bate, Sunday Telegraph Books of the Year

With calm grace and candid respect, Hollis gives contemporary relevance to the last powerful works of [Edward Thomas]. Iain Finlayson, The Times Books of the Year

Holliss great achievement is to use the odd shape of Thomass verse life as a way to explore the state of British poetry on the eve of the Great War, poised between Georgian lyricism and stark modernism. He triumphantly demonstrates how, far from being a baggy or moribund genre, biography can be a sharp tool of literary criticism. Kathryn Hughes, Guardian Books of the Year

One of the years most engrossing biographies sensitively recounted the growth-spurt in Thomass art. Boyd Tonkin, Independent Books of the Year

The best book about poetry moving and insightful nothing I have come across before has got so well the feeling of how that complex symbiosis worked and how the parting of Thomas and Frost was as significant in its way as their first encounter. By its end the book is the perfect setting for Thomass perfect poems. Bernard ODonoghue, TLS Books of the Year

Brilliant and superbly written. Nigel Jones, Sunday Telegraph Book of the Week

Extremely readable Thomas is well served by Holliss clear-eyed sympathy. Sean OBrien, Independent Book of the Week

Exceptionally fine perhaps, above all, a gentle reminder that poetry can be almost as essential to the human spirit as breathing. Craig Brown, Mail on Sunday Book of the Week

Like Edward Thomass poetry, Now All Roads Lead to France is a work of careful, unobtrusive excellence, subtle insight and great emotional power. It tells the story of a compelling figure from a half-forgotten England whose influence on contemporary writing seems to grow and grow. Adam Foulds

Matthew Holliss superb biography focuses on what transformed a talented journalist into one of the most highly regarded nature poets of the twentieth century. Sameer Rahim, Daily Telegraph

My favourite biography of 2011 is Matthew Holliss eloquently perceptive Now All Roads Lead to France, an atmospheric study of poet Edward Thomas, his life and times, and particularly his friendship with Robert Frost which led him to nature poetry and ultimately to powerful lyrics shaped by war. Eileen Battersby

Thoughtful and scrupulous A bravura critical performance. John Carey, Sunday Times

Elegant and insightful A brilliant, even inspiring biography. Hugh MacDonald, Herald

Excellent and highly readable Hollis writes a fascinating and knowledgeable study of England and Englishness of the era. Gerald Dawe, Irish Times

Wonderful Hollis tells this tale with a sigh but also with dry wit, deep compassion and a poets eye for evocative detail. Paul Carter, Daily Mail

Hollis writes with great sensitivity and understanding The enormous strength of Holliss study is the way in which it portrays the different influences that suddenly converged to produce a great poet. Mark Bostridge, Literary Review

This biography is a marvel. Thomas McCarthy, Irish Examiner

An evocation of a lost England that Thomas himself elegised so movingly in the nature poems that have found an enduring place in the canon of British literature. Jason Cowley, Financial Times

Compelling. Paul Dunn, The Times

[Thomass] discovery of his own considerable talent and place in the world as that world was in the process of falling apart is almost unbearably poignant Wonderful. Wayne Gooderham, Time Out

Now All Roads Lead to France tells a story so delicate, tragic and inevitable , and which contains examples of such searingly perfect poetry, that all I can say is that this is a beautiful book. Read it. Robert Giddings, Tribune

Compelling Among the most fascinating aspects of Holliss book is showing how Thomas transformed the contents of his past notebooks into powerful and haunting verse. Hugh Cecil, Spectator

Hollis, a poet himself, is at his best in examining this extraordinary creative friendship with Frost Riveting. James Fergusson, Country Life

for Mum

and I rose up, and knew that I was tired, and continued my journey

EDWARD THOMAS , Light and Twilight

Contents

Edward Thomas spent the day before he died under particularly heavy bombardment. The shell that fell two yards from where he stood should have killed him, but instead it was a rare dud. Back at billet, the men teased him on his lucky escape; someone remarked that a fellow with Thomass luck should be safe wherever he went. The next morning was the first of the Arras offensive. Easter Monday dawned cold and wintry. The infantry in the trenches fixed their bayonets and tightened their grip around their rifles; behind them, the artillery made their final preparations to the loading and the fusing of the shells. Thomas had started late to the Observation Post; he had not rung through his arrival when the bombardment began. The Allied assault was so immense that some Germans were captured half-dressed; others did not have time to put on their boots and fled barefoot through the mud and snow. British troops sang and danced in what only a few hours before had been no- mans-land . Edward Thomas left the dugout behind his post and leaned into the opening to take a moment to fill his pipe. A shell passed so close to him that the blast of air stopped his heart. He fell without a mark on his body.

There has been opened at 35, Devonshire-street, Theobalds-road , a Poetry Bookshop, where you can see any and every volume of modern poetry. It will be an impressive and, perhaps, an instructive sight.

EDWARD THOMAS , Daily Chronicle, 14 January 1913

At the cramped premises off Theobalds Road in Bloomsbury, Harold Monro was preparing for the opening of his new bookshop . Before the turn of the year, Monro had announced that on 1 January 1913 he would open a poetry bookshop in the heart of London, five minutes walk from the British Museum. It would be devoted to the sale of verse in all its forms books, pamphlets, rhyme sheets and magazines and would be both a venue for poetry readings and the base for an intrepid publishing programme. Let us hope that we shall succeed in reviving, at least, the best traits and qualities of so estimable an institution as the pleasant and intimate bookshop of the past. To Monro that revival meant something particular: wooden settles, a coal fire, unvarnished oak bookcases, a selection of literary reviews lain out on the shop table and, completing the scene, Monros cat Pinknose curled up beside the hearth.

The premises stood on a poorly lit, narrow street between the faded charm of the eighteenth-century Queen Square and the din of the tramways thundering up Theobalds Road. The shop occupied a small ground-floor room, twelve feet across and lit from the street by a fine five-panelled window; in the back was an office from where Monro ran his publishing empire. Upstairs was a dignified drawing room where the twice-weekly poetry

On 8 January 1913, a week later than planned, the Bookshop officially opened its doors. Poets, journalists, critics, readers, patrons: they came in their dozens, until barely a foot of standing room was left unclaimed. That afternoon and the one that followed, three hundred people crammed into the little shop, filling the staircase and the first-floor drawing room; for the capitals poets it was an occasion not to be missed. Wilfrid Gibson, the most popular young poet of the decade, was already resident in the attic rooms and had only to walk downstairs, while the wooden-legged, self-declared super-tramp, W. H. Davies, had hobbled in all the way from Kent. Lascelles (he said it like tassels) Abercrombie had been invited to open the proceedings, but speculated that to ask a man of his years might seem tactless to the elders (he was about to turn thirty-two); W. B. Yeats diplomatically suggested that perhaps the honour should not befall a poet of any description . But Monro was adamant, and turned to the fifty-year-old Henry Newbolt, then Chair of Poetry at the Royal Society of Literature, to perform the ceremony. At Newbolts side was Edward Marsh, Secretary to the First Lord of the Admiralty Winston Churchill and editor of an anthology launched that day that would become one of the best-selling poetry series of the century. Among its contributors was the twenty-five-year-old Rupert Brooke, who was in Cornwall that afternoon recovering from the strain of his fraught personal life but who would give a reading at the Bookshop before the month was out. F. S. Flint, a dynamic young civil servant and poet who spoke nine languages, took a place on the busy staircase and told the stranger beside him that he could tell by his shoes that he was an American. The shoes belonged to Robert Frost, newly arrived in London, who confessed that he should not have been there at all: