This book is dedicated with great appreciation (and affection) to Jonathan Dyer and Diane Holmes, without whom it wouldnt exist. Their months of hard work and dedication are a tribute to the men whose stories they have helped to tell.

And in memory of Brian Holmes (19402016)

At The History Press: Sophie Bradshaw and editors; Victoria Wallace, Andrew Fetherston and Liz Woodfield at the Commonwealth War Graves Commission; Rugby School; Cheryl Sadana; Sarah Warren-MacMillan in School Library, along with the other library ladies: Shirley, Emily and Simo and also Lucy Gwynn in College Library, all at Eton College. Thanks is also due to College Library for use of the Macnaghten Library and Peter Devitt at the Royal Air Force Museum, Hendon.

The families of those included in the book: Stuart Disbrey, Jack Cowdy, William Hallidie-Smith, Miranda Pender, Vivian Sheffield, Jan Stephens, Edgar Lloyd, Robert Matthewson, Hazel Effie Morris and Kirk Butt, Muriel Chislett, Natasha Legge and the kind people of Robinsons Newfoundland for helping us to find her, Reverend William Hepper and the late Mr. F. Nigel Hepper, Lindsay Harford and Sarah Rhodes.

Kim Downie at the Unviersity of Aberdeen; Chris Edwards at St Edwards School, Oxford; Dee Murphy at Rugby School; Sally Todd at St Johns School Leatherhead; Upper Canada College, Toronto. Ryno Human of Remember Us South Africa (@rememberussa) and Lieutenant Klehnhans of the South African Defence Force Documentation Centre.

The entry for William Dexter would not have been possible without the World War Zoo blog produced by Mark Norris at Exeter Zoo and information provided to them for their William Dexter biography by ZSL London Zoo.

Both the Australian National War memorial and the Long Long Trail have been valuable online resources, as has Len Ashworth at the Lithgow Mercury , NSW; David Tulip at The Channel Heritage Centre, Margate, Tasmania; Lord Astor of Hever, Tom Donovan; and Rutland Remembers.

For help in India and Pakistan: Kamal Hyder and the staff at the Islamabad Bureau of Al Jazeera English and Ali Abbas Zafar.

Joshua Levine, Paul Reed and Peter Hart variously for their yoda-like presence and support, advice, assistance with maps and loan of their material, Alice and Tim Holmes, The La Boisselle Study Group, Simon Jones for his patience and generosity in helping with our tunnellers and Roger Stillman Photography for helping to digitally enhance some of our aged photographs.

Every effort has been made to trace copyright holders and to obtain their permission for the use of copyright material. We apologise for any errors or omissions and would be grateful if notified of any corrections that should be incorporated in future reprints or editions of this book.

AC: My sister, Karen Halls for multitasking as PA, personal motivator and human shredder, not to mention helping to save the manuscript for October from rattling round Newcastle on an empty football train. Work Husband Naz, for spreadsheet services and various other members of House Lannister: Paulbot Fernandes, Nathan, Nathans Beard, Biggles and Mike for picking up the slack on occasion so I could get this done! Stamford Bridges answer to Scott Tracy, you know who you are!

AH: Diane and Adam, not only for their contributions to the research, but for months of patience and support whilst we got this done and for making the battlefield trips all the more enjoyable.

JD: Jules and Lana, all I ever wanted; my father, David Dyer for passing on his love of history; Alex and Andrew, for having me along and not sparing the unicorns and Paul Kempton; you must come on a battlefield trip one day!

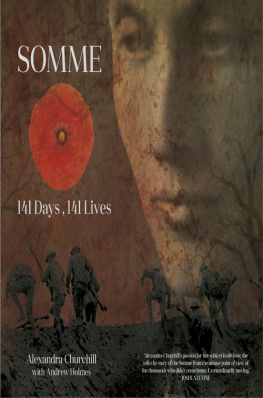

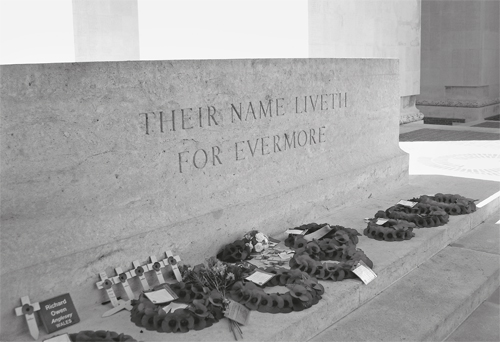

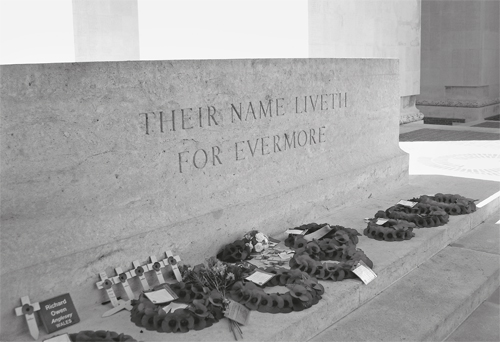

Poppy tributes placed beneath thousands of names carved into the Thiepval Memorial to the Missing on the Somme. (Alexandra Churchill)

The Somme battlefield, 1916.

CONTENTS

A hundred years ago on the Western Front. On 30th June 1916, professional soldiers were lining up to go into battle alongside miners, farmers, labourers, clerks, accountants; men drawn from every walk of life. They assembled in lines with boys who had only just walked from their schools into the army. Gathered from the length and breadth of Britain, and her dominions, tens of thousands were assembled in Picardy to embark upon the most ambitious offensive the British Army had ever undertaken.

The year 1915 had not been a good one. British attacks in France and Belgium had been, for the most part, bloody failures. At the end of the year the BEF underwent a change of command and Douglas Haig was placed in charge. It was not only on his front that things looked bleak. In the East the Central Powers had shoved back the Russians in force. Italy was struggling against the Austro-Hungarian army in alpine terrain. Bulgaria had entered the war on the side of Germany and Serbia was in utter turmoil. Evacuation was about to prove the humiliating culmination to the campaign in the Dardanelles, Kut was under siege in Mesopotamia after any initial success had come to nothing and British East Africa was also under threat.

It was clear that the Allies, in their many different theatres of war, needed to organise and mount a coherent, joint attack against Germany and her allies. By mid-February it had been agreed that a combined offensive would proceed round about the beginning of July and would be the main attempt at defeating the enemy on the Western Front in 1916. Before this, the British would extend their line south, taking over more territory from the French.

But all Allied planning was thrown into disarray at the end of February when the Germans began their own brutal offensive against the French at Verdun. By the 26th the situation had been acknowledged as potentially catastrophic. They begged their allies on all fronts to keep the enemy busy to prevent as many German troops as possible from being fed into the battle and asked the British to make diversionary attacks elsewhere along the lines to take German focus away from Verdun. Casualties grew towards a quarter of a million. Justifiably, although they still planned to co-operate, the summer offensive had taken a step backwards in terms of where the French would be able to deploy their resources in the summer of 1916.

Thus the British Army, by circumstance, had now assumed the greater part of the responsibility for the offensive campaign on the Western Front. It was feared that the most that could be expected of the French, was that if a breakthrough was made they would try and help exploit it. At the end of May there was even a concern that the British Army might have to attack without any contribution from France at all, so badly had Verdun consumed their allys resources. The summer battle was now ostensibly going to be fought to take pressure off the French.

The official history postured that the reason the French, who were ever-convinced that the British were not contributing their fair share, suggested the Somme right next to Haigs front was that it meant his force would be bound to take part in it. Until 1916 it had been a quiet sector. In terms of fighting, nothing of great significance had taken place since the French and Germans began digging in in 1914. Joffre could argue that the terrain was advantageous, but unlike, say, Neuve Chapelle, which ultimately had the strategic prize of Lille behind it; there was nothing of consequence by comparison on the Somme, no gain beyond the German line that would cause the enemy to collapse.

Next page