Contents

Guide

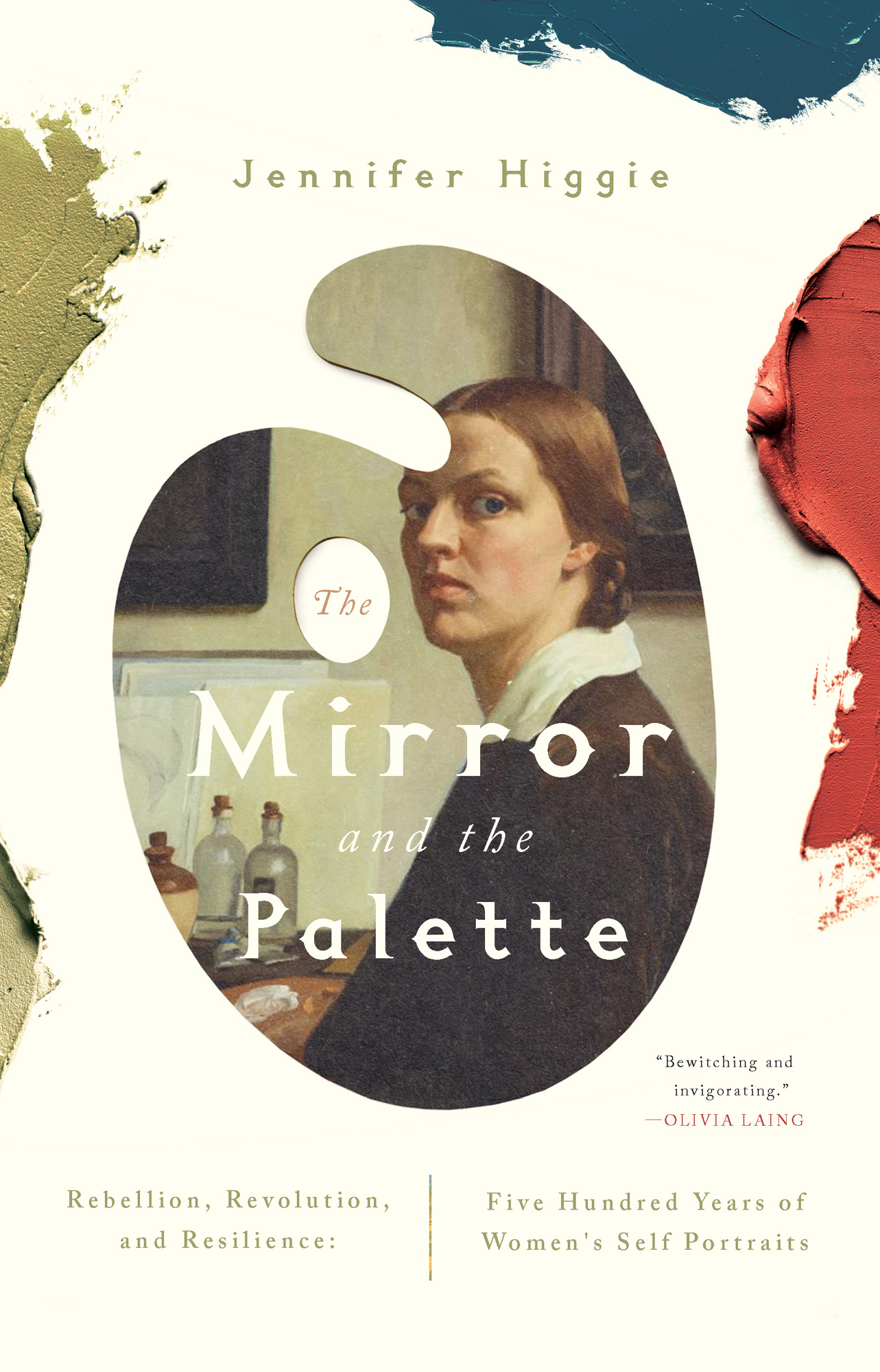

Jennifer Higgie

The Mirror and the Palette

Bewitching and invigorating.

Olivia Laing

Rebellion, Revolution, and Resilience: Five Hundred Years of Womens Self Portraits

To my mother, Jean Higgie

Prologue

Anyone who wanted could cite plentiful examples of exceptional women in the world today: its simply a matter of looking for them.

Christine de Pizan, The Book of the City of Ladies, 1405

She looks at herself, again and again. Shes in London or Paris or Helsinki or Sydney. Shes in a village by the sea or a hamlet in the mountains, in a room, a studio, a flat, a place, however small, she can call her own. Shes a mother, shes childless, shes straight, shes queer, in a relationship or relationships, happily celibate or filled with a longing for something or someone just out of reach. Shes finally found some time alone, perhaps even a moment of peace, even though theres a clamour in the streets: modernity is hurtling towards her.

Shes in competition with history, which has always been dismissive of her power. Until very recently, museums wouldnt buy her work, art historians wouldnt acknowledge her and commercial galleries would only rarely represent her. Shes a miracle, a marvel, a mystic, a seductress, a changeling, a visionary, a man-hater, a freak; shes never considered normal. She knows that no two women are the same. She knows that she has always been here, there and everywhere, but for reasons that baffle her, people still refuse to see her. Even now, decades or centuries after she has died, her magnificent achievements remain largely unsung; there are still countless museums, galleries and collectors who do not appreciate her worth, who do not rate her, who are not interested in the many stories she has to tell. She still has so far to travel.

For centuries, she couldnt enter the academy, even though she and her sisters never stopped pounding on its doors; nor was she allowed to paint anyone naked, not even herself. She couldnt vote and had little or no governance of her own body. She was all too often defined by the men in her life even if they meant nothing to her. She constantly struggled to support herself financially. She was mocked, excluded, ignored. She was laughed at, told what to wear, what to think, how to move through the world. Her appearance was always commented upon. If she was beautiful, her morals, her intellectual depth, her innate skills, all were questioned; if, according to the conventions of the day, she was considered plain, she was pitied and patronised. If she didnt conform, she was assumed to be mad. If she didnt have children, she was frustrated, frigid, grief-stricken, cold. If she did bear children, more often than not she disappeared for a while or forever; it was a rare husband who understood her need to paint. If she juggled art and motherhood, she was super-human. Time and again she had to work early in the morning or late in the evening, as during the day she had to run a household or earn money. She worked so hard its a wonder she didnt fall asleep on her feet. She scrutinised herself over and over again.

From the moment she was born, she was told who to be.

She paints a self-portrait because, as a subject, she is always available. (This is putting it mildly.) Shes been barred from so many other places, so many other bodies. Sometimes, shes unclear about why and who shes painting her picture for. (Does anyone really know what a painting is for?) All she knows is that something compels her to look at herself for hours on end, for reasons that have nothing to do with vanity quite the opposite. What draws her back to her reflection again and again is the raw self-scrutiny that stems from unknowing; from the confusion shes experienced between the reality of living in her body and the lies that shes been told about it that have been drummed into her since the moment she arrived on earth. She looks at herself in order to study what shes made of, to understand herself anew and, from time to time, to rage against the very thing that confines and defines her. She paints herself to develop her skills, to converse with her contemporaries and with art history. In the act of painting herself she makes clear that she is someone worth looking at, someone worth acknowledging. Her paintings assume shapes that she does not always predict. Against all odds, she discovers what she is capable of.

The Deceits of the Past

When youre an artist, youre searching for freedom. You never find it because there aint any freedom. But at least you search for it. In fact, art should be, could be called the search.

Alice Neel

The museums of the world are filled with paintings of women by men. Ask around and youll find that most people struggle to name even one female artist from before the twentieth century. Yet women have always made art, even though, over the centuries, every discouragement was and, in many ways, still is placed in their way.

In the words of the nineteenth-century writer and art critic Vernon Lee: There is no end to the deceits of the past. The story told by traditional art history is that, despite the occasional complication, creativity is a relatively straightforward and progressive affair. According to this tale, since the first cave paintings, one artistic movement has segued neatly into the next and each new artist has in some ways improved upon the one who came before him. Yes, him. Western art history began in sixteenth-century Italy, when the individuals who made paintings and sculptures became famous as artists, not just as craftsmen. It continued to prosper in the following centuries thanks, generally speaking, to the scholarship of privileged white men men who, despite their often original insights and scholarship, were blinkered: they tended, with few exceptions, to write about the achievements of other white men. Until very recently, the idea that women have always made art was rarely cited as a possibility. Yet they have and of course continue to do so often against tremendous odds and restrictions, from laws to religion and convention, the pressures of family and public disapproval. Apart from the occasional mention of these trailblazers by male historians, it is thanks to feminist art historians such as Rene Ater, Frances Borzello, Janine Burke, Whitney Chadwick, Sheila ffolliott, Frima Fox Hofrichter, Mary Garrard, Germaine Greer, Kellie Jones, Geeta Kapur, Lucy R. Lippard, Linda Nochlin, Rozsika Parker, Griselda Pollock, Arlene Raven, Gayatri Sinha, Eleanor Tufts and others that the achievements of these artists have at last been given their due.

Feminism has shaken up how art history has been read and written. For the first time, artists who were previously ignored, patronised, marginalised or ostracised due to their gender, race, sexuality or class, are being recognised for their originality and resilience. The infinitely varied work of these artists embodies the fact that there is more than one way to understand our planet, more than one way to live in it and more than one way to make art about it. This new art history celebrates and champions difference the very lifeblood of art. When I began researching self-portraits, despite being all too aware of the reality of gender exclusion, I was staggered at the sheer depth and variety of paintings made by women over the past five centuries who, it is fair to say, have, until recently, been erased from the story of art. The fact of their existence makes very clear that a segregation of the history of creativity or anything else, for that matter no longer makes any sense.