ALSO BY HARRY KESSLER

Notizen ber Mexiko

Walther Rathenau: His Life and Work

Gesammelte Schriften, eds. Cornelia Blasberg and Gerhard Schuster

Das Tagebuch: 18801937, eds. Roland S. Kamzelak and Ulrich Ott

(in nine volumes)

Also by Laird Easton

The Red Count: The Life and Times of Harry Kessler

THIS IS A BORZOI BOOK

PUBLISHED BY ALFRED A. KNOPF

Copyright 2011 by Laird Easton

All rights reserved. Published in the United States by Alfred A. Knopf, a division of Random House, Inc., New York, and in Canada by Random House of Canada Limited, Toronto.

www.aaknopf.com

Knopf, Borzoi Books, and the colophon are registered trademarks of Random House, Inc.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Kessler, Harry, Graf, 18681937.

[Tagebuch, 18801937. English. Selections]

Journey to the abyss : the diaries of Count Harry Kessler, 18801918 / by Harry Kessler ; edited and translated, and with an introduction by, Laird M. Easton.1st ed.

p. cm.

This is a Borzoi bookT.p. verso.

A selection of the early diaries, 18801918, of Count Harry Kessler, translated into English for the first time.

Includes index.

eISBN: 978-0-307-70148-0

1. Kessler, Harry, Graf, 18681937Diaries. 2. Kessler, Harry, Graf, 18681937Childhood and youth. 3. IntellectualsGermanyDiaries. 4. DiplomatsGermanyDiaries. 5. GermanyHistory18711918Sources. 6. GermanyPolitics and government18881918Sources. 7. GermanyIntellectual life20th centurySources. 8. EuropeIntellectual life20th centurySources. 9. Elite (Social sciences)GermanyHistory20th centurySources. 10. World War, 19141918Personal narratives, German.

I. Easton, Laird McLeod, [date] II. Title. DD 231. K 4 A 3 2011 943.084092dc22 [ B ] 2011013585

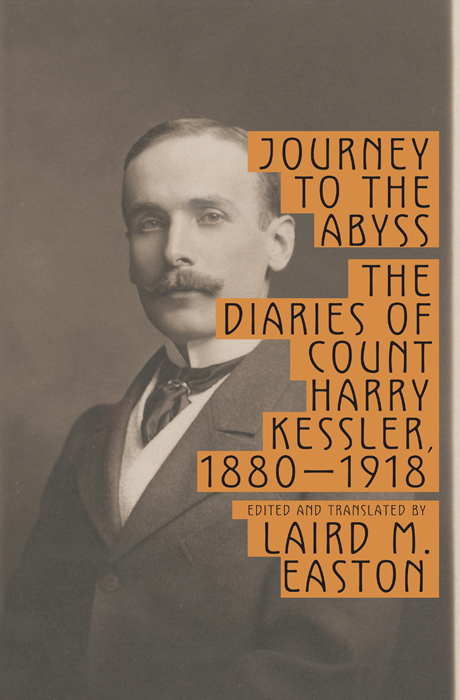

Jacket photograph Klassik-Stiftung Weimar/Fotothek

Jacket design by Peter Mendelsund

v3.1_r1

I dedicate this translation to my daughter,

Natasha N. Easton

Contents

Acknowledgments

My first debt of gratitude is to the German Literary Archives in Marbach am Neckar and especially to the dedicated scholars under the direction of Roland S. Kamzelak and Ulrich Ott who are producing the definitive German edition of the diaries. Without their magnificent work, I could not have undertaken this translation. I am also deeply grateful to the National Endowment for the Humanities for the fellowship in 200708 as well as to California State University, Chico, for the yearlong sabbatical that enabled me to finish the book. I would like to thank my agent Steve Wasserman, my editor Shelley Wanger, both fanatics de Kessler, her assistant Ken Schneider, Kevin Bourke, and, for critical assistance at one point, Professors David Blackbourn of Harvard University and James J. Sheehan of Stanford University. Needless to say I am responsible for all errors and infelicities. To my family, who once again had to endure the consequences of my prolonged immersion in this work, I offer my heartfelt thanks.

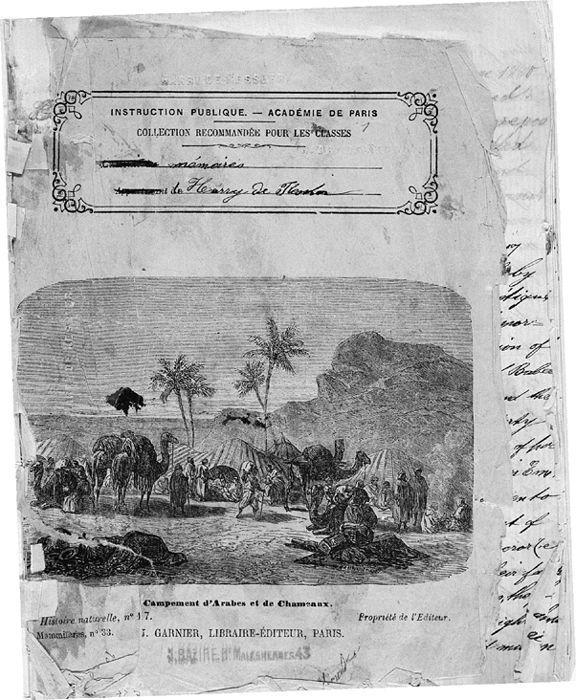

The cover of Harry Kesslers first diary, begun June 1880 when he was twelve ()

Introduction

You will write the memoirs of our time.

DEHMEL TO KESSLER , September 5, 1901

On August 18, 1918, in the middle of the most decisive month of the First World War, Count Harry Kessler took a brief respite from his activities as a cultural attach, diplomat, and secret agent. He was fifty years old, and the stress of the war, much of which he had witnessed in person on the Western and Eastern Fronts, had taken its toll. On his birthday back in May, as he lay sick and exhausted in bed, he had written in his diary, I have often thought how pleasant and basically indifferent a thing it would be to slide slowly and painlessly into the eternal unconsciousness. Now he took the train from Berlin, the center of the maelstrom with its intrigues and its anxieties, and returned to his house in Weimar, which he had not visited for years. His coachman was waiting for him at the station, and his dog greeted him joyously:

In an almost miraculous way my house seemed unchanged after all the eventful years: youthful and bright late in the evening under glowing lights, awoken like Sleeping Beauty. The impressionist and neo-impressionist paintings, the rows of books in French, English, Italian, Greek, and German, Maillols figures, his somewhat too fat, lusty women, his beautiful naked youth modeled after the little Colinas if it were still 1913 and the many people who were here and are now dead, missing, scattered, enemies, could return and begin European life anew. It seemed to me like a little palace out of A Thousand and One Nights, full of all kinds of treasures and half-faded symbols and memories, which someone from another age could only nibble at. I found a dedication from DAnnunzio; Persian cigarettes from Isphahan brought by Claude Anet; the bonbonnire from the baptism of the youngest child of Maurice Denis; a program of the Russian Ballet from 1911 with pictures of Nijinsky; the secret book by Lord Lovelace, the grandchild of Byron, about his incest, sent to me by Julia Ward; books by Oscar Wilde and Alfred Douglas with a letter from Ross; andstill unpackedRobert de Montesquious comic-serious masterpiece from the years before the war about the beautiful Countess of Castiglione whom he affected to love posthumouslyher nightshirt lay in a jewel case or little glass coffin in one of his reception rooms.

What a monstrous fate emerged from out of this European lifeprecisely out of itjust like the second-bloodiest tragedy of history arose from playing at shepherds and from the light spirit of Boucher and Voltaire. We all actually knew, but didnt know at the same time, that the age was heading not toward a lasting peace but toward war. It was a kind of floating feeling like a soap bubble that suddenly burst and disappeared without a trace when the hellish forces, which were fermenting in its lap, were ripe.

Kesslers trope is familiar. Caught up in the unforeseen cataclysm, we look back on the period before as an island of luxe, calme et volupt, yet also see it in hindsight as hastening toward its own destruction. For Europeans this was how the modern history began, with Marie Antoinette and the rest of the French court playing shepherd and shepherdess in Versailles before being swept away by the revolution. It was the natural comparison for Kessler, who had often reflected on the meaning and consequences of the French Revolution. Yet he now knew that the First World War would serve as a new historical watershed. And the Belle poque that his art and books in Weimar evoked would be seen as a period of febrile cultural fermentation, doomed to destruction, a doom intuited unconsciously by those who experienced it.

But it was not just a good story, chosen by Kessler because it echoed familiar themes, any more than history is, in the end, merely a fiction we choose because of its aesthetic coherence. It corresponded to his lived experience. The proof for this is the extraordinary document he left behind as his greatest work, fifty-six years of journals, chronicling his life led at the center of European art, literature, and politics during the greatest cultural and political transformations in modern history.