EDITORS

SARAH A. CORBET, S C D

P ROF . RICHARD WEST, S C D, FRS, FGS

DAVID STREETER, MBE, FIB IOL

JIM FLEGG, OBE, FIH ORT

P ROF . JONATHAN SILVERTOWN

*

The aim of this series is to interest the general

reader in the wildlife of Britain by recapturing

the enquiring spirit of the old naturalists.

The editors believe that the natural pride of

the British public in the native flora and fauna,

to which must be added concern for their

conservation, is best fostered by maintaining

a high standard of accuracy combined with

clarity of exposition in presenting the results

of modern scientific research.

Contents

A HUNDRED YEARS AGO Arthur Tansley edited a book entitled Types of British Vegetation, written by the botanists of the Central Committee for the Survey and Study of British Vegetation. This book of 1911 was the first account of its kind, written for the benefit of a small and select international group of botanists invited for a countrywide excursion, and describing associations of plants that define our vegetation. He wrote a greatly enlarged account of the vegetation of Britain and Ireland in 1939, a landmark in the study of our vegetation. It was made possible by the strong tradition of the study and recording of our flora, which goes back long before this synthesis, maintained by a multitude of field botanists, very often county-based. It is their local knowledge that has been essential for understanding our vegetation and its composition. Since Tansleys time, the vegetation of Britain and Ireland has been studied in much more depth, with results often presented in the many New Naturalist books written about the natural history of the regions or more generally about plants or particular groups of plants, such as the early volume on Wild Flowers (1954), which ran to many editions. The present book is indeed timely in the sense that so much has been learned in recent years about our changing flora and its distribution, stimulated by the mapping projects of the Botanical Society of the British Isles and county botanical recorders. The more recent recognition of the significance of biodiversity has also promoted our interest in the flora and its distribution, especially in respect of the importance of the nature of environments in determining distribution, perhaps less well-understood and understudied in earlier years. The wealth of information now gained needs to be seen against the wider background of the plant communities that form our vegetation. Such needs have resulted in classification of our vegetation in more formal ways, remembering that any ordering presents just a necessary snapshot in a changing world. Michael Proctor has an unrivalled and practical life-time knowledge of our flora and vegetation, with expertise about both higher and lower plants, also reflected in his earlier New Naturalist book with his colleague Peter Yeo on The Pollination of Flowers (1973). He is also a very experienced photographer his photography appeared in the original New Naturalist Wild Flowers as will be seen in the illustrations. The treatment of the major classes of vegetation, following discussion of the essential historical aspects of the subject, places local floras in the wider context of the vegetation of Britain and Ireland, an original aim of Tansley, now realised so well by Michael Proctor.

T HIS IS PRIMARILY A BOOK about the common plants that give the colours to our countryside. What makes some plants common is as interesting as what makes others rare. The most interesting plants of all are often those that are neither very common nor very rare, but are characteristic of particular soils or particular situations in the landscape. They prompt that classic New Naturalist question, why?

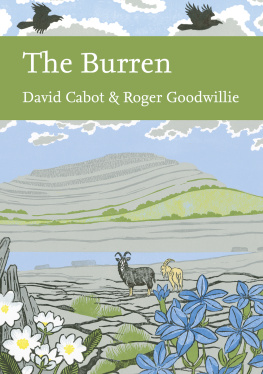

I have always been fascinated by vegetation, and by the subtle, and sometimes striking, colours with which it paints our landscape. My mother had a cherished copy of Bevis & Jefferys 1911 book British Plants: their Biology and Ecology from her schooldays, which I read avidly, and soaked up the findings of early British plant ecology. Oakbirch heath was recognisable on Harrow Weald Common within easy reach of our home in Harrow, and I knew (or could visualise) many of the other vegetation types described. The Chilterns lay to the north of us, and my aunt lived in Woking close to Surrey heathland, which was much more extensive then than now. In 1946 we moved to Hampshire, so in my mid-teens I found myself within easy cycling distance of the New Forest on one side and Purbeck on the other. Undergraduate years in Cambridge brought me into contact with inspirational teachers (of whom I owe a particular debt to Harry Godwin and Max Walters) and fellow students, and gave me a new landscape to explore. Subsequent postgraduate work provided the incentive and opportunity to get to know better the British chalk and limestone, and to make the acquaintance of Scotland, Connemara and the Burren. A first job in the Nature Conservancy in Bangor, and hill walking in Snowdonia in every month of the year, brought home the varied colours of the hill grasslands, at their best and most distinctive in autumn. In the high summer months they all too often merged into a near-uniform green, a dead loss for landscape (and ecological) photography!

The present book has had a long gestation. In 1968, I revised the late Sir Arthur Tansleys Britains Green Mantle for a second edition. About 1975, Allen & Unwin, the publishers, wrote to me asking whether I would consider revising it again for a third edition. I demurred, for two reasons. First, so much new material was appearing that I feared that so much new wine would burst an excellent old bottle. Second, in 1975, we were just embarking on fieldwork for a National Vegetation Classification (NVC) and it seemed inappropriate to embark on a new popular book until the NVC was finished. In the event the first of the five volumes of British Plant Communities appeared in 1991, and the last in 2000, rounding off a no-less-astonishing achievement on the part of John Rodwell, who saw the project through and wrote almost all the text, than Tansleys British Islands and their Vegetation half a century earlier. All thought of a new semi-popular book on British and Irish vegetation had been put on hold during the NVC project. When the New Naturalist on the Natural History of Pollination, which I had written jointly with Peter Yeo and Andrew Lack, was published in 1996, Collins asked me if I had another New Naturalist I would like to write. Fifteen years have passed since then, largely because I had greatly underestimated how long it would take to work up accumulated research data (some of which finds its place here) on chemical analysis of mire waters, and bryophyte physiology. A positive spin-off of the delay is that, with a new millennium, it is easier to put the long shadow of Tansley behind us, and take a fresh look at British and Irish vegetation in the light of twenty-first-century realities.

This book is intended to be readable, informative and sometimes thought-provoking. It is in no way a textbook. It is aimed at anyone interested in natural history or in our countryside. I am aware of writing for two constituencies, those who habitually use Latin names of plants, and those who are happier with names in the vernacular. In my experience few people are fully bilingual in this matter! Continental readers (of whom I hope there will be many) are likely to find Latin names more accessible than English names. Both Latin and English names of vascular plants follow the second edition of Clive Staces