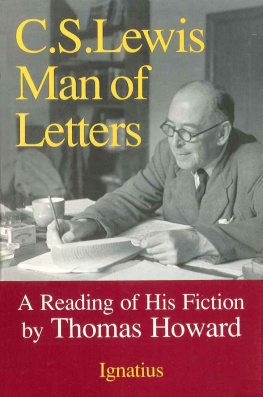

C. S. LEWIS MAN OF LETTERS

C. S. Lewis

Man of Letters

A Reading of His Fiction

by

Thomas Howard

IGNATIUS PRESS SAN FRANCISCO

Previous edition published by

Churchman Publishing

Worthing, England

1987 Thomas Howard

All rights reserved

Cover design by Roxanne Mei Lum

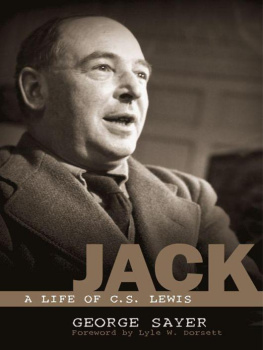

Cover photograph:

C. S. Lewis in his study at the Kilns

1960

Marion E. Wade Center

Wheaton College, Wheaton, Illinois

ISBN 978-0-89870-305-4(PB)

ISBN 978-1-68149-065-6 (E)

Library of Congress catalogue number 90-81993

Printed in the United States of America

To Mrs. Kilby

For you, dear & noble Lady,

because you

like Mother Dimble & Mrs. Beaver

& Lucy & Tinidril

exhibit to us all,

every day, all day,

what goodness (that is to say, glory)

looks like

CONTENTS

by

Peter J. Kreeft

CHAPTER ONE

The Peal

of a

Thousand Bells

CHAPTER TWO

Narnia:

The Forgotten

Country

CHAPTER THREE

Out of the

Silent Planet :

The Discarded Image

CHAPTER FOUR

Perelandra :

The Paradoxes

of Joy

CHAPTER FIVE

That Hideous Strength :

The Miserific

Vision

CHAPTER SIX

Till We Have Faces :

The Uttermost

Farthing

PREFACE

At last! A book about C. S. Lewis that doesnt sound like a term paper, a book that is a joy to read, a book written with Lewis own passionate power with words, Mercurial magic. At last a book that shows us things we didnt see or appreciate in Lewis before, instead of trotting out a recital of the obvious things we did see (unless we were morons).

At last a book that looks along Lewis rather than merely at him; a book that looks at something far more important than Lewis: his world, which is also our world because it is the real world.

So far the plethora of Lewisiana has illustrated two maxims: that inflation cheapens value and that the more interesting the author, the duller the books about him. To see the first maxim, all you need do is live in America. During inflation, the value of gold soars. We are living through a Lewis inflation, and here is some gold.

For the second maxim, first read Homer, Plato, Saint Augustine, or Kierkegaard, then read any commentary you can find about them. Better yet, first read the most exciting book in the world (The Bible, of course), then read a few dozen of the thousands of astonishingly dull books about it.

Lewis is a magnificent writer, strong and soaring. But with only a few exceptions, books about him have been leaden-footed and platitudinous. Here is the most notable exception so far.

What makes it exceptional is that it accomplishes the two things a good book should aim at, according to the sane, sunny common sense of pre-modern, pre-publish-or-perish literary criticism: to please and instruct. That is to say, it offers the human spirit its two most essential foods: joy and truth. Lewis does this; thats why he moves us so, and why most books about him dont. Throw them away and read Lewis again. Why eat hamburger when you can eat steak? Why read by reflected moonlight when you can read by direct sunlight? Why look at a photograph when you can look at the real thing?

Why read this book then? Doesnt any book about Lewis merely shed snow on his bell? The shape may be faithful to the bell, but the snow blurs it a bit; and the sound may be the bells sound, but the snow muffles it a bit. Why not blow away this new snow and hear the naked bell ring out again?

Because this book is not just more snow on the bell. It is an echo chamber, a corridor through which those reverberating bell tones can reach into silent, empty rooms and tombs. It is a witness preaching the ancient and universal gospel of a glory-filled universe to mousey Modern Man, opening a window onto a world that is not modernitys dungeon but the Great Dance; not Playboys playpen but Providences play, the Cosmic Drama; not the formulas of flatness but the fountain, the hierarchy, the Great Chain of Being, packed with peril and drenched in joy. This world is like Aslan: its not tame, but its good.

Tom Howard takes the delightful trouble to make this worldview, which is implicit in all Lewis fiction, explicit in this book. Because he believes, together with the democracy of the dead, together with all pre-modern, pre-secular civilizations, that it is the true world; that nothing is more important than living in the true world; and that one of the most effective ways to waken us out of our little dream worlds into the enormous, terrifying and wonderful real world is through the imagination of a master story teller. And who could do this better than the author of Chance or the Dance ?

I would no more put snow on Howards bell than he on Lewis. My prophetic burden is: look with Tom Howard (not at him) as he tells you to look with Lewis (not at him), and Lewis tells you to look with the world, along the world (not at it). If you do, you will see the ancient stars shining through the modern smog. We are lost in a haunted wood; why should we always be staring at the ground? Lift up your eyes, Jerusalem, and see the weight of glory.

What an unfashionable task for a book today. Hopelessly naive, of course. Simple-minded, wish-fulfillments, desperate dreams. Science has conclusively demonstrated that... modern scholarship is unanimous that... the consensus of the most enlightened opinion assures us that...

Oh, shut up, Screwtape! Go on, reader, I dare you. Take another look.

Peter J. Kreeft

CHAPTER ONE

The Peal of a Thousand Bells

In the early days of World War II, an odd book appeared in England and America. It seemed to be a collection of letters from an old devil to a younger one, telling him how to handle a man who had been assigned to him as his special demonic responsibility.

The book was odd for a number of reasons. For a start, one does not run across infernal letters every day. But then this was not a book on the occult, nor demonism, nor satanism, nor any other sort of arcana. Moreover, it was odd in that, in the darkest days that the West had known for many a century, it caught the attention of Christendom, not by commenting on the dread and apocalyptic political situation we found ourselves in just then, but rather on a much older, more widespread, and infinitely more alarming situation that the race has lived with for aeons. And again, it was odd in that, right in the middle of the twentieth century, after decades of assiduous effort on the part of the modern Church in the West to de-supernaturalize the ancient Faith under the gun of German romanticism, higher criticism, Darwinism, Freudianism, and so forth (this effort was called modernism)just when this effort had swept all before it in Protestantism at leastthere appeared this book which assumed, blithely and unapologetically, that the Devil is real, for heavens sake. Here was Christian theology, anxiously plucking at the coattails of the Western world, assuring everyone that we dont for a moment insist that anyone believe in any nonsense about miracles and God-in-the-flesh, and parthenogenesis and so forth, much less Satan , and along comes a book, not by a white-sock stump-preacher from the boondocks, but by a vastly civilized and luminously intelligent don who obviously believed this awkward stuff.

The book, of course, was The Screwtape Letters , and the don was Clive Staples Lewis.

Who was he? Well, he was a Christian, for a start, of the Anglican variety. But no group in Christendom can claim him as their special spokesman. He was most emphatically a mere Christian, meaning by that, not a watered-down Christian, but a Christian who saw himself as standing in the mainstream of traditional orthodoxy, as that has been taught and held universally for two thousand years ( quod ubique, quod semper, quod ab omnibus creditum est what has everywhere, always, and by everyone been believed: the old Vincentian Canon would apply to him quite well). He took the Bible seriously, but the evangelicals couldnt claim him; and he was unselfconsciously a sacramentalist, but the Anglo-Catholics couldnt claim him. He was Anglican, but Methodists and Roman Catholics and Baptists read him and applauded. He saw as his particular apostolate the task of speaking as plainly as he knew how, in as many ways as he knew how, of the Gospel.

Next page