DAVID A. TALBOT, EMPEROR HAILE SELASSIE MOVES AHEAD

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

THERE ARE INNUMERABLE people who supported me throughout the writing of this book. To my colleagues at Johns Hopkins University and at the University of MassachusettsBoston, I owe immense thanks, especially Christopher Nealon, Jeanne-Marie Jackson, Eric Sundquist, Douglas Mao, Jared Hickman, Hollis Robbins, Lester Spence, Katrina McDonald, Jessica Marie Johnson, Sari Edelstein, Holly Jackson, Eve Sorum, Cheryl Nixon, Matt Brown, Betsy Klimasmith, Cecily Parks, and Aaron Lecklider. I have been overwhelmingly lucky to find myself included in such generous communities, surrounded by such brilliant minds. I have been lucky, too, to have the opportunity to discuss ideas with exceptional students at both institutions.

I thank the Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library at Yale University for the award of an A. Bartlett Giamatti Fellowship to conduct research there, which was responsible for generating a good deal of the work presented here. I am grateful, too, to the receptive audience who attended the talk I gave during my tenure there. Of course, much of this book has been presented at conferences and symposia over the course of the last decade, and it has improved as a result of feedback from those audiences. A landmark conference in Addis Ababa sponsored by Callaloo in 2010 introduced me to GerShun Avilez, Salamishah Tillet, Dagmawi Woubshet, and others whose comments gave clarity to this project in its infancy. Thank you to Joseph Rezek, Theo Davis, and Harvards Mahindra Seminar in American Literature and Culture; the probing questions and comments I received from this audience on a chapter draftparticularly from Sandy Alexandre in her role as respondentwere instrumental in shaping the project as a whole. In addition, I have benefited enormously from both formal and informal discussions at conferences, over email, over coffee, and elsewhere with Susanna Ashton, Russ Castronovo, Ed Folsom, Susan Gilman, John Gruesser, Daniel Hack, Jeannette Jones, Adam McKible, Cherene Sherrard-Johnson, and Lisa Siraganian. Conversations with Christian Crouch, Jean-Christophe Cloutier, and Karl Jacoby were especially generative.

I am enormously indebted to the curators and librarians at the various libraries, museums, and archives where I conducted research for this book. Thank you to Nancy Kuhl, Elizabeth Frengel, and the rest of the staff at the Beinecke Library and at Manuscripts and Archives at Yale University; Skyla S. Hearn at the DuSable Museum of African American History; Peter Harrington and Holly Snyder at the John Hay Library at Brown University; and the librarians at the Houghton Library at Harvard University, Syracuse University Library, and the New York Public Library. Thank you to the wonderful librarians at Johns Hopkins University, especially Gabrielle Dean, Donald Juedes, and Heidi Herr, and the staff of the interlibrary loan office. I am also grateful for the help I received from Lael J. Ensor-Bennett and Ann Woodward, curators of the Visual Resources Collection at Johns Hopkins University, regarding the books many illustrations.

At Princeton University Press, Anne Savarese and Thalia Leaf have been an absolute joy to work with, and I am glad for the opportunity to thank them here for ushering this book into the world, as well as to thank the anonymous reviewers selected by the press for their invaluable feedback. I thank also Brian Halley at the University of Massachusetts Press, who offered to talk with me about my project early in the writing process, which was a tremendous help.

An earlier version of was published as an essay in A Companion to the Harlem Renaissance, edited by Cherene Sherrard-Johnson (New York: Wiley-Blackwell, 2015), 42339. I thank Johns Hopkins University Press and Wiley-Blackwell, respectively, for allowing the reprinting of those pieces here. Thank you to the Morgan Library and Museum, the Beinecke Library and the Manuscripts and Archives Division at Yale University, and the British Museum for permission to reproduce the images included in this book.

While engaged in a project that resonates with me so intimately, it is unsurprising that talking with those closest to me has yielded some of the critical insights that have contributed most greatly to my thinking. Thank you to my sister Siham and my brother Safy, whom I appreciate more than I can say. My extended family, too, has been wonderfully supportive throughout the writing of not only this book but the previous one, the publishing of which prompted my New Jersey aunts and unclesGetachew, Shewaye, Kadra, and Elhamto close the family restaurant for a night in order to throw me an incredible party. I am grateful always for the intellectual and emotional support provided by the brilliant Asali Solomon, going back to our childhood days at the University of California at Berkeley, and by her equally brilliant husband, Andrew Friedman. Nicholas Nace has read numerous drafts of numerous parts of this book, and I could not have written this book without his help. Thank you to Dr. Bereket Selassie, who has, since my childhood, been a stunning model of scholarship. My father, fellow writer, to whom this book is dedicated and without whose love and encouragement I could not have written it, has been my greatest champion throughout my life. Who else would have bought me a cake depicting the cover of my first book for the aforementioned New Jersey party? I write for him and for the memory of my mother.

Finally, my immeasurable love and gratitude go to Chris Witt, my awesome partner in life and my tireless supporter in all things, including this.

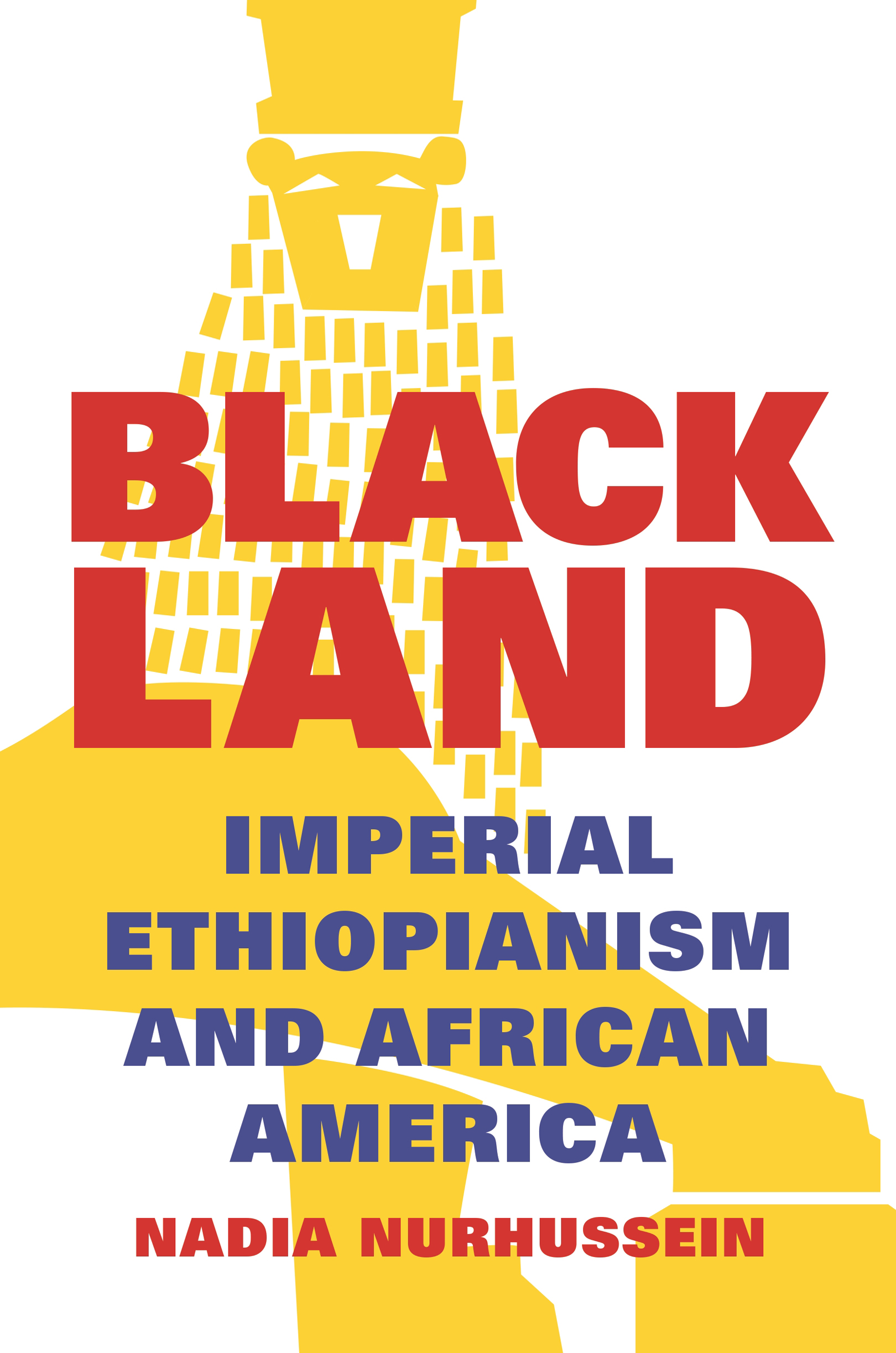

BLACK LAND

Introduction

Princes shall come out of Egypt; Ethiopia shall soon stretch out her hands unto God.

PSALMS 68:31, KING JAMES BIBLE

THREE YEARS AFTER the bloody Chicago Race Riot of 1919, during which postwar racial tensions erupted into violence that resulted in dozens of deaths and hundreds of injuries, the Chicago Commission on Race Relations published The Negro in Chicago: A Study of Race Relations and a Race Riot. In a chapter section called The Abyssinian Affair, the commission recounted the story of the Star Order of Ethiopia, a small group of Negroes styling themselves Abyssinians who, on 20 June 1920, publicly and ceremonially burned two American flags. According to the Chicago Commission, the flag burning intended to symbolize the feeling of the Abyssinian followers that it was time to forswear allegiance to the American government and consider themselves under allegiance to the Abyssinian government. The debacle resulted in the shooting and injuring of several people and the killing of two.