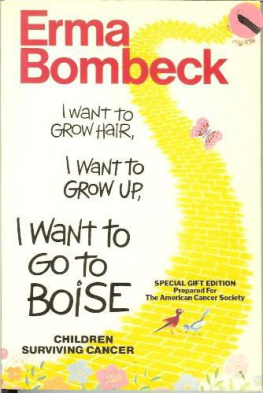

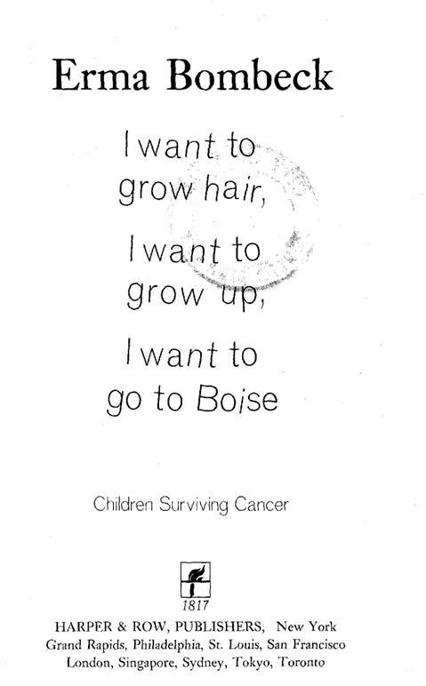

Bombeck - I want to grow hair, I want to grow up, I want to go to Boise : children surviving cancer

Here you can read online Bombeck - I want to grow hair, I want to grow up, I want to go to Boise : children surviving cancer full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. City: New York, year: 1990, publisher: Harper & Row;HarperPaperbacks, genre: Home and family. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:I want to grow hair, I want to grow up, I want to go to Boise : children surviving cancer

- Author:

- Publisher:Harper & Row;HarperPaperbacks

- Genre:

- Year:1990

- City:New York

- Rating:4 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

I want to grow hair, I want to grow up, I want to go to Boise : children surviving cancer: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "I want to grow hair, I want to grow up, I want to go to Boise : children surviving cancer" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Tells story about kids surviving cancer, sparkling with innocence and glistening with hope.

Bombeck: author's other books

Who wrote I want to grow hair, I want to grow up, I want to go to Boise : children surviving cancer? Find out the surname, the name of the author of the book and a list of all author's works by series.

I want to grow hair, I want to grow up, I want to go to Boise : children surviving cancer — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "I want to grow hair, I want to grow up, I want to go to Boise : children surviving cancer" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

IF I AM THE MOTHER OF THIS BOOK,

THEN ANN WHEAT IS ITS MIDWIFE...

AND THESE ARE ITS CHILDREN.

Introduction

Whenever I told someone I was writing a new book, they would break into a smile and ask, "What's it about this time?"

When I said it was a book on children surviving cancer, the expression on their faces changed. Their eyes took on a look of pain. Their smiles disappeared and their lips formed a firm line. They looked at me with a pity usually reserved for a woman who had just lost her bank card. When I explained that it would reflect humor and optimism, the look changed againthis time to one usually reserved for a woman who had just lost her mind.

Cancer and optimism were not considered compatible on this planet.

It occurred to me that this is what the children in this book see every time someone looks at them. At the moment they stop being a kid and turn into a child with cancer, the smiles disappear. Every face around them reflects a mixture of sadness, shock, pity orworsereverence for someone chosen to suffer.

Okay, to be honest, I had some misgivings myself at first when Ann Wheat, a young, energetic camp director from Camp Sunrise in Arizona, invited me to lunch to discuss a "project." "Kids with cancer need a little booklet or a pamphletsomething to give them a shot of optimism," she said. "Not every kid who has cancer dies, and they need to know that. They are isolated by the disease and its treatment. You cannot imagine how important it is for them to hear the voices of classmates, siblings, grandparents, doctors, counselors, teachers, friends, and parents who share their nightmare.

"You can do something upbeat," she pressed. "I know you can. Why, I'll bet you didn't know that teens have a contest to see who can wait the longest to throw up during chemo."

Be still, my beating heart! Was this the humor on which I was to feed? Without speaking, I summoned the waitress for the check!

Ann fired her final shot. "Look, there are anywhere from forty to ninety percent of kids out there with cancer who are surviving it. They deserve to be counted and they deserve a chance to live their lives as normally as is possible."

She was right. I could gather a few statistics, talk to some people, and pull together a little booklet in a matter of months.

On a Wednesday morning in July 1987, I flew to Camp Sunrise, just outside of Payson, Arizona, to get acquainted with my material. It was your basic camp with musty tents and mosquitoes that should have been required to file flight plans.

The ultimate goals of these campers were not unlike the ultimate goals of campers everywhere: (1) to use food for the purpose for which it was meant to be usedfights; (2) to go home with the coveted Dry Soap award; and (3) to sock it to the staff. The last is deftly accomplished through a sixty-piece kazoo band at midnight, hanging a nurse's bicycle from the diving board, and planting things in the counselors' beds that crawl in the night causing them to hyperventilate.

But the differences in this camp were not exactly subtle. Artificial limbs and a wheelchair were stored in the corner of the lodge. Several of the campers were bald. A counselor with one leg told me how she visited a border town in Mexico that had had a rash of car-stripping incidents. So she took off her prosthesis and propped it up with the foot showing above the window ledge of the van so someone would think the car was occupied. Not your basic crime fighter, but it worked.

But there was another ritual that pointed out how unique these campers are. It happened around three in the afternoon when little kids with holes in the knees of their jeans and sagging socks climbed down from the trees, came down paths from their hikes, and abandoned their places on bases of the ball diamond. They headed for a small room with a handmade sign that read "MED SHED."

Sandra Priebe, who describes herself as a "gofer" at Camp Sunrise, had observed the ritual for several summers. "No one has to call them," she said. "They know. It's med time. They push open the door and leave their childhood behind them.

"As Sean takes his seat at the card table, his eyes lose the impishness and flash with the alertness that one would expect in an eagle. His ten-year-old size conflicts with his technical expertise. He has the ability to scan blood reports with the same rapid comprehension that his peers might scan comic books.

"When his plastic tray is presented to him, he explains to the nurse the procedure while she listens intently. Each tray is a parent's hope; a child's future. The lines are flushed, and proper swabbing is complete. He leaves the shed to resume his civilian job of dirt wallower, teaser of girls, and climber of trees."

When the late afternoon rains came, I joined a group of ten teenagers jammed in a small, parked RV that normally would have accommodated a little retired couple seeing America first. It was the hour set aside at camp to explore and share feelings.

I edged my way past a pretty nineteen-year-old girl perched on a counter with half of her body in the sink. A boy was sprawled out on the bed staring at the ceiling. The rest of us found seats around the small table. Mercifully, someone cracked a window.

As they talked, I saw and heard their uniqueness. Here was a group of children who had been poked at, x-rayed, smothered with love, ridiculed, punctured, spoiled, abandoned by friends, pitied, counseled, experimented with, lied to, protected, resented, and stared at. They had rarely been listened to.

They were children who had been robbed of their innocence and their childhood, neither of which they would ever recapture again.

They were children who had been sentenced to a period of uncertainty and pain usually inflicted on the elderly who had lived rich, long lives. They were little people whom destiny had tapped on the shoulder and announced, "We interrupt this life to bring you a message of horror."

I expected to hear anger about the disease that brought all of them to this airless trailer on a July afternoon. I didn't hear it.

I expected despair over the hand of cards they had been dealt. That didn't happen either.

I expected fear of a future that held no warrantiesno guarantees. It never came up.

What they did talk about were the people who don't appreciate each day. One eighteen-year-old talked about his friends on drugs. He told them, "You wanna do drugs? Do chemo for a year. It'll give you the same effect and make you feel just as lousy."

They talked about how wonderful it would be if people would let them get on with their lives. "We need hate once in awhile," said one. "I had a teacher last year who shouted at me on the first day of school, 'Sit down and be quiet!' She treated me like everyone else. I knew it was going to be a good year."

"Yeah," said a sixteen-year-old boy. "It's like people whisper around you and they never laugh. Man, without a sense of humor I wouldn't have made it this far."

As they talked and laughed about their lives, suddenly I felt like I was the innocent child and they were the adults, dispensing wisdom. And I knew then these kids deserved better than buckets of tears and public pity. Their legacy was too important to pack away like a fading photograph. In a world short on role models, they set standards that can never be topped.

They tested drugs and served as experimental pincushions in the war to eradicate one of the most devastating diseases of this century. Without them, this book on cancer survival could never have been considered.

The survival rates tabulated in 1989 by St. Jude Children's Research Hospital in Memphis could serve as a national monument to their courage.

Next pageFont size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «I want to grow hair, I want to grow up, I want to go to Boise : children surviving cancer»

Look at similar books to I want to grow hair, I want to grow up, I want to go to Boise : children surviving cancer. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book I want to grow hair, I want to grow up, I want to go to Boise : children surviving cancer and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.