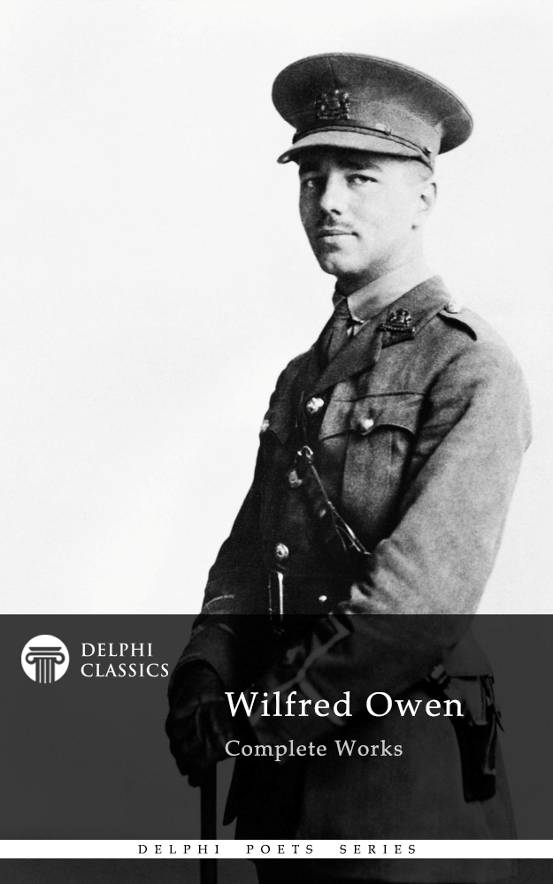

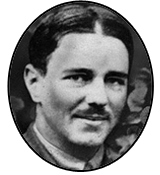

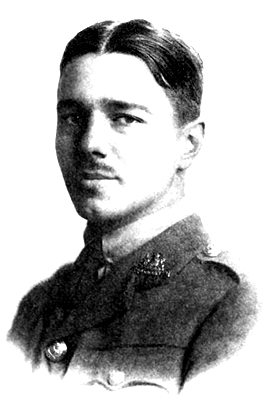

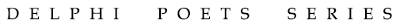

WILFRED OWEN

(1893-1918)

Contents

Delphi Classics 2012

Version 1

WILFRED OWEN

By Delphi Classics, 2012

COPYRIGHT

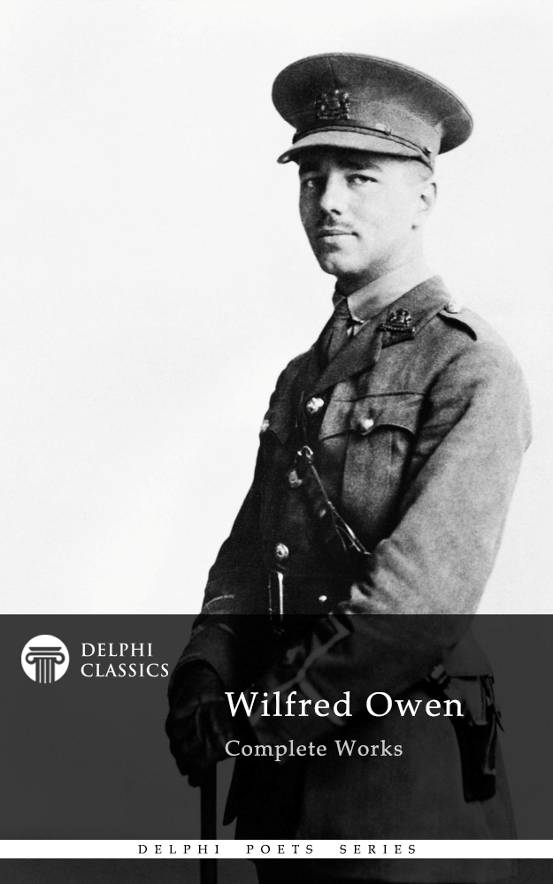

Wilfred Owen - Delphi Poets Series

First published in the United Kingdom in 2015 by Delphi Classics.

Delphi Classics, 2015.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form other than that in which it is published.

Delphi Classics

is an imprint of

Delphi Publishing Ltd

Hastings, East Sussex

United Kingdom

Contact: sales@delphiclassics.com

www.delphiclassics.com

NOTE

When reading poetry on an eReader, it is advisable to use a small font size, which will allow the lines of poetry to display correctly.

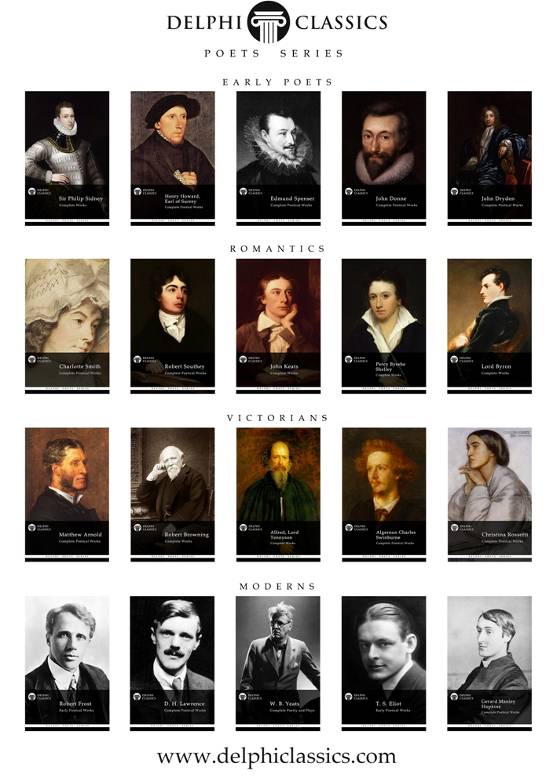

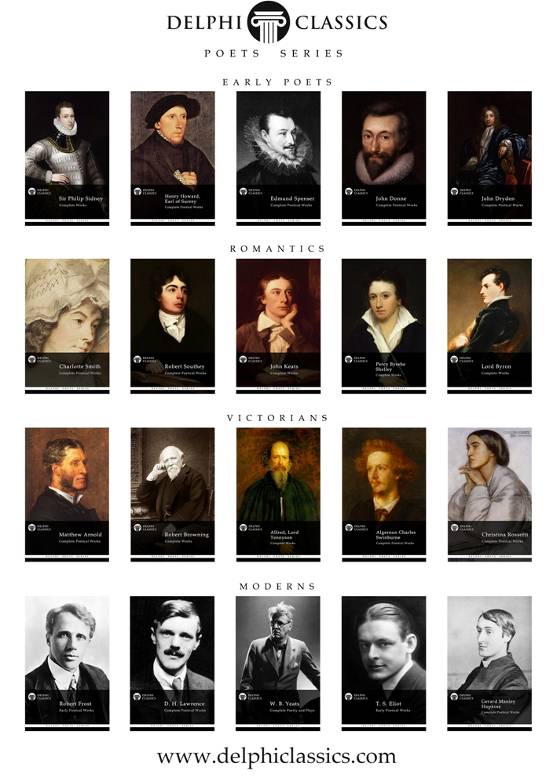

Also available:

Explore War Poets with Delphi Classics

For the first time in publishing history, readers can explore all the poems, rare fragments and the poets letters.

www.delphiclassics.com

The Poetry Collections

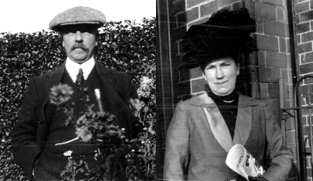

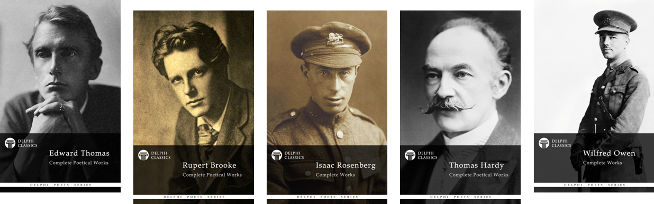

Plas Wilmot, Weston Lane, near Oswestry in Shropshire Owens birthplace

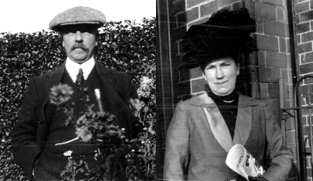

Owens parents, c. 1914

POEMS, 1920

Regarded by many critics as the greatest of the War poets, Wilfred Owen created a brief body of poetry that would change the publics perception of war. Previously poets depicted war as a patriotic and grand affair, full of noble deeds and great adventures. But it was the work of Owen and other poets like Siegfried Sassoon that brought home the true nature of war, including the horrors of trench and gas warfare, as well as the sensitive portrayal of the soldiers experiences of war.

Born to a middle-class family, Owen grew up in Oswestry in Shropshire, on the border between Wales and England. He was interested in poetry from a young age, particularly cherishing the works of Keats and Shelley. Owen had been writing poetry himself for some years before the outbreak of war in 1914 and he later wrote that his poetic beginnings originated from a visit to Broxton by the Hill, when he was ten years old. Undoubtedly the Romantic poets had the greatest influence on the style of Owens early poetry.

On 21 October 1915, Owen enlisted in the Artists Rifles Officers Training Corps. For the next seven months, he trained at the Hare Hall Camp in Essex. On 4 June 1916 he was commissioned as a second lieutenant in the Manchester Regiment. Starting the war as an optimistic young man, he was to change drastically in character forever, mostly due to two traumatic experiences. Firstly, he was blown high into the air by a trench mortar, landing among the remains of a fellow officer; and secondly, he became trapped for several days in an old German dugout. Following these two events, Owen was diagnosed as suffering from shell shock and sent to Craiglockhart War Hospital in Edinburgh for treatment. It was while recuperating at Craiglockhart that he met his fellow poet Siegfried Sassoon, which encounter would result in changing the course of Owens life and writing.

Sassoon had a profound effect on the young soldiers poetic voice and some of Owens most celebrated poems, including Dulce et Decorum Est and Anthem for Doomed Youth, were directly affected by Sassoons influence. Many manuscript copies of the poems survive, which are clearly annotated in Sassoons handwriting. Owen was always in awe of his older friend, once writing to his mother that he was not worthy to light Sassoons pipe. Nevertheless, Owens poetry would eventually be more widely acclaimed than that of his mentor.

Owens poetry underwent significant changes in 1917. His doctor at Craiglockhart, Arthur Brock, encouraged the young poet to translate his experiences in writing, specifically the horrors he relived in his dreams. Sassoon, who was influenced by Freudian psychoanalysis, also encouraged Owen to include satire and a more graphic use of language and realism. Owen was intrigued with the concept of writing from experience, entirely contrary to his previous romantic style. But where Owen advances further than many of the other war poets, perhaps even Sassoon himself, was not only his depiction of the gritty realism of war, but also his sympathetic portrayal of the soldiers experiences. He created a poetic synthesis of potent imagery and sensitive thought, creating a style of war poetry that was unprecedented and rich in depth.

In July 1918, Owen returned to active service in France, although he could have remained on home-duty indefinitely. His decision was almost wholly the result of Sassoons being sent back to England, after being shot in the head in a friendly fire incident and put on sick-leave for the remaining duration of the war. Owen saw it as his patriotic duty to take Sassoons place at the front and continue to write about the horrific realities of the war experienced by the soldiers. Sassoon was violently opposed to Owen returning to the trenches, threatening to stab him in the leg if he attempted to go. Aware of his attitude, Owen left for France in secret. Tragically, he was killed in action on 4 November 1918 during the crossing of the SambreOise Canal, exactly one week before the signing of the Armistice and was promoted to the rank of Lieutenant the day after his death. His mother received the telegram informing her of his death on Armistice Day, as the church bells were ringing out in celebration.

Preserving Owens works from obscurity, Sassoon was directly responsible for promoting his poetry after the war. Sassoon edited Owens manuscripts and was instrumental in the making of Owen as a great poet. Only five of Owens poems were published before his death, with one in fragmentary form. In 1920, Sassoon published, with an introduction by himself, the following collection of Owens poetry, featuring 18 of his most accomplished poems.

Almost all of the poems for which Owen is now chiefly remembered were written in a creative burst between August 1917 and September 1918. His self-appointed task was to speak for the men in his care, to show the Pity of War, and, in a preface he wrote shortly before his death, he explains that the pity is in the poetry.

Next page