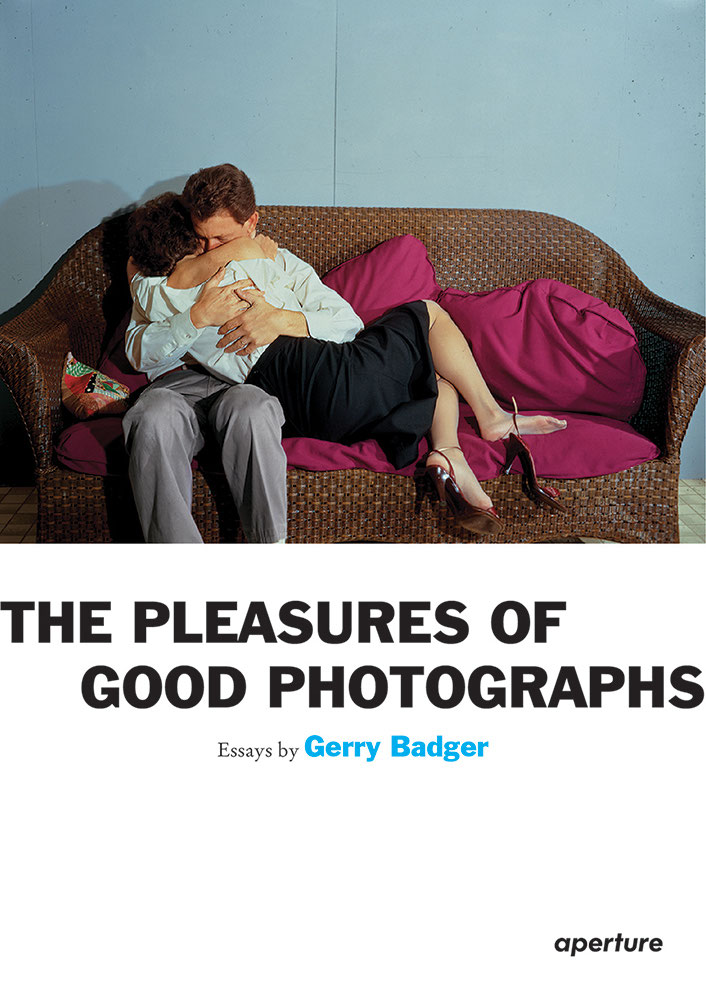

THE PLEASURES OF GOOD PHOTOGRAPHS

Essays by Gerry Badger

Plate

John Gossage, First Day with the Leica, Washington, 2007

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

The Pleasures of Good Photographs

Literate, Authoritative, Transcendent: Walker Evanss American Photographs

Simply the Best: John Szarkowski and Eugne Atget

A Tale of Two Portraits: La Comtesse de Castiglione and Blind Woman

The Other Richard Avedons Nothing Personal

Ruthless Courtesies: The Making of Martin Parr

A Certain Sensibility: John Gossage, the Photographer as Auteur

Pleasant Sundays: Robert Adamss Listening to the River

INTERLUDE: THE WALK TO PARADISE GARDEN

From Here to Eternity: The Expeditionary Artworks of Thomas Joshua Cooper

Invisible City: The L.A. Street Photographs of Anthony Hernandez

Far from New York City: The Grapevine Work of Susan Lipper

Country Matters: Anna Foxs Photographs 19832007

Odysseys: Patrick Zachmann and Contemporary Diaspora

From Diane Arbus to Cindy Sherman: An Exhibition Proposal

Without Author or Art: The Quiet Photograph

Elliptical Narratives: Some Thoughts on the Photobook

Its Art, But Is It Photography? Some Thoughts on Photoshop

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

REPRODUCTION CREDITS

INTRODUCTION

Leaving aside the mysteries and inequities of human talent, brains, taste and reputations, the matter of art in photography may come down to this; it is the defining of observation full and felt.Walker

It is just over thirty years since I wrote my first essay on the subject of photography, and over forty since I first became hopelessly beguiled by the medium. I began my writing career with a piece on the work of Wynn Bullock for the Royal Photographic Society The great West Coast photographer was having an exhibition at the then RPS headquarters in South Audley Street in Londons Mayfair, and I was volunteered to write the piece because I said I knew something about his work and was enthusiastic about it. I was most gratified to receive a fulsome letter from Bullock about the articlea letter I still treasure. I learned soon afterward from his daughter, Barbara, that the letter had cost him much effort, as he was in the last stages of his final illness. Indeed, a note from Barbara informing me of his death arrived soon after the first missive.

Wynn Bullocks kind letter encouraged me greatly, and reviews of exhibitions by Manuel lvarez Bravo and Lee soon followed. In addition to taking my own photographs and pursuing a busy career in architecture, I have been writing about photography ever since.

So in a way, I rather stumbled into photo-criticism, but looking back at some of those first pieces, I realize that I was writing not so much to explain the work of these photographers to an audience, but to understand it for myself. And that, I hope, has been my guiding principle ever since. Rather than talk to the reader in the manner of a teacherwhich often means talking downI try to construct a personal meditation on a photographers work, as if thinking aloud about it. I dislike hectoring criticism, and although I have strong opinions, I hope I leave room for other points of view in my writing.

I was fortunate also to begin by writing about the work of three great photographers. The richer and more complex the work, the more nourishment for the critic to feed upon.

My introduction to the medium in the early 1960s came at a time when John Szarkowski was leading the fight for photography to be recognized as a fully fledged art form. Szarkowski was the champion of classic modernist photography in the documentary mode, and this wasand still ismy basic approach. Yet when I began writing about photography in the mid-1970s different critical attitudes, often vehemently opposed to the Szarkowski position, were gaining ground. I fully admit that I was somewhat slow in taking to some of these ideas, particularly those of the French structuralists, and I still have grave doubts about the wilder shores of academic theory. Certain checks were necessary, I suppose, to counter the iniquities of reductive formalism, yet the pendulum on occasion undoubtedly swung too far. I still fundamentally believedespite what many might say to the contrary in the furtherance of their careersthat most photographers make photographs not to illustrate theories but to make pictures. As I have said elsewhere, many things might move a photographer, but not always to take a photograph.

I suppose that I stand somewhere in the middle of the battle between the formalist and contextual schools of criticism. I still firmly believeif not in geniusat least in talent. In my opinion, anyone who doesnt just isnt looking. But when I began in photography, my primary interest was in the fight for its recognition as art. Now, I am not sure if I care whether photography is art or not. Too often, those looking to make photographic art deny its basic documentary faculty. For me, the documentary, or the documentary mode, remains not only the core of the medium, but the source of its greatest potency. Those making hybrid work, or photography about photography rather than the world, have to fight harder for my attention than those documenting modern life.

My feelings about the medium will emerge in greater detail during the course of these essays, which, with two exceptions, have been written for this book, although I have incorporated some material here and there from previously published This book could be looked upon as something of a survey of my past interests, so familiar names crop up, along with favorite quotes.

As far as writing about photography is concerned, for me the master was Szarkowski. He could be a little narrow in his perspective at times, but he was second to none as a stylist and was supreme in his insights. His great virtue was that he himself was a photographer, so he knew from experience the kinds of thoughts that went through a photographers mind at the crucial moment of clicking the shutter.

Szarkowski, I suspect, learned a thing or two about photographic writing from Walker Evans, who might have been the best writer ever on the medium if he had written more. I dont know how much Evans learned from Lincoln Kirstein, but for me the finest single piece on the medium was written by Kirstein as the afterword to Evanss own great 1938 photobook, American In that essay, Kirstein sketched a vision of photographic modernism that was much broader than simple formalism. It was an austere, yet grand vision, one that I feel remains as relevant today as on the day it was written. I frequently return to Kirsteins wise words when I am faced with, and am depressed by, some of the atrocities one sees at photo fairs and in the galleries.

American Photographs of course is one of the seminal photobooks. It certainly has been the biggest single influence on my photographic career. I have become particularly associated with the photobookto my great delightfor it is in the photobook, in my opinion, where photography sings its loudest, most complex, and satisfying song. Many of these essays, while about a photographers work, are about one or more of their books.

But these are interesting times for both the photobook and the medium. Photographys value as art has never been so high, yet in these mediawise and Photoshopping times its value as documentary has never been so questioned. The photobook is enjoying an unprecedented boom, although this phenomenon may simply reflect its last hurrah before the book as a physical object more or less disappears. Yet, excitingly, on the computer screen that may see it into history, photographers will be able to combine photographic images with text, sound, and segments of movie film. I like to think that the book will survive, but this may be only wishful thinking. At a symposium on the photobook in November 2006, I and the other speakersall of a certain agewere optimistically expressing the view that the tactile qualities of the book would always be cherished, and who would want to stare at a computer screen, and so on and so forth. Then some kid from the audience, in his late teens or early twenties at the most, expressed the scornful view that we were all talking horseshit, or words to that effect, and he may well have been right.