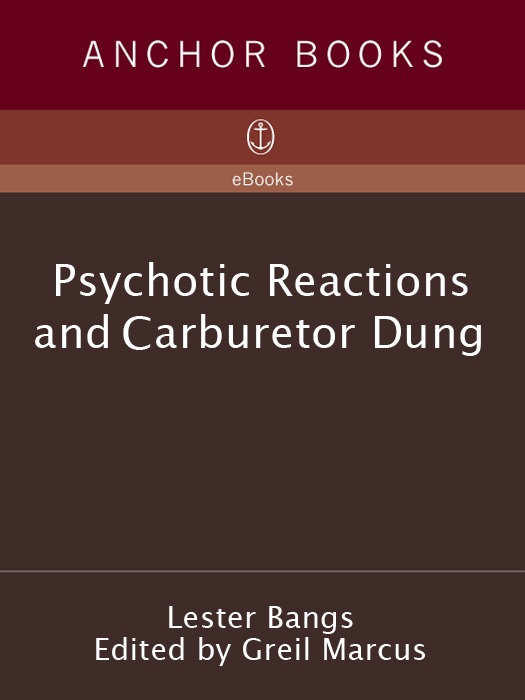

First Anchor Edition, January 2003

Copyright 1987 by The Estate of Lester Bangs

Introduction Copyright by Greil Marcus

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. Published in the United States by Random House, Inc., New York, and simultaneously in Canada by Random House of Canada Limited, Toronto. Originally published, in hardcover by Alfred A. Knopf, Inc., New York, in 1987, and subsequently in trade paperback by Vintage Books, a division of Random House, Inc., New York, in 1998.

Many of the essays in this work were originally published in Creem. Copyright 1970, 1971, 1972, 1973, 1974, 1975, 1986 by Creem. Reprinted by permission

Owing to limitations of space, all other acknowledgments for permission to reprint previously published material will be found in Acknowledgments.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Bangs, Lester.

Psychotic reactions and carburetor dung.

1. Rock musicHistory and criticism. I. Marcus,

Greil. II. Title.

ML3534.B315 1988 784.54009 88-40180

eISBN: 978-0-8041-5016-3

www.anchorbooks.com

v3.1

Contents

Introduction and

Acknowledgments

BIO: Lester Bangs was born in Escondido, California, in 1948. He grew up in El Cajon, California, which means The Box in Spanish, where he did things like wash dishes, sell womens casuals, and work as assistant for a husband-and-wife artificial-flower-arranging team while freelancing record reviews and pretending to go to college until 1971, when he moved to Detroit and went to work for Creem magazine. In the five years he worked there as head staff writer and in various editorial capacities, he defined a style of critical-journalism based on the sound and language of rock n roll which ended up influencing a whole generation of younger writers and perhaps musicians as well. In 1976 he quit Creem to move to New York City and freelance. Since then he has also led two rock n roll bands active on the Manhattan club scene, and began cutting records of his original rock n roll compositions (he writes lyrics, sings lead and plays harmonica, allowing that All my melodies are the same melody, and thats a blues), the first of which, Let It Blurt/Live, was released on the Spy label early in 1979. Presently he is preparing an album

So wrote Lester Bangs a year or two before he died in 1982. The fact of his death demands that any bio be more specific: he was born on 14 December 1948; he died on 30 April 1982, accidentally, due to respiratory and pulmonary complications brought on by flu and ingestion of Darvon. The name of the store where he sold womens casuals was Streichers Shoes, Mission Valley Shopping Center; his album was released in 1981 on the Live Wire label, credited to Lester Bangs and the Delinquents, under the title Juke Savages on the Brazos, though he also thought of calling it Jehovahs Witness, after the faith his mother embraced following the death of his father in 1955. Lester said it accounted for his approach as a rock critic, Frances Pelzman wrote me as work began on this book, because he was always trying to make converts. The fact of death also provokes idle speculation: of all the details he might have included in a one-paragraph autobiography, why did Lester mention that El Cajon means The Box? Was it because box is old hipster slang for record player, or because the name signified a confinement he thought he could never escape?

Its not easy to write about a dead friend without veering off into melodrama or sentimentality; melancholy might be the most honest tone, but its the hardest to catch. I should be making a case for the importance of Lester Bangss work, explaining precisely why those who did not know it in its time should read it, why that work will enrich the life of anyone willing to meet it even halfway on its own terms, and while I believe Lesters writing will do exactly that, I have no heart for the job. It seems condescending, both to the reader and to the writing; it pains me that Lester found it necessary to tout his work on the basis of its influence, real and even overwhelming as that influence was, rather than on the basis of its value. Another self-portrait, then, from about the same time as the first: I was obviously brilliant, a gifted artist, a sensitive male unafraid to let his vulnerabilities show, one of the few people who actually understood what was wrong with our culture and why it couldnt possibly have any future (a subject I talked about/gave impromptu free lessons on incessantly, especially when I was drunk, which was often, if not every night), a handsome motherfucker, good in bed though of course I was so blessed with wisdom beyond my years and gender that I knew this didnt even make any difference, I was fun, had a wild sense of humor, a truly unique and unpredictable individual, a performing rock n roll artist with a band of my own, perhaps a contender if not now then tomorrow for the title Best Writer in America (who was better? Bukowski? Burroughs? Hunter Thompson? Gimme a break. I was the best. I wrote almost nothing but record reviews, and not many of those. He was half-kidding until the parenthesis began (he never closed it); then he was telling the truth. Perhaps what this book demands from a reader is a willingness to accept that the best writer in America could write almost nothing but record reviews.

I dont really know about the claims preceding the parenthesis. Like thousands of other people, I knew Lester mostly through his writing. We were, perhaps, deep friends, but never close. I was his first editor, at Rolling Stone in 1969; after he left California for Detroit and New York, we saw one another half a dozen times, talked on the phone twice as often, corresponded twice more than that. We spoke often of my editing a book of his work; thus this one.

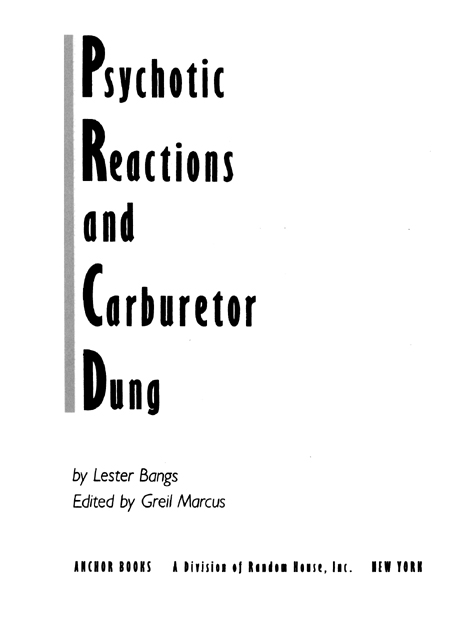

The first bio quoted above is from the manuscript of a collection of Lesters published pieces on rock n roll he prepared in 1980 or 1981. The only publication he had been able to secure had been through a German company, for publication only in German; the working title was Psychotic Reactions and Carburetor Dung. This is not that book, which never appeared, though the title is the same, the dedication is Lesters, and most of his selections and some of his section headings have been retained; an enormous amount of material has been added, much of it never published before. Lesters book was meant to merely sum up one period in what was to be a long and unpredictable career. (When Lester died, he was about to leave for Mexico to write a novel, All My Friends Are Hermits, though I dont for a minute believe, as some people far closer to Lester than I ever was have said, that he would have abandoned writing about music.) His book was not meant to define a legacy, which is what this book has to do.

Lester bought his first record (TV Action Jazz by Mundell Lowe and His All-Stars, RCA Camden) in 1958; from then on he devoured every piece of sound-bearing plastic he could find. My most memorable childhood fantasy, he once wrote, was to have a mansion with catacombs underneath containing, alphabetized in endless winding dimly-lit musty rows, every album ever released. About the same time, he became a constant reader; soon after, he became a teenage beatnik. Jack Kerouac and William Burroughs were his heroes and teachers; he bought their myths of dissipation and redemption, dope and satori. Their books and everyones records made him a writer.