W. W. NORTON & COMPANY

New York London

For information about permission to reproduce selections from this book, write to Permissions, W.W. Norton & Company, Inc., 500 Fifth Avenue,

New York, NY 10110.

W. W. Norton & Company, Inc.

500 Fifth Avenue, New York, N.Y. 10110

www.wwnorton.com

W.W. Norton & Company Ltd.

Castle House, 75/76 Wells Street, London WIT 3 QT

Introduction by David M. Shribman

R OBERT F ROST was Americas preeminent poet, the winner of four Pulitzer Prizes, the most of any poet. He was called by The Times of London, in its obituary announcing his death in 1963, undoubtedly the most widely known and loved literary figure in America to which the paper added, in a separate editorial tribute, that his fame in England was such that, in mourning, we are also regretting a loss that feels to have happened at home. The President of the United States said of him that he had left a vacancy in the American spirit: His death impoverishes us all; but he has bequeathed his nation a body of imperishable verse from which Americans will forever gain joy and understanding. A year earlier, within an introduction for the British edition of Frosts final book of new poems, Englands Robert Graves had declared, The truth is that Frost was the first American who could be honestly reckoned a master-poet by world standards.

During the course of a career that spanned nearly a full half-centuryfrom his first published book, in 1914, until his deathRobert Frost attained immense prominence and popularity as a poet and man of letters. He was that rarity in literary life, celebrated by the general public and scholars alike. He was another rarity, too, an achievement matched in his century perhaps only by William Faulkner: a writer of high art inextricably bound to one region, but nonetheless inarguably regarded as nationaleven universal.

He was a poet of rural byways, at a time when the nation was building urban and interstate highways. He was a high priest of the leisure thought, at a time when the country worshipped the hurry of commerce. His focus often was on agriculture and the pastoral, at the high tide of industry. He seemed sturdily to be a remnant of the past, in a world that prayed at the altar of the future. He articulated big truths, in a century that perfected the big lie.

Yet Frost, the countryman in a country of cities and an apparent antique in the culture of the new, was as current as the morning newspaper, with mass appeal in the first mass-market, mass-culture nation. He appeared on the covers of literary magazines, such as The Atlantic Monthly and Saturday Review, but also on the covers of popular mega-circulation magazines, such as Time and Life. He was both well-regarded and well-loved.

As the years passed, awards flowed to him, cascaded in upon him. He was given more than forty honorary degrees, including ones from both Oxford and Cambridge, a dual tribute that had been accorded but two American writers before him, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow and James Russell Lowell, back in the nineteenth century. A mountain was named for him in his home state of Vermont. A unanimous vote of Congress, which had previously saluted him with formal resolutions on his seventy-fifth and eighty-fifth birthdays, led to the striking in his honor of a special gold medal, presented to him in 1962 on his eighty-eighth birthday. All this for a man who, as expressed in his poem A Considerable Speck, had none of the tenderer-than-thou / Collectivistic regimenting love / With which the modern world is being swept.

Frost from time to time retreated to the farm, but never was a hermit. Increasingly over the years, he became a public mana personage. And it was not too much to say that, as such, he embraced the public and it embraced him. During the closing period of his life, he referred to the publicality of his existencethe word is his, as was the profile. But this publicality wasnt something he took on only in grandfatherly old age (and indeed there was much to Frost, early and late, that was not grandfatherly, for his was a world of conflict, not confection). However, his role as a public figure was perhaps underlined by his appointment in 1958 as Consultant in Poetry at the Library of Congressequivalent to designation as Poet Laureate of the United Statesand being thereafter the Lbrarys Honorary Consultant in the Humanities.

During March of 1962, slightly more than a year after his having dramatically played a cameo role in John F. Kennedys presidential inauguration, he told a Florida interviewer: Ive been publicized more this year than ever in my life. It turns me outside in, or inside out. So much pleasant attention. But on the outside, that isnt where you write poetry.

For a man who was a student of the inner life, and who stirred the inner life of the public, being out in public was ironic, and he himself was struck by the many ironies it prompted. He went to the Soviet Union that year of 1962, engaging while there in an historic, much-publicized one-on-one meeting with Premier Nikita Khrushchev. (He had earlier been on cultural goodwill missions, also arranged by the State Department, to several countries: Brazil, Great Britain, Ireland, Israel, and Greece.) Later, to an Amherst College audience he said of his Soviet trip: My career as a teacher and as a writer has almost been wiped out by my going to Russia. I havent met anybody lately that doesnt know Ive been to Russia, though theyve never read one of my books.

Robert Frosts poetry has survived him, and in truth appears to have grown in renown. The utmost of ambition is, he wrote in a tribute to his fellow poet Edwin Arlington Robinson, to lodge a few poems where they will be hard to get rid of. Clearly, by that gauge, Frosts own poetic ambition has been monumentally realized and his reputation as a poet rendered amply secure.

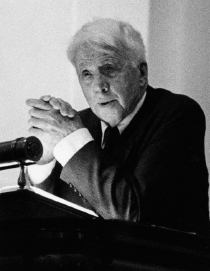

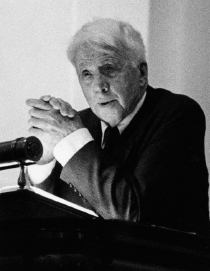

But most readers today do not know Frosthave had no way of knowing himin one of his most important roles, as teacher and lecturer. He was in fact one of Americas great teachers, one of its great presences as such, in a classroom or on a platform or stage. Although many years, many decades, have passed, there do remain today some for whom the memory of Robert Frost on an academic campuscollege or university or preparatory schoolendures with a special power and vividness, both intellectual and visual. He did with frequency speak elsewhere, before groups of various sorts and to general audiences, in cities and towns all across the land. But his academic audiences were those he liked best.

He himself had run away from collegesmost notably, as an undergraduate, from both Dartmouth and Harvard. (Dartmouth is my chief college, he told an interviewer in 1960, the first one I ran away from. I ran from Harvard later, but Dartmouth first. And sometimes he would add, as he did at Connecticut College in 1961, Dartmouths where I began my career, by running away.) However, he ran to colleges as well, acknowledging that they were the oxygen of poetry in America. I wouldnt be here, I wouldnt be in existence if it hadnt been for patronage of colleges, he said while speaking to a college audience in May of 1954, and exaggerating only slightly. In America we dont have any lords and ladies to patronize poets. And so we have to depend on colleges and the audiences that they give us. One of the best audiences the world ever had is what I call a mixed town-and-gown audience in a college town. And thats whats given me my life, my living.