Introduction and Acknowledgments

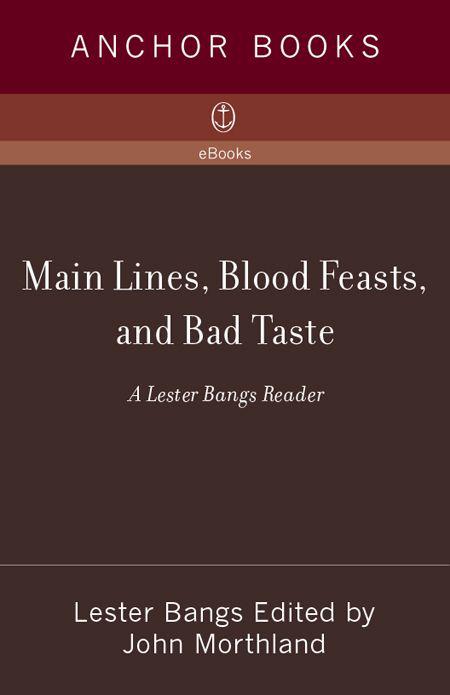

T hough I loved and respected his writing as much as anyone, when Lester Bangs died, basically of a Darvon overdose, in 1982 I mourned the loss of a great friend more than that of a great writer. Truth is, I never read his work critically; I liked what I liked and if something else he wrote didnt engage me, I just moved along to the next thing without giving it much thought. Hardly a day has passed since that I havent thought of Lester, but the hole his death left in my personal life dwarfs the loss I feel as a reader and colleague of Lester.

Yet here I have been these last few months, reading him very critically, making judgments right and left while agonizing to determine what I considered most worthy of inclusion in this book that hadnt already appeared in Psychotic Reactions and Carburetor Dung (Alfred A. Knopf, 1987), the posthumous anthology Greil Marcus edited. I wish I could now give you the magic formula I used, but there isnt one; it's a highly subjective matter, after all. I tried to pick the best-written pieces that I felt reflected the range of Lester's themesmake that, his passionsand I tried to group and order them in a way that created a feel rather than a timeline (Greil having already done the latter so well). In the process, I rediscovered, for me, two key points about his work.

The first was his ability to move his most electric thoughts from the brain to the page without interruption. As a music writer myself, Ive heard great improvisational players declare that when theyre at their best, they dont create music so much as music passes through them and out their instrument. Having shared an office with Lester, I can remember sitting there in awe, watching him write, literally, as fast as he could type. Of course, this sometimes created inferior as well as superlative work, and of course, I can also picture him (albeit less frequently) slumped head down on typewriter, trying to think of what to say next, and how to bend the language to his will. But surely this ability accounts for the sheer rollin-and-tumblin energy of his work. It also explains how he could write such a delightfully scathing putdown of an album, such as the MC5 review that appears in this book, only to decide later that the same LP is an all-time classic, and be equally credible both times; how he can use the same criteria to praise the Miles Davis of the Seventies that hed earlier used to condemn that very same music; that's also why he was so unselfconscious about making so many confident predictions that have, with time, turned out to be so wrong (plenty of them occur in these pages). And it's why I wanted to bunch together a few of his pieces involving travel; to my mind, some of his most spontaneous and explosive writing came when Lester was plopped down in a relatively new or foreign place and simply turned loose to record what he saw and heard. In that situation, his sense of wonder could elevate the obvious into revelation, translate the ordinary into the extraordinary, launch into amazing moral and ethical tangents, and find humor in the most serious places and/or a dark underbelly where humor was intended. And do it all so breathlessly it left a reader with jet lag.

The second point concerns how rock writing has changed since the days when these pieces were done. This subject is debated virtually any time two or more rock critics wind up in the same room, especially if theyre at an industry event like South By Southwest; the arguments usually revolve around the fact that there are so many more music writers than ever before; around the way it's become a recognized profession in such a short time, and geared, not coincidentally, toward consumerism and the music industry's notion of publicity rather than toward journalism and/or criticism; around how much more difficult it's become, and the concessions a writer has to make to the PR machine, to get face time with interview subjects; around how effortlessly music journalism mutated into celebrity journalism. These are all good and true insights, and Ive made them myself at various times, but the single factor that strikes me most after months of immersion in Lester's work is that rock critics dont fantasize these days. Period. Nuff said.

Nearly all the previously published writings collected here first appeared in publications that were outsideand often way outside the publishing mainstream at the time, and that mainstream has become even narrower since (to the extent that some of these pieces probably couldnt even get published in today's fringier periodicals). At the time of his death, after about thirteen years as a professional writer, Lester's name was known only in fairly small circles. Since then, as what's acceptable from a writer has come to be defined ever more conservatively, Lester's own stature has risen, proving once again that you dont miss your water til your well runs dry, and that the vision and value of troublesome types can seldom be celebrated until theyre no longer troublesome. He has been the subject of a biography and appeared in songs by artists such as R.E.M., Bob Seger, and the Ramones. I thought Philip Seymour Hoffman got Lester's tude, at least, down pretty well in Almost Famous, Cameron Crowe's paean to his own days as a young rock writer. Rock critics today routinely cite Lester as their greatest influence, though it's usually hard to detect said influence in their work.

All of this has, finally (and thankfully), made it possible for American culture to take Lester more seriously as a writer. But that's come at a price, and it's one that Lester himself often wrote about. The best-known, bull-in-a-china-shop Lesterwho was always dangerously loaded, who could be so insulting and malicious as well as self-destructive, who could be oblivious to the people around him, who was a Falstaffian clown and then grimly serious most of the timethe kind of guy, in short, some unfortunates like to live through vicariouslyhas stuck in the public fancy. The Lester who could stay up hours calmly giving or taking personal advice, who could be deferential and accommodating and even accept rebuke and try to act on it constructively who seemed neither doomed nor damned though certainly driven, who had an expansive lust for life and a sense of humor and (sometimes even, and for no apparent reason) cheerfulness to match it, who could actually be counted on, dammit, has become even more obscure than he was while alive. To some extent this is inevitable, especially in someone as contradictory and conflicted as Lester. And certainly nobody in his right mind could minimize the former Lester; he was there for everyone to see, is well documented in these pages, and did, make no mistake, manage to kill himself accidentally at age thirty-three. But if nothing else, I hope that making so much of his work available again will, in addition to reconfirming that he was one of the most worthy chroniclers of his times, illuminate once again the Lester who made a pretty good friend. And as long as he's receiving all this added recognition, Id like it to extend to his work again, too. Given that one of his pet themes concerns romanticizing, or reducing to their most colorful caricature, pop figures (especially those who die young) rather than looking harder at the totality of their lives and the work that brought them to prominence in the first place, it's the very least a book such as this should do. Especially for those readers who werent around at the time.