Contents

Text 2018 by Marc Dierikx

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

This book may be purchased for educational, business, or sales promotional use. For information, please write: Special Markets Department, Smithsonian Books, P.O. Box 37012, MRC 513, Washington, DC 20013.

Published by Smithsonian Books

Director: Carolyn Gleason

Senior Editor: Christina Wiginton

Editors: Duke Johns and Gregory McNamee

Designer: Jody Billert

Cover design: Bart van den Tooren

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Dierikx, M. L. J., author.

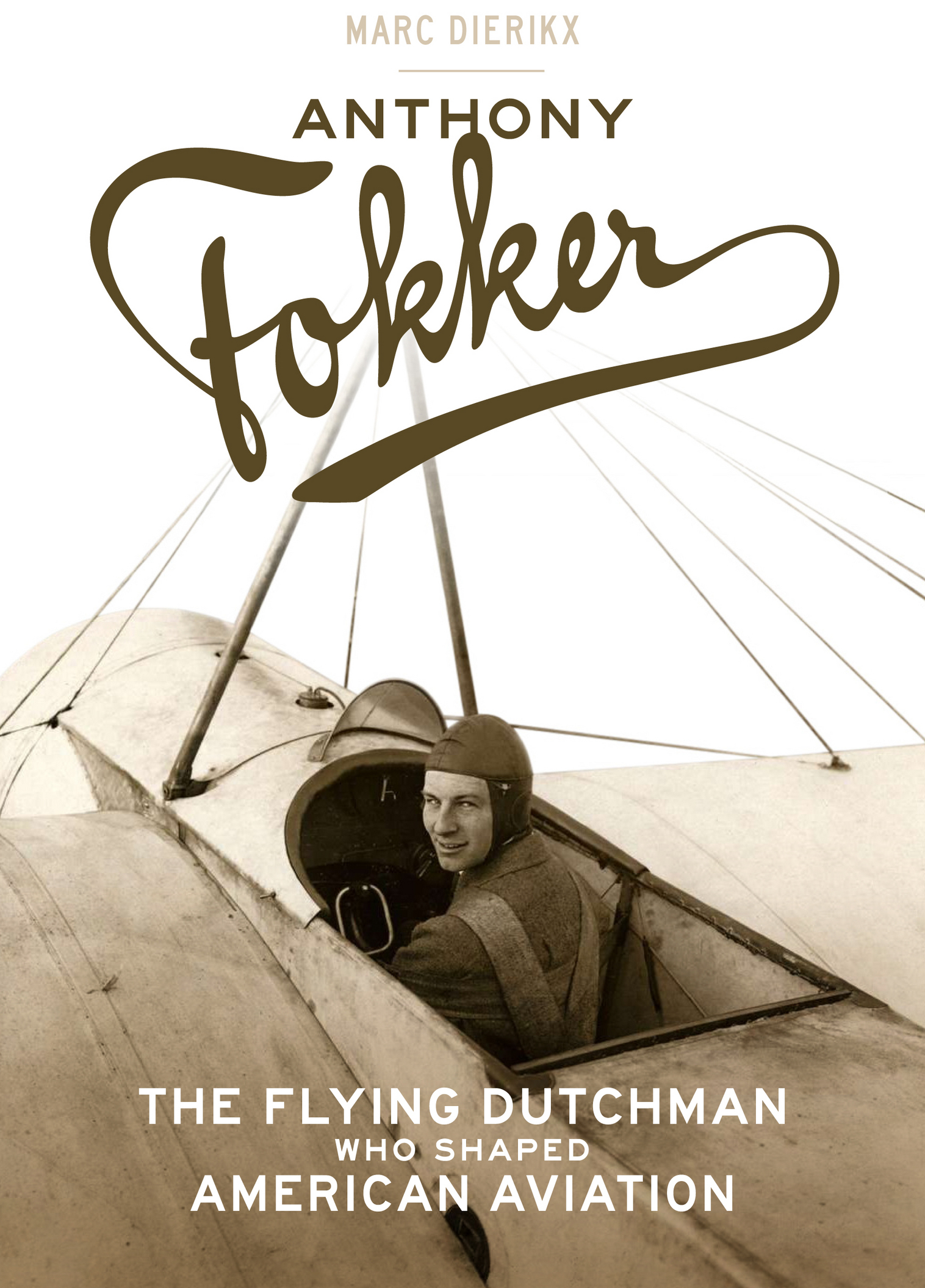

Title: Anthony Fokker : the Flying Dutchman who shaped American aviation / Marc Dierikx.

Other titles: Anthony Fokker. English | Flying Dutchman who shaped American aviation

Description: Washington, DC : Smithsonian Books, [2018] | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2017034700 (print) | LCCN 2017050282 (ebook) | ISBN 9781588346162 (eBook) | ISBN 9781588346155 (hardcover) | ISBN 1588346153 (hardcover)

Subjects: LCSH: Fokker, Anthony H. G. (Anthony Herman Gerard), 18901939Chronology. | Fokker, Anthony H. G. (Anthony Herman Gerard), 18901939Influence. | Air pilotsNetherlandsBiography. | Aeronautical engineersNetherlandsBiography. | Aircraft industryUnited StatesHistoryChronology.

Classification: LCC TL540.F6 (ebook) | LCC TL540.F6 D5313 2018 (print) | DDC 338.7/62913334092 [B]dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017034700

Ebook ISBN9781588346162

For permission to reproduce illustrations appearing in this book, please correspond directly with the owners of the works, as listed in the individual captions. Smithsonian Books does not retain reproduction rights for these images individually or maintain a file of addresses for sources.

v5.2

a

NEW YORK, NEW YORK

DECEMBER 1939

Among the shopping public, the heavyset, middle-aged man wearing his suit in a state of disarray, an advancing baldness hidden under the brim of his hat, does not immediately stand out. That this is the worlds first aviation multimillionaire is not apparent by sight. The streets are busy in New York this first day of December 1939. Although the war in Europenow three months oldis far away, New Yorkers hasten to department stores such as Saks Fifth Avenue and John Wanamaker. For weeks they have been luring customers with advertisements that this may well be the last time they stock imported luxury items. Expectations are that the Christmas sales will be 10 percent higher than in 1938.Fiorello La Guardia has announced special precautions to supply Manhattans trees and plants with extra watersomething normally done only in the heat of summer.

La Guardia, nicknamed the little flower after his first name, has an eye for nature. Since his appointment as mayor almost six years ago, he has had Central Park restructured and replanted. And it is not just flowers and plants that he loves. As an aviation enthusiast, former pilot, and bomber commander in the Great War, he is also the driving force behind the creation of a new airport. After two years of construction and $40 million in costs, this is his big day: at three minutes past midnight he is to welcome the first scheduled airlinera flight from Chicago.of aviation have been invited to witness the event. Among this select group is Anthony Fokker.

It is already past midday when the porter opens the door of the former Viceroy Hotel at Park Avenue and 59th Street for Fokker. In the luxurious hallway, where marble and gold glisten in the lamplight, his appearance seems slightly incongruous. Yet he feels at ease in this environment. He knows the building, although it has changed much since its grand opening in 1929. In the wake of the Great Depression, the owners reconditioned the thirty-two-story building. Its 525 rooms have been made into apartments to be sold individually. What has not been sold has been leased. Even Delmonicos, a well-known specialty restaurant once frequented by wealthy New Yorkers, is no more.

It is quiet in the hallway when Fokker reports to the reception desk. In his somewhat awkward, Dutch-riddled English, he tells the receptionist he has come for his appointment with doctor Robert Cushing. In anticipation of the gathering at the airport this evening, he has traveled from his house in Nyack in upstate New York to seek release from his persistent splitting headaches. From the lovely village on the southern bank of the Hudson River, the drive to Manhattan has taken some forty-five minutes. The road through the rolling, wooded landscape high above the river is well known to him. Since moving into his mansion Undercliff Manor in the summer of 1937, he has often driven this route. His old house in the woods near Alpine appears unchanged as he passes. At Brookside Cemetery, just outside Englewood, New Jersey, much has remained the same as well; from the road he can see Violets grave on the high grounds, where he buried his second wife after she met such a tragic death. He has driven here hundreds of times, when he still had his factories at the Teterboro Airport and in nearby Passaic, New Jersey. His German companies closed long before. Only the Dutch factory is left, far away in Amsterdam. He interferes with it as little as possible and prefers to spend his time on one of his boats.

Outside Englewood, Fokker turns left across the new George Washington Bridge that leads to New York. From the high bridge he can see Riverside Drive with his former apartment on the corner of 101st Street, which he abandoned after his wifes death in 1929.

He arrives late for his appointment with Dr. Cushing. Being late is something Anthony Fokker relishesthe prerogative of an homme arriv. Even President Warren Harding had to wait thirty minutes for him at the White House seventeen years ago. There is no need to rush anyway: Cushing has seen him often enough. His ailment has been the same for years: chronic sinusitis, a condition he has picked up after many years of flying in open cockpits. Today his face is again taut. Breathing through the nose exhausts him. It almost appears as if the congestion in his forehead presses on his eyes more than usual. His whole head feels heavy, and even his neck is rigid.

Doctor Cushings practice is pleasantly light and spacious. Its low-slung sofa suggests an ordinary living room rather than a doctors office. This is no coincidence; Cushing caters to an affluent clientele and wants his patients to feel at ease. His specialty, osteopathy, is a relatively new, alternative treatment in 1939, aimed at providing relief for patients suffering from reduced flexibility of body tissues and bone structure. The treatment involves special manual techniques.