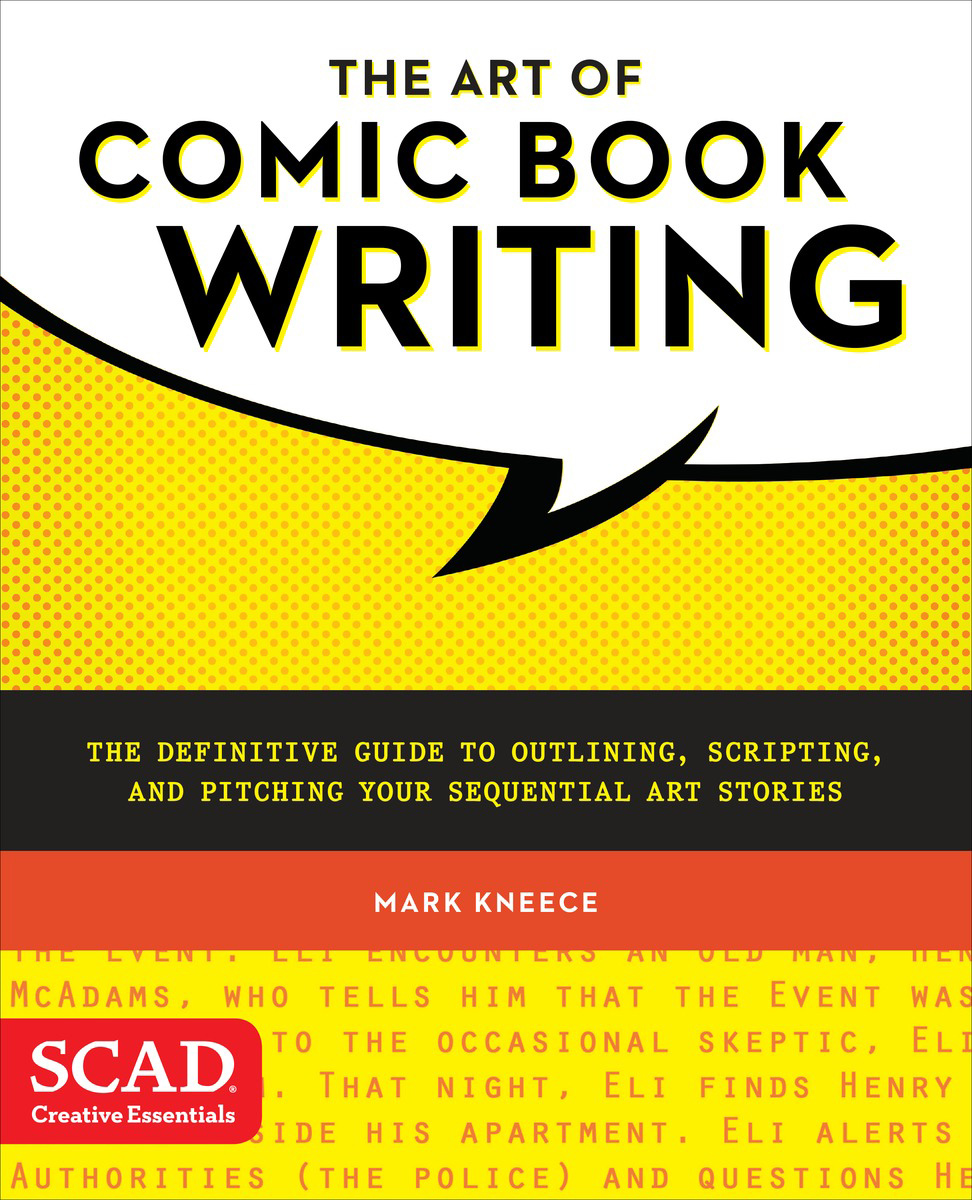

The SCAD Creative Essentials Series

The SCAD Creative Essentials series is a collaboration between Watson-Guptill Publications and the Savannah College of Art and Design (SCAD) developed to deliver definitive instruction in art and design from the universitys expert faculty and staff to aspiring artists and creative professionals.

Copyright 2015 by SCAD / Savannah College of Art and Design / Design Press

All rights reserved.

Published in the United States by Watson-Guptill Publications, an imprint of the Crown Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House LLC, New York.

www.crownpublishing.com

www.watsonguptill.com

WATSON-GUPTILL and the WG and Horse designs are registered trademarks of Penguin Random House LLC

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Kneece, Mark.

The art of comic book writing : the definitive guide to outlining, scripting, and pitching your sequential art stories / Mark Kneece. First Edition.

pages cm. (The SCAD Creative Essentials Series)

Includes bibliographical references and index.

1. Comic books, strips, etcAuthorship. I. Title.

PN6710.K63 2015

741.51dc23

2015007716

Trade Paperback ISBN: 9780770436971

eBook ISBN: 9781607747512

Design by Chloe Rawlins

v3.1

To my wife, Paula.

And to all the teachers Ive known, living or dead,

employed or unemployed, whove helped those

around them see things more clearly.

Comics writing is not only an art form, it is a difficult art form. The audience for comics writing is extremely narrow. The main audience is one person, the artist drawing the story. There may also be editors, publishers, colorists, letterers, or stalwart fans who are interested in what the original script looks like; however, most people never see it. Instead, they see the final product, the finished comic.

Story is the alpha and the omega of comics; it is that important. In comics, good art only goes so far if the story is lacking. On the other hand, we may sometimes forgive bad art if the story is interesting enough. The connection between narrative and art, however, is vital for creating comics stories. A comics writer must intimately understand how both aspects function, what works well, what doesnt work so well, and when to bend the rules a little. Not all comics writers draw, but no one can ever be a comics writer without a firm conception of what a story is and of how art can be manipulated to tell that story.

Story is an inescapable facet of comics art. If someone is interested in art only, but not the story, I would strongly suggest that that person put this book down right now and walk away. To that person Id say, go back to drawing and dont let me interrupt you any further. Dont get me wrong: Good art is important. I teach at a school where drawing is emphasized heavily. Students spend months mastering the figure, grappling with perspective, and wrestling with line weights, color palettes, T squares, and various complicated software programs in order to improve their art. Those skills are important; however, learning to manipulate text and art to create narrative is exponentially more difficult. It is not a given that everyone who knows how to draw will also know how to tell a story, much less how to write one. Sequential art serves one almighty masterthe story.

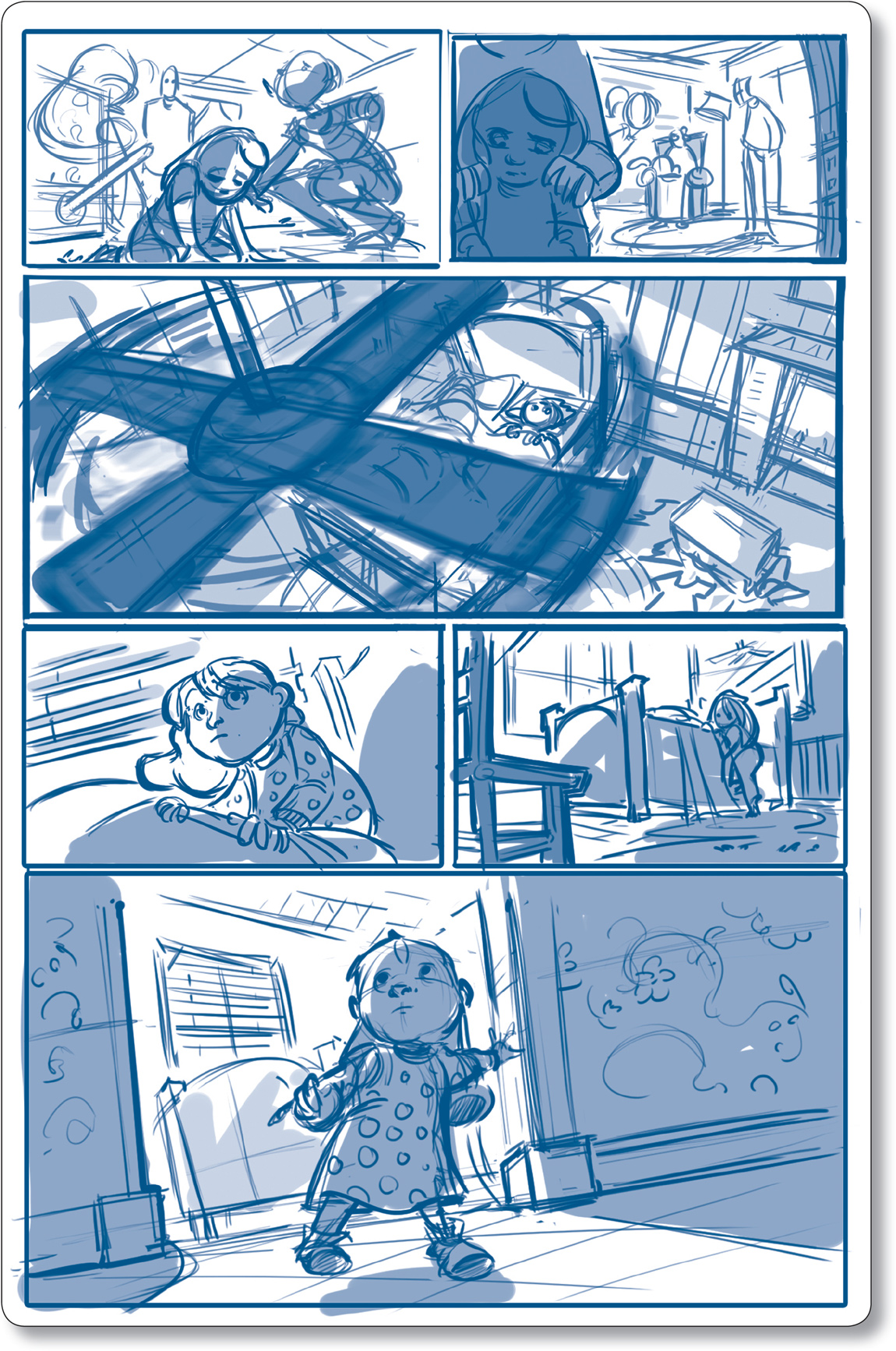

In comics, story is rigidly governed by the dictates of the page. The lack of movement and the use of panels generate all of the same problems for the creator of webcomics as for the creator of print comics. However, a talented comics writer crafts stories around the strengths of the medium. Static images in relatively small spaces can achieve power and drama.

The comics medium is more than just the stepchild of illustration and film. It has its own set of complex rules about what can and cant be done, about what does and doesnt work. No one really wants to read a comic book, at least not in the way one would read a prose novel, and no one wants to watch as if it were a movie. Thats the first mistake amateur comic book writers makeoverloading the script. They think about writing novels, films, or possibly even plays, instead of focusing on working in a visual medium where art rulesart that doesnt move, doesnt speak aloud, and doesnt occupy much space. Anyone who thinks that writing a comic is exactly like writing a film is dead wrong. Ask any screenwriter whos tried turning to comics writing.

Many comics writers turn to film-writing books as sources of information about storytelling within a visual medium. They are not bad places to go for some of the most basic principles. I personally use Robert McKees Story as a textbook in some of the comics writing classes that I teach. Somewhere along the line it occurred to me, wouldnt it be a good thing to have an in-depth book to cover the art of writing for comics ? When the opportunity arose, I decided to take the things that Id learned over the past two decades of teaching comics writing at SCAD and set them down here.

What makes this book so special, you might ask? Ive taught four classes per quarter, with ten to twenty students in a class on average, each and every year since 1993. In the last twenty-plus years, Ive taught somewhere in the neighborhood of four thousand students about comics writing. As a teacher, thats a lot of practice. Every new student is full of great ideas and has a lot of questions. The fun never gets old. Many of those individuals are out there somewhere right now, making me very proud to have helped them in some small way.