JANE EYRE

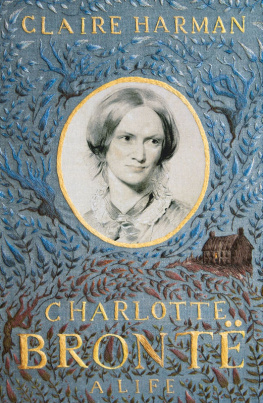

CHARLOTTE BRONT

JANE EYRE

With an Introduction and

Contemporary Criticism

Edited by JILL KRIEGEL

Ignatius Critical Editions Editor

JOSEPH PEARCE

IGNATIUS PRESS SAN FRANCISCO

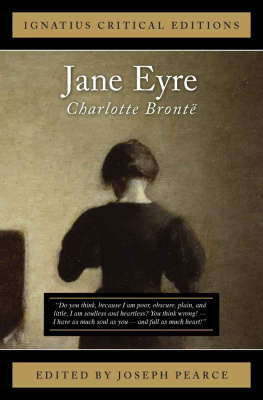

Cover art:

Interior

by Vilhelm Hammershoi

1898 (oil on canvas)

Nationalmuseum, Stockholm, Sweden / Bridgeman Images

Cover design by John Herreid

2014 by Ignatius Press, San Francisco

All rights reserved

ISBN 978-1-58617-699-0 (PB)

ISBN 978-1-68149-244-5 (E)

Library of Congress 2014905956

Printed in India

Tradition is the extension of Democracy through time; it is the proxy of the dead and the enfranchisement of the unborn.

Tradition may be defined as the extension of the franchise. Tradition means giving votes to the most obscure of all classes, our ancestors. It is the democracy of the dead. Tradition refuses to submit to the small and arrogant oligarchy of those who merely happen to be walking about. All democrats object to men being disqualified by the accident of birth; tradition objects to their being disqualified by the accident of death. Democracy tells us not to neglect a good mans opinion, even if he is our groom; tradition asks us not to neglect a good mans opinion, even if he is our father. I, at any rate, cannot separate the two ideas of democracy and tradition .

G. K. Chesterton

Ignatius Critical EditionsTradition-Oriented Criticism for a new generation

CONTENTS

Introduction: Helens Hour in Janes Journey: The Lasting Value of Morality in Charlotte Bronts Jane Eyre

Jill Kriegel

To Delight in Sacrifice: True Love in Jane Eyre

Dedra McDonald Birzer

Religion in Jane Eyre

Raimund Borgmeier

Jane Eyre : Reading the Writing on the Wall

Crystal Downing

Eyre of Rebellion?

Jeanette Amestoy Flood

Anatomy of a Hero: Redeeming a Catholic Rochester

Eleanor Bourg Nicholson

INTRODUCTION

Helens Hour in Janes Journey:

The Lasting Value of Morality in

Charlotte Bronts Jane Eyre

Jill Kriegel

St. Josephs Catholic School

Charlotte Bronts Jane Eyre a staple in the library of any lover of Victorian literature, as well as of countless high-school and college literature syllabiis among the most misread novels of the nineteenth century. In the hands of the feminist campaign, Jane becomes their abused and overused poster child, morphed from the truth-seeking young woman she is into a power-seeking, rage-filled woman. According to the postmodern agenda, this emerging young woman, whom Bront actually created with that element of fear which is one of the eternal ingredients of joy, is to be pitied for her fear and applauded when she (supposedly) spurns authority and abandons obedience. Contrary to the majority of Charlotte Bront study since the mid-twentieth century, no feminist reading, no postcolonial reading, can do justice to Janes journey in Jane Eyre , for hers is a universal voyage toward understanding, a journey that we may only understand as we acknowledge the author whose life pervades every page of her best-loved work.

Charlotte Bront was born in 1816, the third of six children to Reverend Patrick Bront and Maria Branwell. This family of literary childrenwith Charlotte, Emily, and Anne to become prominent names among Victorian novelistsgrew up in Yorkshire, specifically in the remote parish of Haworth, known for its polluted waters, and thus known for its shorter than usual life expectancy. This fact of early death, as we will see, plays a key factor both in Charlotte Bronts own life and in that of her semi-autobiographical heroine, Jane. As parallel as the sanitary conditions of Haworth and Janes second home at Lowood are, perhaps even more profound are the parallel characters of Haworths citizens and young Jane. According to Bronts friend and preeminent biographer, Elizabeth Gaskell, these Yorkshiremen are known for enduring grudges,... once lovers or haters, it is difficult to change their feeling. Janes bildungsroman is not one of a woman who achieves her long-awaited goals of superiority and dominance, but rather of a woman who relishes her hard-earned, hard-learned blessings of sanctity and reverence.

To do Bronts Jane Eyre justice, then, will be to exchange temporal templates for timeless truth; thus will we employ Bronts own words, the established facts of her life, and a close reading of Jane Eyre to illuminate Janes ultimate witness to her obedient faith and reason. As we retrace Janes path, we will note that her deep, often overwhelming reactions to her environment reflect first her moral immaturity and then, before long, her moral growth. Increasing harmony with her surroundings evolves as Jane moves from Gateshead, where she is completely unguided; to Lowood, where her moral mentor initiates Janes religious sensibilities; to Thornfield, where she must morally confront her temptations and frustrations; to Marsh End and then Ferndean, where she will find communion of her faith and her desires. At the novels conclusion, she achieves emotional moderation and thus internal happiness.

To be sure, Janes pensive nature, her lack of familial support, and her innocent ignorance of the truth of forgiveness and salvation form the framework for the Gateshead section of the novel. Confronted at once with clouds so sombre, and

Although Charlotte lost her mother to illness when she was a mere five years old, still, her early years surely were more positive than Janes, for she had the freedom to enjoy her fathers extensive library and the love of siblings who shared her interests and sensibilities. While for the Reeds Jane is a useless thing, incapable of serving their interest (see ), Charlotte had true companions in her sisters and brother. These contrasts notwithstanding, however, there are surely parallels to be drawn between the lives of young Jane Eyre and her creator. The death of Janes uncle Reed is the catalyst for the novels action and movement, just as the death of Mrs. Bront when Charlotte was five changed forever the lives of the Bront children. At that point, they became, in a certain sense, orphans like Jane.

Charlotte was not a singled out victim of her home, as is Jane, but the overt lack of parental affection and support is common to them both. Gateshead itself is clearly grander than the Parsonage at Haworth, as are the means of the Reed family compared to the Bronts, yet Jane, like Charlotte, suffers isolation from the outside world. Having moved to a place as remote as Haworth for Reverend Bronts career, the Bront sisters grew up out of childhood into girlhood bereft, in a singular manner, of all such society as would have been natural to their age, and, like Jane Eyre, Charlotte was often found lost in a book. Interesting, though, is the striking difference in their religious formation. In the red-room, Janestill relying solely on instinctinnocently and ignorantly fears Gods pity and briefly considers starving herself, while Charlotte was well-versed in Christianity, owing to her fathers vocation and, perhaps even more, to the model of her elder sister Maria. In Charlottes novel, the great lack of moral influence in the Reed household serves to propel Jane to her next location, a location in which her model and mentor is found and without which the Jane we know could not exist.

Indeed, as we witness the fictionalized Maria in the character of Helen Burns, we will note also, as we do in the Gateshead section, the voice of mature, retrospective Jane in contrast to the younger, sometimes irrational Jane. It will be as Jane moves physically among locations and mentally between emotions and beliefs that the irrationality will wane to allow for her waxing maturity and faith. At this early stage, though, young Jane, so deprived of any true religious formation, is clearly in need of guidance. Of course, at only ten years old, she cannot conceive of the changes to come, but she decidedly chooses to leave, knowing it implie[s] a long journey, an entire separation from Gateshead, an entrance into a new life (see In Janes brief but so integral time with Helen, the lessons learned seem almost ethereal, until we witness their palpable fruition at the novels conclusion.

Next page