SIEGFRIED SASSOON

Also by Jean Moorcroft Wilson

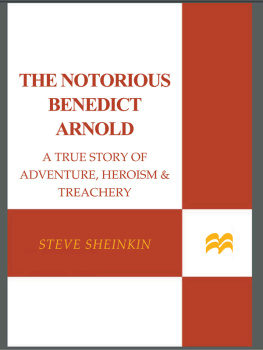

SIEGFRIED SASSOON:

The Making of a War Poet

SIEGFRIED SASSOON:

The Journey from the Trenches

ISAAC ROSENBERG:

Poet and Painter

ISAAC ROSENBERG:

The Making of a Great War Poet

I WAS AN ENGLISH POET:

A Critical Biography of Sir William Watson

CHARLES HAMILTON SORLEY:

A Biography

VIRGINIA WOOLF, LIFE AND LONDON:

Bloomsbury & Beyond

ISAAC ROSENBERG:

The Making of a Great War Poet

SIEGFRIED SASSOON

Soldier, Poet, Lover, Friend

Jean Moorcroft Wilson

Duckworth Overlook

This eBook edition 2013

First published in the UK and the US in 2013 by

Duckworth Overlook

LONDON

30 Calvin Steet, London E1 6NW

T: 020 7490 7300

E:

www.ducknet.co.uk

For bulk and special sales please contact

,

or write to us at the above address.

NEW YORK

141 Wooster Street

New York, NY 10012

www.overlookpress.com

2013 by Jean Moorcroft Wilson

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher.

The right of Jean Moorcroft Wilson to be identified as the Author of the Work has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available from the Library of Congress

ISBNs

Hardback: 978-0-7156-3389-2

Kindle: 978-0-7156-4876-6

ePub: 978-0-7156-4877-3

Library PDF: 978-0-7156-4878-0

Book design and formatting by Ray Davies

Manufactured in Great Britain by

CPI Group (UK) Ltd, Croydon, Surrey

Contents

For my brother, Findlay Wilson

and my husband, Cecil Woolf.

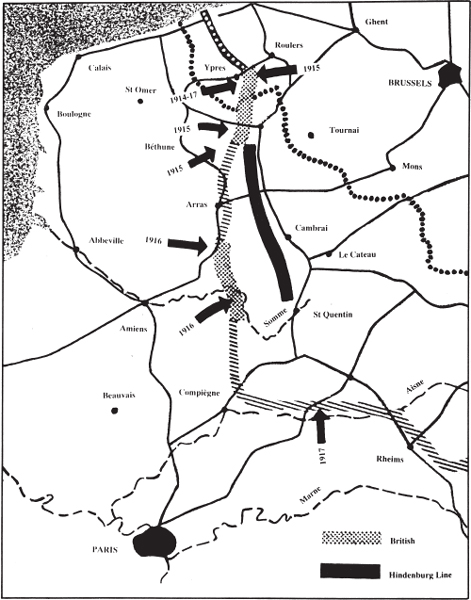

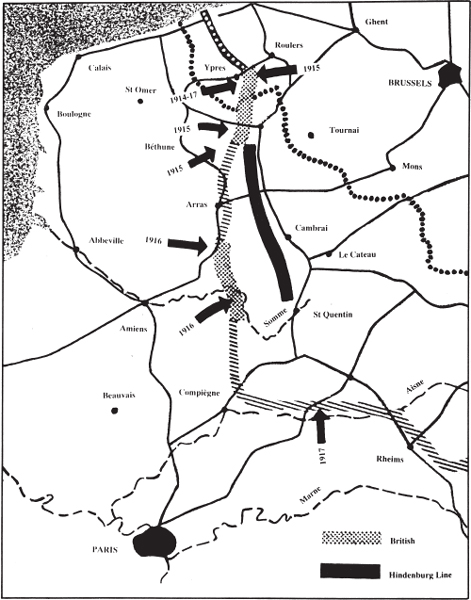

Part of the Western Front in Belgium and France (1915-17).

List of Illustrations

Introduction

F ew biographers are able to revisit past work and add the new material which often surfaces as a result of the original publication. So I consider myself fortunate in being given the chance to add significant fresh information to this new one-volume account of Siegfried Sassoons life, including unpublished poems from a 1916 trench journal and shocking evidence of Allied atrocities in the First World War. Sassoons draft of Atrocities, where the narrator congratulates a soldier on butcher[ing] some Saxon prisoners and confesses to lov[ing] to hear how Germans die is horrifying enough in itself, but the letter to C.K. Ogden accompanying it reveals how restrained Sassoon was in his published accounts of the War. Only the other day he tells the editor of the pacifist Cambridge Magazine from incarceration in Craiglockhart Hospital on 12 November 1917, an officer of a Scotch regiment (one of the many lead-swinging cases here) had regaled him with stories of how his chaps put bombs in prisoners pockets and then shoved them into shell-holes full of water. I was also able to study a previously buried notebook from the 1920s containing over thirty drafts of hitherto unknown poems.

*

A century has passed since the outbreak of the First World War, but the interest in Sassoon continues to grow. Dame Felicitas Corrigan, who admired him greatly both as a man and writer, summarised the extent of his significance when she wrote to him in 1966, the year before his death: To me you are a twentieth century portent: you have summed up in your personal experience the war-tortured, spiritually-bewildered, forsaken and blindly-seeking men of our times. A similar claim can now be made for Sassoons status in the twenty-first century. While still symbolizing for many all the heroisms and horrors of the Great War, he has also come to represent the craving for both sexual and spiritual fulfilment which marks our increasingly complex civilization.

More than any other figure from that period, with the possible exception of Rupert Brooke, however, Sassoon has become the prototype of the brave young soldier-poet, a serving officer who entered the war ready to lay down his life for his men and country. His courageous public protest about the handling of the conflict, once he encountered it at first hand, does not quite fit the stereotype, but his qualifications for the role in almost every other respect are impeccable. He came from the right social background: though half-Jewish, his paternal relatives were wealthy merchant princes, who hobnobbed with King Edward VII, and his maternal ones well-known sculptors, painters and engineers. He had received the correct education at Marlborough and Cambridge, though he did poorly at both. He was an officer adored by his men. Moreover, he was a conspicuously brave officer, awarded an M.C. for bringing in his wounded Corporal under intense fire in May 1916, and involved in several other daring raids. Finally, like Brooke who died before he could qualify fully for the role, Sassoon was extremely handsome, an inestimable advantage for iconhood.

The one condition Sassoon failed to satisfy was that he did not die in the war, though he told Charles Causeley as late as 1952 that most people thought he had.

It is as a war poet, however, that Sassoon will be remembered. Yet the importance of his life goes far beyond that, throwing light on a significant segment of the twentieth-century cultural world. Before and during the First World War he was a close friend of well-known patrons of the day, such as Edmund Gosse, Edward Marsh, Ottoline Morrell and Robbie Ross. He also knew a number of the war poets intimately Robert Graves, Robert Nichols and Wilfred Owen and exercised a palpable influence on all three. Though Charles Hamilton Sorley died before he had a chance to meet him, Sassoon recognized his fellow-Marlburians power. Then, after the war, he helped to promote the work of another outstanding but neglected war poet, Isaac Rosenberg. He also became a lifelong friend of Edmund Blunden.

In the years following the war Sassoon got to know many other writers, including Thomas Hardy, H.G. Wells, Arnold Bennett, Walter de la Mare, Max Beerbohm, T.H. White and Edith and Osbert Sitwell. He was a prolific letter-writer many of his missives, as T.H. White points out, being small works of art in themselves and his correspondence with some of the greatest names of the day adds immeasurably to our knowledge of them. A study of his life is a study of his age.

Sassoon himself wrote three volumes of autobiography, but because of the legislation outlawing homosexuality (in effect) during his lifetime, was never able to write the much franker book he had envisaged in 1921:

It is to be one of the stepping-stones across the raging (or lethargic) river

Fortunately, Sassoon did leave his diaries, which give a much clearer picture of him. However, though it is now possible to write relatively freely about his sexuality, it is virtually impossible in our less restrictive age to convey the problems he faced in a society which forbade him full expression of what he called his temperament.

In this and in many other respects, Sassoon is a difficult person to pin down. His was a particularly complex character, more contradictory than most. Perhaps because he came from two very different backgrounds, he seemed to be pulling in opposite directions most of his life. On the one hand there was the hearty extrovert, Mad Jack, physically daring, even bloodthirsty at times; on the other a timid, hypersensitive introvert with strong spiritual needs. Known as a great warrior, he nevertheless spent less than a month at the Front. He could write an almost completely autobiographical account of just one side of his personality,