The breadth and range of work collected in Quagmire is a remarkable chronicling not only of war but of art.

Elliot Ackerman, author of Places and Names: On War, Revolution, and Returning

Quagmire is an invaluable anthology of the U.S. militarys experience of war in Iraq and Afghanistan. The voices are diverse: we hear not only from servicepeople but their loved ones, as well as journalists and Iraqi and Afghan civilians and soldiers, all delivering their immediate and often unvarnished accounts of loyalty, duty, valor, regret, guilt, and fear. But it is the quagmire of ambiguity and complexity that enlightens and compels the reader.... Many of these are stories that the tellers feel they should not or cannot share because the world will not listen. But the tellers break the taboo of trauma anywaythey make us listen with their generosity and artistryand in so doing they offer healing to us all.

Dan OBrien, author of War Reporter and The Body of an American

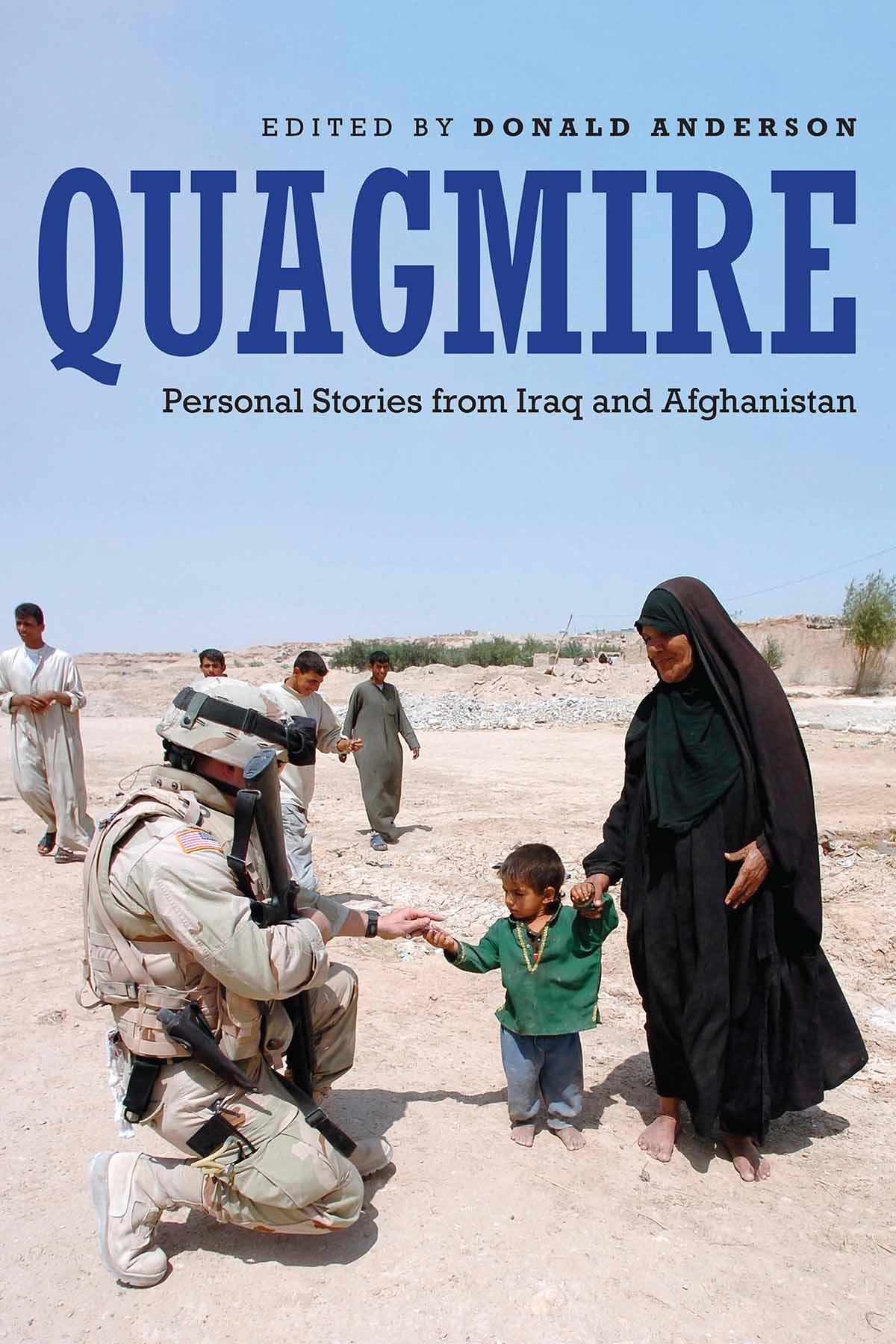

Quagmire

Personal Stories from Iraq and Afghanistan

Edited by Donald Anderson

Foreword by Philip Beidler

Potomac Books

An imprint of the University of Nebraska Press

2021 by Donald Anderson

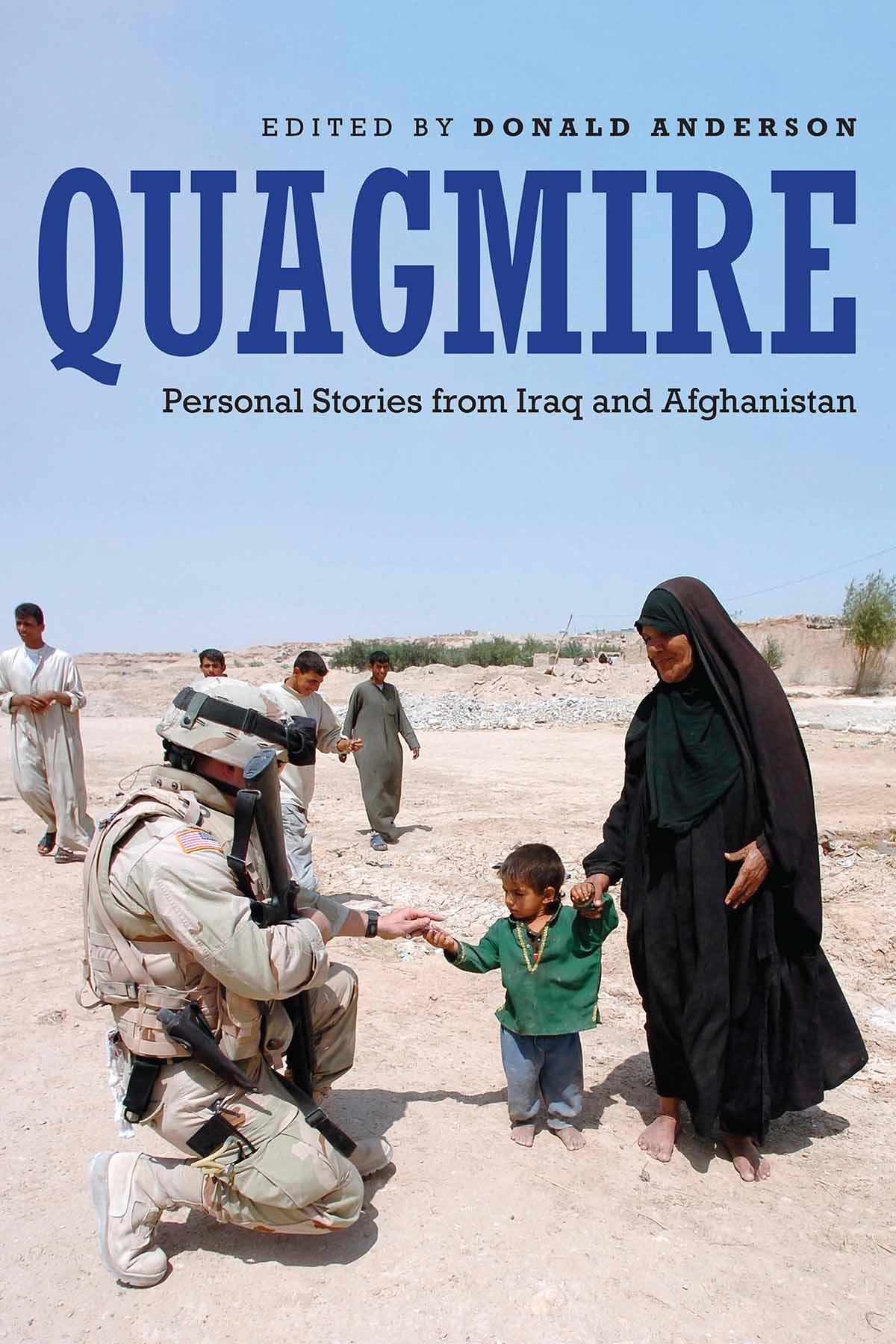

Cover designed by University of Nebraska Press; cover image Alamy Stock Photo/Stocktrek Images, Inc.

All rights reserved. Potomac Books is an imprint of the University of Nebraska Press.

The story Allawi originally appeared in Patrick Mondacas Adjustment Disorder: A Collection of Maladjusted Essays (Bauhan, 2021).

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Anderson, Donald, July 9, 1946, -editor.

Title: Quagmire: personal stories from Iraq and Afghanistan / edited by Donald Anderson.

Other titles: Personal stories from Iraq and Afghanistan

Description: [Lincoln, Nebraska]: Potomac Books, an imprint of the University of Nebraska Press, [2021] | Includes bibliographical references.

Identifiers: LCCN 2020057471

ISBN 9781640124523 (paperback)

ISBN 9781640124899 (epub)

ISBN 9781640124905 (pdf)

Subjects: LCSH : Iraq War, 20032011Personal narratives, American. | Afghan War, 2001Personal narratives, American. | BISAC : HISTORY / Military / Afghan War (2001) | HISTORY / Military / Iraq War (20032011)

Classification: LCC DS 79.766. A 1 Q 34 2021 | DDC 956.7044/34092273dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020057471

The publisher does not have any control over and does not assume any responsibility for author or third-party websites or their content.

Look west at the hill of water: it is half the

planet: this dome, this half-globe, this

bulging Eyeball of water, arched over to Asia,

Australia and white Antarctica: those are the

eyelids that never close; this is the staring

unsleeping Eye of the earth; and what it watches

is not our wars.

Robinson Jeffers, from The Eye

Contents

Donald Anderson

Jason Armagost

Rebecca Kanner

Patrick Mondaca

Nolan Peterson

Teri Carter

Jordan Hayes

Gerardo Mena

J. Malcolm Garcia

Bobby Briggs

Brian Duchaney

Alyssa Martino

Paul Van Dyke

Nicholas Mercurio

Matthew Komatsu

Thomas Simko

Raul Benjamin Moreno

Micah Fields

Jonathan Burgess

Jason Arment

Benjamin Busch

Brian Lance

John Whittier-Ferguson

Philip Beidler

A reader of this collection of personal narratives from the American wars in Iraq and Afghanistanpartaking also of the critical insights of Donald Andersons prologue and of John Whittier-Fergusons epiloguewill gain a new knowledge of what happened there; or, to be more precise, what horrific enterprises the Iraq and Afghanistan wars turned out to be over the years for a myriad of participants in a plethora of assignments, actions, duties, and locales. In this respect, one should begin by noting emphatically that the title, however ironically chosen, says exactly what it means: that a postVietnam War America, having extricated itself toward the end of the twentieth century from the morass of Indochina, at the beginning of the twenty-first actually found it possible to create a new military and geopolitical quagmire in the desert. I, for one, on the basis of reading these first-person narratives, feel that I actually may now at least begin to comprehend in very direct and concrete waysas I never did beforewhat an incomprehensible, ghastly mess the whole decades-long endeavor turned out to be. Indeed, I should go so far as to say, the collection as a wholestudded, as one might expect with all the bizarre new acronyms and nomenclatures comprising the nations latest glossary of warSandbox, Humvee, MRAP , IED , Hillybilly Armor, LN , TCN , TCP , MRE , Moondust, DFAC , Fobbit, T-man, Johnny Jihadat many points makes me think that my own war fifty years ago in Vietnam was by comparison reasonably coherent. Twenty-four hours a day, for weeks at a time, we went out to find the enemy and kill him. All the rear-area stuff and strategic confusion was just background noise to most of us. Yes, we heard about all kinds of strange, off-the-wall missions. The LRRP s, the Green Berets, the secret SOG Cambodia stuff, and the Phoenix assassination teams. And, to be sure, we had our own superabundant supplies and varieties of housecats: clerks and jerks, we called them, Remington raiders, REMF s (rear-echelon motherfuckers). All over the country we built back-in-the-world installations: barracks, mess halls, PX s, Officers and NCO and EM clubs packing plenty of beer and soda. By the end, MACV with all its allegedly advisory and assistance programhad its own Pentagon West campus outside Saigon.

In contrast to even this prolonged military train wreck, what I get out of the Quagmire narratives is that there never really was anything resembling a mission to begin with and that the longer we stayed in Iraq and Afghanistan the more bizarre and incoherent it all becameno matter how or where one was deployed. And that, I must say, is to me the most concentrated composite effect of the essays: that there were nearly as many wars going on as there were different participants in different situations over a nearly interminable period of years. And, if anything, the differences themselves were breathtaking, again even for a Vietnam War veteran who thought he had seen the most of it. Here a roadblock, erupting into the latest shooting up of a carful of civilians, seemed to be an everyday occurrence. With the flick of a cellphone an incredibly powerful IED could turn any patrol into a bloodbath. Anyone on the street truly could be a suicide bomber. (Hence the mantra, Be professional. Be polite. Be prepared to kill everybody you meet.) Weeks and months were spent on the most utterly exhausting missions of house-to-house fighting. Sometimes the city was Mosul or Kandahar. As often, a young American on his second or third tour would find himself assigned to the second or third retaking of Mosul or Kandahar.

The work included here is generally so powerful as to reduce one into appalled silence. We follow the globe-girdling flight of the B -2 bomber command pilot who initiates the war precisely on time by dropping its bomb directly down the shaft of Saddam Husseins fhrerbunker. A young Marine at a roadblock relents at the last moment from opening fire on the automobile of a confused, frightened civilian trying not to be late for work, but then ponders whether he will go home scorned as the only U.S. Marine who has never killed anybody. A former Chinook pilot at an elegant Sunday brunch with old college friends tells a gruesome war story with every intention of spoiling his complacent, privileged companions football weekend. Here then, ranging from the horrific to the banal, is a true literature of witness. Something changes radically in the lives of those who have looked upon the face of battle. To borrow from Donald Anderson, the phrasing the voice that knows says it all.