Acknowledgements

Deepest thanks to both Heather Wardell and Christian M. Lyons for beta-testing and error-checking this manuscript, in record time, no less. You did wonderful jobs, and made terrific suggestions, and this book is much better for your comments.

The remaining errors, of course, are all mine.

Holly Lisle's Create A Culture Clinic

SECTION ONE Why and How

Why Create Cultures?

Or "I Write Mainstream, So I'm Off the Hook ...

Right?"

No writer is ever off the hook where culture is concerned, because every story ever written is, was, or eventually will be about cultures.

Really.

There was a science fiction story once in which a man was able to disguise the fact that he was alien by wearing a hat on his head to cover his antennae. All men wore hats almost all the time, so he didn't stand out. The writer assumed that hats were essential to men, and that men would always wear them. And then the culture changed, hats went away, and the story now seems broken.

Novels set in the time of the writer frequently assume culture, and hope the reader will share (or at least comprehend) the culture the writer is assuming. These novels are written for the day and the moment; they'll be unreadable in twenty years. If you want to write for the ages, your writing has to have complete, working subsets of all the cultures you wrote about IN the novel. Every single time. Cultures change. Dickens and Twain are still comprehensible today because they included right in their stories everything you needed to know about how their worlds worked. Their contemporaries are gone because they assumed that their readers would live in a world just like the one they lived in, and would simply understand all the things they left out.

Deeper novels draw out the cultures as richly as they draw out the characters. Novels set in the present show the present and those cultures working in it, and through the lives and actions of the characters demonstrate how their cultures work for and against them, and how the characters work for and against their cultures.

Novels set in the historical past show how cultures and life paths most of us have forgotten create unique problems and shape the people who inhabit those worlds to deal with those problems. Novels set in the future must extrapolate multiple cultures that contain features our world might someday have, while those novels set in worlds than never can be play with cultures that contain features no culture in our would can ever have.

From romance novels to Christian fiction to chick lit to Stephen King and Dean Koontz, to coming of age and coming of middle age and other literary novels, to Harry Potter and American Psycho, you as the reader are immersed in the details of lives lived within a set of cultural expectations, or lived outside of those same expectations.

When the writing works, we get magnificent fiction that tempts us to look twice at our own lives, to question our own assumptions, to get more out of our existence than we did before. And the writing works when writers understand the cultures about which they're writing, and are able to look at them and identify the cultural assumptions that exist, and then are able to use those assumptions to shape their characters and their storytelling.

When the writing doesn't work....well, you get one million 1970's Harlequin Romances in which a nineteen-year-old virgin fell in love with a thirtysomething power-addled jerk, and was thrilled to be talked down to, dragged around against her will, and taken by force, because she knew that love would change him.

You also get Westerns set in Too Much, Texas, and SF flowering in the belly of a generation ship and fantasy galloping through Elfhame and historical romances primping in Regency England, and suspense novels skulking through the dark heart of Paris...in which the cool settings are nothing more than painted paper backdrops, because the characters all came from yesterday's Wal-Mart, complete with vocabularies, attitudes, and expectations.

You get stories in which characters do incomprehensible things for no discernable reason.

You get novels in which people end up nearly wrecking their lives over a misunderstanding that two four-year-olds could have solved over the phone, because the writer couldn't see the possibilities for real conflict inherent in his world.

You get crap, in other words.

You don't need to get crap. You don't need to read it; far more importantly, you don't need to write it. Creating and comprehending the workings of living, breathing cultures, whether real or fictitious, will give you enough deep, powerful conflict for a lifetime of writing; will permit your characters to act in ways that are surprising and sometimes shocking, but that make sense for them; will give you more good, strong, compelling story ideas than you know what to do with; and will make your stories, no matter when and where they're set, feel real.

Better yet, creating cultures is an entirely doable process. It isn't always straightforward. Once in a while it will drive you batty. Occasionally it may require more of you than you really wanted to give. Mostly, though, it's incredibly fun, and fascinating, and more often than not you'll have to stop before you want to, simply because...well, you do have to write sometime.

And the end results for your fiction, no matter what sort of fiction you write, will be worth it.

How To Use This Book

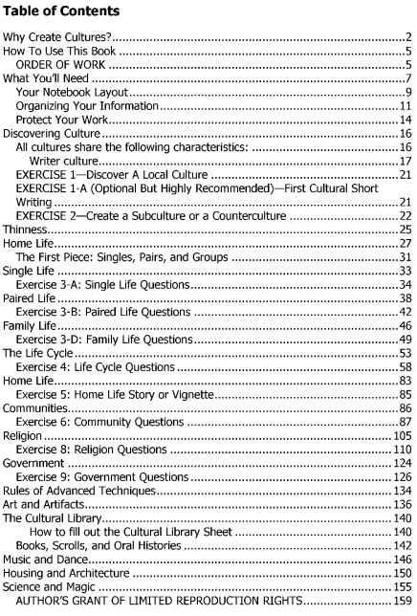

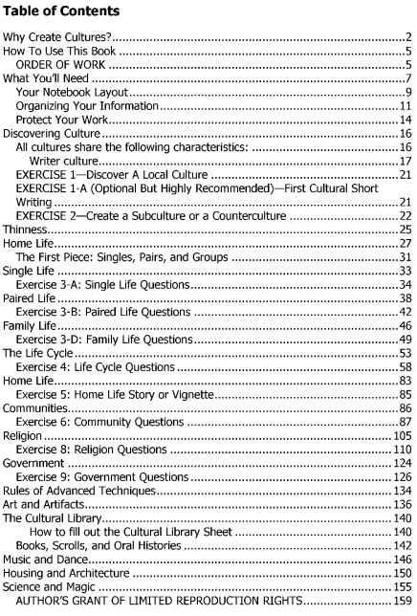

SECTION ONE: How and Why is devoted to general set-up-making sure you know how to use the book and have the supplies on hand when you sit down to work on your culture in order to make the experience as fun and stress-free as possible.

SECTION TWO: Basic Culture Building is further divided into the following categories: Personal, Community, Religion, and Government, and contains discussion, examples, and exercises designed to help you develop the heart of your culture while avoiding common mistakes.

SECTION THREE: Advanced Techniques For each question you answer, you can choose to explore deeper using the advanced techniques. These techniques include creating non-existent books, religious rituals, songs, artifacts, and other tangibles that exist in the world you're creating, adding necessary detail to your culture.

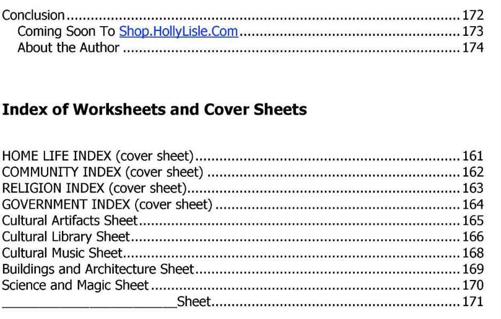

SECTION FOUR: Worksheets holds a stack of organizing tools to help you keep track of the work you've done, where you filed it, and what it contains. Most, though not all, of the worksheets are indexing tools.

ORDER OF WORK

Read all of Section One.

Put together your starter Culture notebook, or add a Culture section to the back of your Language notebook for the same culture.

Read or skim Sections Two and Three, using bookmarks or Post-it notes to mark a few questions that interest you and/or directly relate to the story you want to tell.

Go to the first Basic Culture-Building question you marked, and modify it, if necessary, to fit your world. (If you're working with aliens, different genders than male and female, sentient animals, or any other variants on the assumed basic human characters, change the terms to fit your needs.