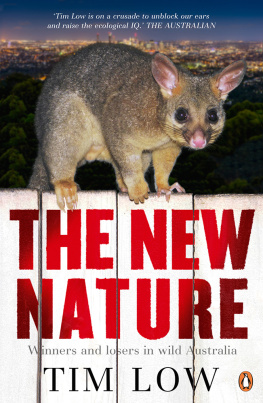

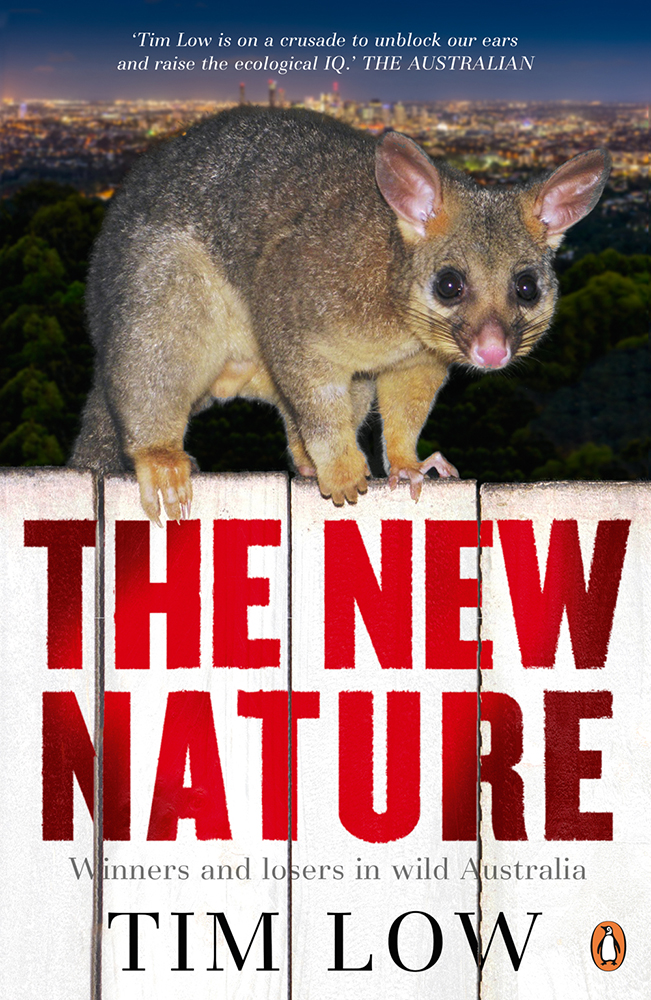

Nature isnt confined to the wilderness, it lives in out cities and gardens, exploiting everything we do, forging new connections with us. Endangered species are turning up in industrial zones. In our forests, certain native creatures have become pests and are now a force to be reckoned with. Sheep are being kept in some national parks to protect rare birds and plants. We need to know why.

In so explaining, Tim Lows groundbreaking book will change your view of nature. This edition has a new introduction that shows how important it is to understand the relationships we have with nature today.

Low argues with a novelists zeal that the line we draw between good, pure, harmonious nature and evil, selfish, destructive humans is as artificial as the blue plastic that bower birds seek out to decorate their forest boudoirs. TIME

A welcome dose of reality. THE AGE

[Tim Low] makes a strong case ... for the need for a new understanding of the natural world. And he does so in a popular style that is accessible to the non-scientist. SYDNEY MORNING HERALD

Beauty and purity are qualities we identify with nature, which encourage us to care for it. But if we are too sold on natures perfection, our thinking about other species will be unrealistic, leaving us blind to some serious environmental problems. These need our attention, which is why, more than a decade ago, I wrote this book. To some extent, the nature of the book ended up a surprise to me. I never expected to be celebrating sewage or criticising wildlife-friendly gardening.

We would do well at times to consider ourselves part of nature rather than always on the outside. This can be satisfying, and at the same time help us understand more of what we see. Native animals dont have any concept of unnatural, so they dont necessarily recoil from humanised landscapes. The native animals in our cities are not there, most of the time, as refugees from habitat loss, but because cities meet their needs. We shouldnt presume that nature, merely by definition, wants to be natural. The words nature, natural and wilderness can end up misleading us about the natural world. The environments we create are often rich in resources for those that can exploit them. It might seem heretical to say this, but cities and farms provide some species with better habitat than anything natural, which they show by living in high densities. Like humans, brushtail possums, rainbow lorikeets and bluetongue lizards reach their peak densities in cities.

One reason it is beneficial to focus on this is that many Australians are dismissive of any environmental crisis because they see parrots and other bold native birds thriving in cities around them. When the conservation message sounds too much like nature is suffering, it is easily shrugged off as exaggeration. To bring more Australians on board, the environment movement needs to talk more about winners to ensure that its messages about losers are considered credible.

Winners also matter because some of them are ecologically powerful. Instances keep emerging of thriving native animals doing harm to endangered species or habitats. The crown-of-thorns starfish plagues stripping bare the Great Barrier Reef are an infamous example, but there are many others, and more can be expected in future. We cannot care for the environment properly unless we acknowledge that native species, responding to us, represent one of the big conservation issues in Australia.

In the fifteen years since I wrote this book, climate change has become a central issue and an ideal test of what I wrote. If there are species that can profit from anything we do, we would expect to see climate change winners emerging as a new conservation concern. I had a chance to assess this when, as a result of this book, I was invited to join the federal environment ministers Biological Diversity Advisory Committee. In 2006 I ran a workshop in Canberra on climate change and invasive species, which included native animals, plants and diseases. Striking stories emerged.

In Tasmania the long-spined sea urchin (Centrostephanus rodgersi) is turning lushly productive sea beds into barrens with limited marine life by overgrazing the seaweeds. Along with various fishes, it was conveyed south from New South Wales by a warming of the East Australian Current. The Institute for Marine and Antarctic Studies rates it a very significant threat to Tasmanias shallow reef systems. Overfishing of rock lobsters, the main predators of urchins, is part of this problem.

In the Australian Alps, kookaburras reaching higher altitudes are preying on alpine lizards that fail to regard them as dangerous. The Australian Department of the Environment lists them as a problem for the endangered Guthega skink (Liopholis guthega). Swamp wallabies and red-necked wallabies also moving to higher altitudes threaten the future of alpine herbfields. Snow gums are not (yet) creeping upslope, but when they do they will displace alpine plants. Experiments around the world show that alpine shrubs and herbs can tolerate high temperatures, but they will lose out from trees that shade them out (and from drier soil). Many species on mountains have their lower altitudinal limits set, not by temperatures directly, but by other species that limit them wherever temperatures are high enough. The problems of climate change will very often come in the form of native species causing harm. The evidence for this is compelling: in Australia very few species have yet moved in response to warming but several are already problematic.

However, when climate change is talked about, the migration of species southwards and upslope is nearly always portrayed as desirable. Most of the time it will be, but the exceptions show how important it is to understand the problems native species can cause. In chapters 11 and 13, I mention the downsides of lyrebirds and mucor fungus establishing in Tasmania, as well as pandanus planthoppers in southern Queensland. Their spread south had little (if anything) to do with climate change but shows that species movement (in any direction and for any reason) can bring problems. As for humans deliberately moving species to help them survive climate change, I am pleased to say there is recognition in Australia that risk assessments should be conducted first.

I am reluctant to go straight to another bleak story, but I must mention one of the big surprises of the past decade the evidence that the sugar gliders taken to Tasmania in the 1830s (chapter 12) are proving a disaster for endangered swift parrots and orange-bellied parrots (chapter 23). A recent study with motion-triggered cameras showed that these cute little gliders overpowered and ate the female bird in twenty of the seventy monitored nests. Warning of imminent extinction for the parrots, researchers at the Australian National University launched a crowd-funding appeal to buy a thousand glider-proof nest boxes. Sugar gliders are well known animals, but before camera traps came into use they werent known to eat birds or their eggs. Had climate change justified moving sugar gliders south, anyone conducting a risk assessment a mere decade ago would not have predicted this outcome. It shows how very careful we must be about translocating species. I am not saying that species should never be moved, but that anyone contemplating this should be very well-informed about past problems. The glider situation turns out to be complicated, with camera traps revealing that sugar gliders and squirrel gliders are preying on endangered regent honeyeaters in Victoria as well.