Contents

Guide

The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

Contents

For Devon, now and always

PREFACE

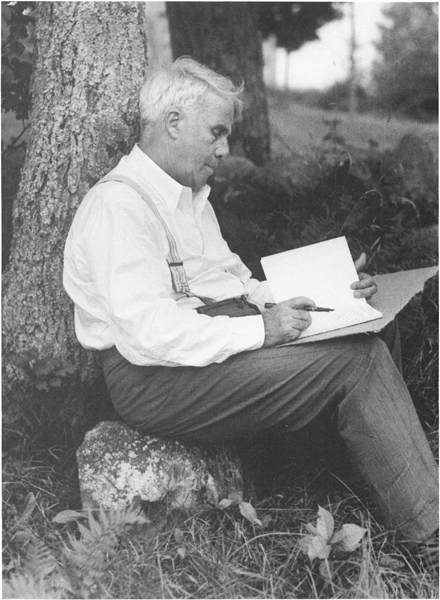

Robert Frost has been my favorite poet ever since the ninth grade, when I was handed a copy of his Selected Poems. Reading Dust of Snow and Stopping by Woods on a Snowy Evening, I experienced the physical and intellectual thrill of poetry for the first time. When I went to teach at Dartmouth College in 1975, the idea of writing a life of Frost first struck me. The opportunities at hand were certainly enticing. The archives at Dartmouth (where Frost had been a student in 1892) were full of tempting documents: manuscripts and drafts of poems, journals kept throughout Frosts career, hundreds of letters written or received by the poeta considerable portion of them never published. There were also countless tapes of readings and lectures, transcripts of public addresses, and miscellaneous accounts of Frost by others. I plunged immediately into this material.

There were many people who had known Frost in the immediate vicinity, such as Edward Connery Lathem, Richard Eberhart, Thomas Vance, Alexander Laing, Harold Bond, and John Sloan Dickey. I made a point of talking to as many of them about Frost as I could, and took notes for what I first planned as an article about Frost at Dartmouth. In fact, the chapters on Frosts tenure at Dartmouth as Ticknor fellow, in the forties, were largely written at this time, as was the part about his undergraduate days in Hanover. During this period I also met Robert Francis, a poet who had known Frost in Amherst for many years, and interviewed him on the subject of Frost. It was Francis who suggested to me that a full-scale life of Frost would be a good project, although I put this idea on a back burner.

In 1982 I joined the faculty at Middlebury Collegeyet another of Frosts haunts. He lived for a part of each year on a farm in Ripton (near Middlebury) from 1939 until his death in 1963, and was closely associated with the Bread Loaf Writers Conference, a summer program at Middlebury College. Not surprisingly, the Middlebury College Library was also rich in Frost documents. I resumed work on Frost at this time, and among those I interviewed were Reginald L. Cook, a longtime professor at Middlebury who had known Frost well; Victor Reichert, a rabbi and close friend of the poets; and Robert Penn Warren, who summered in Vermont and had known Frost for many years. These three redirected my thinking in important ways, and they are quoted throughout this volume.

Although I published several pieces about Frost in the eighties, this book lay in scattered chapters until the mid-nineties, when I resumed work on it full-time. I revisited the Dartmouth archives, reading through the two thousand pages of biographical notes left by Lawrance Thompson after his death, and made a careful study of his notebooks, which proved an invaluable resource. (The original set of Lawrance Thompsons notes are in the University of Virginia Library.) I also revisited Frost collections elsewhere, at Amherst College, the University of Virginia, and Plymouth State College. In particular, I want to thank Philip Cronenwett of the Dartmouth College Library and John Lancaster of the Amherst College Library for their help and support in the making of this book.

I was given extraordinary guidance in my research by Lesley Lee Francis, the poets granddaughter, and by Peter Gilbert, his executor. Edward Connery Lathem, Hyde Cox, Philip Booth, Peter J. Stanlis, Jack W. C. Hagstrom, William H. Pritchard, James M. Cox, William Cook, Donald E. Pease, F. D. Reeve, Alastair Reid, Peter Davison, Richard Wilbur, Robert Pack, Ed Ingebretsen, William Meredith, John Elder, Robert Hill, Donald G. Sheehy, Gore Vidal, and many others (who are acknowledged in the Notes and Sources) aided and abetted my work. I am deeply grateful to them all. In particular, Lathem, Stanlis, and Sheehy were kind enough to read a manuscript version of this book; they offered countless suggestions for revision, and I remain deeply grateful to them for their generosity and direction. I must also thank my editors, Allen Peacock and Victoria Hipps, for their assistance and advice.

With a few notable exceptions, the facts of Robert Frosts life were not in question. A procession of biographers, especially Lawrance Thompson and R. H. Winnick, have gone before me, and I remain in their debt. (In Frost and His Biographers, an afterword to this study, I examine in detail the line of previous biographical writing on Frost.) What was left for me was assimilation, arrangement, and emphasis: the work of constructing from the myriad details of Frosts life a coherent story. My narrative presents Frost as a major poet who struggled throughout his long life with depression, anxiety, self-doubt, and confusion. His family life was not often happy, and he experienced some extremely bad luck with his children. On the other hand, he was a man of immense fortitude, an attentive father, and an artist of the first order who understood what he must do to create a body of work of lasting significance, to lodge a few poems where they cant be gotten rid of easily, as he often said.

Robert Frost did what was necessary, for him, to achieve what he did, at times risking the welfare of others, even his own. Each major poem was, in the complex circumstances of his life, a feat of rescued sanity as well as a momentary stay against confusion, as he memorably put it. Each class brilliantly taught, each vivid public reading, each child comforted or cared for, each tender moment with his wife was accomplished by steadiness of vision and hard spiritual work. I hope that much becomes clear in the following pages.

This biographical study offers a comprehensive reading of the poets life and work. I have tried to understand how Frost got from day to day and from poem to poem, tracing his rich, always developing, intellectual and artistic life over many decades. My intention was not to supplant or overtake previous biographers and critics but merely to add a significant layer. I can say without fear of exaggeration that this life of Frost was a labor of love. It is one of the few books I have ever finished with deep reluctance.

ONCE BY THE PACIFIC

18741885

Europe might sink and the wave of her sinking sweep

And spend itself on our shore and we would not weep

Our cities would not even turn in their sleep.

Our faces are not that way or should not be

Our future is in the West on the other Sea.

F ROST, UNPUBLISHED FRAGMENT , 1892

I know San Francisco like my own face, Robert Frost once told an audience in that city, late in his life. Its where I came from, the first place I really knew. You always know where you come from, dont you?

Because Frost is so intimately associated with rural New England, one tends to forget that the first landscape printed on his imagination was both urban and Californian. That he came to appreciate, and to see in the imaginative way a poet must see, the imagery of Vermont and New Hampshire has something to do with the anomaly of coming late to it. Its as though he were dropped into the countryside north of Boston from outer space, and remained perpetually stunned by what he saw, Robert Penn Warren observed. I dont think you can overemphasize that aspect of Frost. A native takes, or may take, a place for granted; if you have to earn your citizenship, your locality, it requires a special focus.