For my mother, Pamela Jean Schneidau

and my grandmother, Florence Annie Stratton

with love

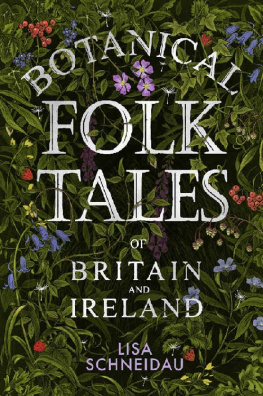

Cover illustrations: David Wyatt

First published 2018

The History Press

The Mill, Brimscombe Port

Stroud, Gloucestershire, GL5 2QG

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

Lisa Schneidau, 2018

The right of Lisa Schneidau to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without the permission in writing from the Publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 0 7509 8121 7

Typesetting and origination by The History Press

Printed and bound by CPI Group (UK) Ltd

eBook converted by Geethik Technologies

CONTENTS

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Lisa Schneidau trained as an ecologist. She has worked with wildlife charities all over Britain to restore nature in the landscape, in roles including farm advisor, river surveyor, political lobbyist and conservation director. Lisa is also a professional storyteller, sharing tales that inspire, provoke curiosity and build stronger connections between people and nature. She lives on Dartmoor.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Where possible, I have drawn on multiple sources for every traditional story retold in this book. My huge thanks to all the folklorists, botanists and authors whose work has influenced and informed the stories. I have provided a full list of references and sources, but Im particularly grateful to Katherine Briggs, Richard Mabey, Jacqueline Memory Paterson, Niall Mac Coitir, Ruth Tongue and Roy Vickery. Thank you to Halsway Manor Library and the Ruth Tongue Archive for allowing me to interpret some of the lesser-known folklore that Ruth collected. My thanks also go to all the storytellers who have collected and shared these tales in the telling, and upheld the oral storytelling tradition through the generations. I hope that I have honoured their stories well here, and added something useful to the tradition.

Thank you to the storytelling community they have been very generous in their support of this project and in pointing me towards story sources. Particular thanks to Michael Dacre, Nick Hennessey, Sharon Jacksties, Lisa Kenwright, Clive Pig, Jess Wilson, and to Shonaleigh Cumbers and Simon Heywood, who suggested I write this book in the first place. Many story audiences and school groups have listened and shared my stories during the last few years and given feedback and ideas, and they have helped to shape the content of this book.

Thank you to David Wyatt for his stunning cover artwork, and to everyone at The History Press for their support and advice in bringing the book together.

Im grateful to Ronnie Conboy, Moira Houghton, Karl Schneidau, Beccy Swaine and Jo Swift for proofreading and comments on the text. My father Oscar Schneidau, my brother Karl, and my family and friends have provided amazing support and encouragement throughout the project.

INTRODUCTION

I was lucky. I was a little girl growing up in 1970s Buckinghamshire with a mother and a grandmother who loved wild plants, and six fields of ridge-and-furrow, green-winged orchid meadow behind our house.

I remember when the moon daisies were nearly as tall as me, when we picked field mushrooms from the fairy rings and fried them for breakfast, when I could run through the middle of ancient hawthorn hedgerows and travel by the secret ways down to the magic old willow tree over the pond. I remember the carpets of cowslips, the endless blue butterflies, the quivering quaking grass, and the blackberries in autumn.

When we werent exploring the fields, we were out looking for orchids on Ivinghoe Beacon, plant-spotting along the canal towpath of the Grand Union Canal, picking sloes on Dorcas Lane, collecting conkers at Mentmore or kicking the prickly sweet chestnuts around at Woburn. I inherited an insatiable curiosity for plants of all kinds and, with a vivid imagination as always, I wanted to know the stories: why? what? how does it feel to be a green living plant, a meadowsweet compared to a bee orchid?

Some time around 1980, the local farmer attacked our beloved fields. In the space of a week, the hedgerows had been razed, the land drained and the grassland ploughed up. Our willow tree house was cut down. One single crop of carrots was grown in the heavy Thames clay and then the land was left for fallow. In a single act of mindless vandalism, following the farming policies of the time, our wildflower paradise was gone. I can still feel the knot of deep grief that twisted in our bellies that year. Wed never heard of nature conservation, which was still in its infancy at that time.

Two science degrees, many years of working for wildlife trusts all over Britain, and many conservation projects later, storytelling found me. I was intrigued by the tradition: the richness of the stories, the skill and generosity of the tellers. Here were ancient tales that had been good enough to be passed down the generations, that might hold some of the old ways and the old wisdom. Storytelling caught my imagination and I started to try it myself.

I watched the storytellers at nature reserve events. They were telling stories of Coyote from America and Anansi from Africa. They were great stories, but they came from thousands of miles away; they had little to do with the nature and landscape that we were in. Where were the stories of this landscape, the things that grow and live and die here, the traditions of our own wildlife? And could those stories help us, living in Britain and Ireland, to reconnect to our own fragmented ecology?

This book is the first result of my search to answer those questions.

Here are thirty-nine folk tales about plants from Britain and Ireland. I have chosen this geography because plants dont respect political borders, and because of the ways in which the cultures of our countries share a common heritage. Although there is a wealth of plant folklore in these islands, actual folk tales with plants as a main feature are more occasional. They include stories about wildflowers, trees, and plants used for food, fibres and other human uses. I have chosen the stories that I particularly like and that I feel resonate with our natural history and our heritage.

These are my own versions of traditional tales. I have hunted out stories from many different sources: folklore archives and collections, natural history literature, and of course listening to storytellers. Some tales are well known, others more obscure. Like all storytellers, I am grateful to those who have collected and told these stories all down the generations, known and unknown. I have tried wherever possible to pursue a story back to its oldest referenced source. A list of story sources and further reading is provided.

The stories are presented according to the wheel of the year, starting when the sun is at its lowest at the winter solstice and continuing through the seasons and the old festivals. This is a very natural way to work with our stories about plants, even better if they are being told outside in the wild. Often the stories contain magical beings such as fairies, giants and pixies. I will leave it up to you to decide how much these characters represent the interface between humans and nature the magic of life where nature cannot speak for itself and how much they might be real!

Next page