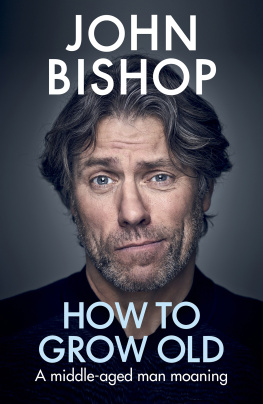

John Bishop

HOW TO GROW OLD

A Middle-Aged Man Moaning

CONTENTS

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

John Bishop was born in Liverpool and grew up in Winsford and Runcorn, Cheshire. He started his career in stand-up after a chance performance at an open-mic night when he was 35. Shortly before his 40th birthday he decided to quit his job to pursue a career in comedy; within three years he was playing to sell-out arenas nationwide and had released the fastest-selling debut DVD in history. In 2013 he wrote the Sunday Times bestselling, How Did All This Happen. John has been married to Melanie since May 1993, with whom he has three sons, and wherever he lives John will still always support Liverpool FC.

I would like to dedicate this to the older people in my life, who are important to me every day.

Ernie and Kathleen Bishop, my mum and dad. I would not exist without them and I would not be a fraction of the man I am had they not been my parents. I love them more than I can ever say. Mike Cornall, Melanies father, whose sharp mind and quick wit I have always appreciated. I learn from him every time we speak. Eileen Garnett, Melanies mother, who we lost as I was starting this book. Not many people have a mother-in-law as a friend. I did. We miss her dearly. She would have loved this.

INTRODUCTION

WHEN I DEVELOP A new stand-up tour, I tend to start from nothing. Some comedians carry a notebook around ready to pounce on anything that happens or is said, and which may be developed into a bit a bit being the universal comedians name for a piece of stand-up material. I have never operated like that, primarily because I came to comedy late and was too busy working and bringing up kids to be thinking what part of my life I could use on stage. I would go on stage, see what bits sprang to mind, and expand those themes further in subsequent gigs.

This is fine when you are doing ten-minute spots in comedy clubs. But when it comes to putting together a tour that needs two hours of new material, I often wish I had the discipline of noting down any bits that have happened. Essentially, I am not a joke-teller. When I am on stage, I talk about what has happened in my world: my life, therefore, is spent walking around, hoping that something funny happens. When something humorous does occur, I retell it on stage to a room full of strangers as long as I can remember it, of course. As I have now reached the stage in my life where I cant always remember what I did yesterday, that isnt guaranteed.

Having no notebooks to start from, I basically do tons of smaller warm-up shows, where I always seem to find the main things that are playing on my mind at that point in my life. Its a bit like therapy, as it helps organise my mind, if therapy consisted of standing in front of a room of unqualified people who I have asked to pay to attend. The process starts with standard room-above-a-pub gigs, moves onto small art centres with a few hundred people, and steadily grows in venue size as I develop the material into a full show.

I like this process more than if I prepared or you could say, if I acted more professionally! I know its counter-intuitive, but the less preparation I have for those early warm-up gigs, the better the overall end result is when I develop the full show. In the absence of any prepared material to fall back on, I find I am forced to allow the adrenaline to kick in and stimulate the creative process. Nothing activates your brain more than standing in front of a room full of strangers looking at you with expectant faces, waiting for you to be funny while all you have to offer is a blank mind and a microphone. I seem to find the material quicker in those situations than I do sat at home looking at the wall with a blank page and a pen.

This approach also means the material is more of the moment. It is based on the stuff that is currently happening or currently in my head, which makes it feel fresh and relevant. On my last tour, Winging It, two main things kept informing the material. Firstly, I had just turned fifty, and secondly, my kids had left home (by choice, I might add: we didnt just kick them out so I would have some material for the show, although I would probably have felt it was a price worth paying in the absence of any other bits).

When this books publisher, Andrew, watched the DVD of the show, he reported back that it was basically a middle-aged man moaning. However, this was much more of a positive than a negative, as he said there was a market for this as a book: many people were probably feeling the same, and Andrew suggested this could be used as a reference point for anyone in a similar position or about to face the same challenges. It was his suggestion to call this book How to Grow Old. It was my later suggestion to add the subtitle, A Middle-Aged Man Moaning.

I am now sat at home, tapping away at this introduction with the three-finger style I have developed as I never thought typing was going to be a skill I would ever require. I am part of the generation of men born in a time when only secretaries, journalists and authors knew how to type. Email, the creation of which has revolutionised communication, was not even invented when I entered the adult world of work, aged sixteen.

My first full-time job was as a mail lad (there were no mail girls, or mail persons of gender neutrality, in 1982) and my role entailed cycling around the ICI Rocksavage chemical plant in Runcorn, taking handwritten notes between the offices and plant rooms. The company sent its products all over the world and was regarded as the cutting-edge of technology, but could only operate because sixteen-year-old mail lads on bikes carried notes in brown envelopes between all the people involved in the production process.

ICI was regarded as a great employer, and often the old men I would see walking around the yard in company overalls and hard hats would tell me to stick with the company because I would get my pension, provided I progressed from the mail room and learned one of the skills the company required, such as operating some of the plant machinery. Nobody ever said to me, Listen, son, learn to type! Its the future and will change your life. It will save you from looking like a man with arthritis who can only use three fingers, when youre fifty-two.

Nobody ever said that because the office environment in those days really was paper shuffling. Today, I would imagine that the offices in ICI are filled with people on laptops typing away and communicating with the world instantly through their fingertips. Back in 1982, the phones had rotary dials on the front which meant even dialling a call would take five minutes. All written communication was on memo pads that had a space for the next person to respond to what was written in the box above, and to stimulate the next person in line to engage. What would now be done with a single group email would take days, as notes were carried from one part of the plant to another.

Part of me misses those times, because the frenetic speed we operate and communicate at nowadays doesnt seem to have served us very well. Everyone is stressed and overloaded with information, and email means that you are never really away from work. It is too easy to be on a family holiday and let the I just have to deal with this one email mentality creep in. Even if it is only thirty minutes away from the family holiday, it is still time lost you will never get back.

Next page