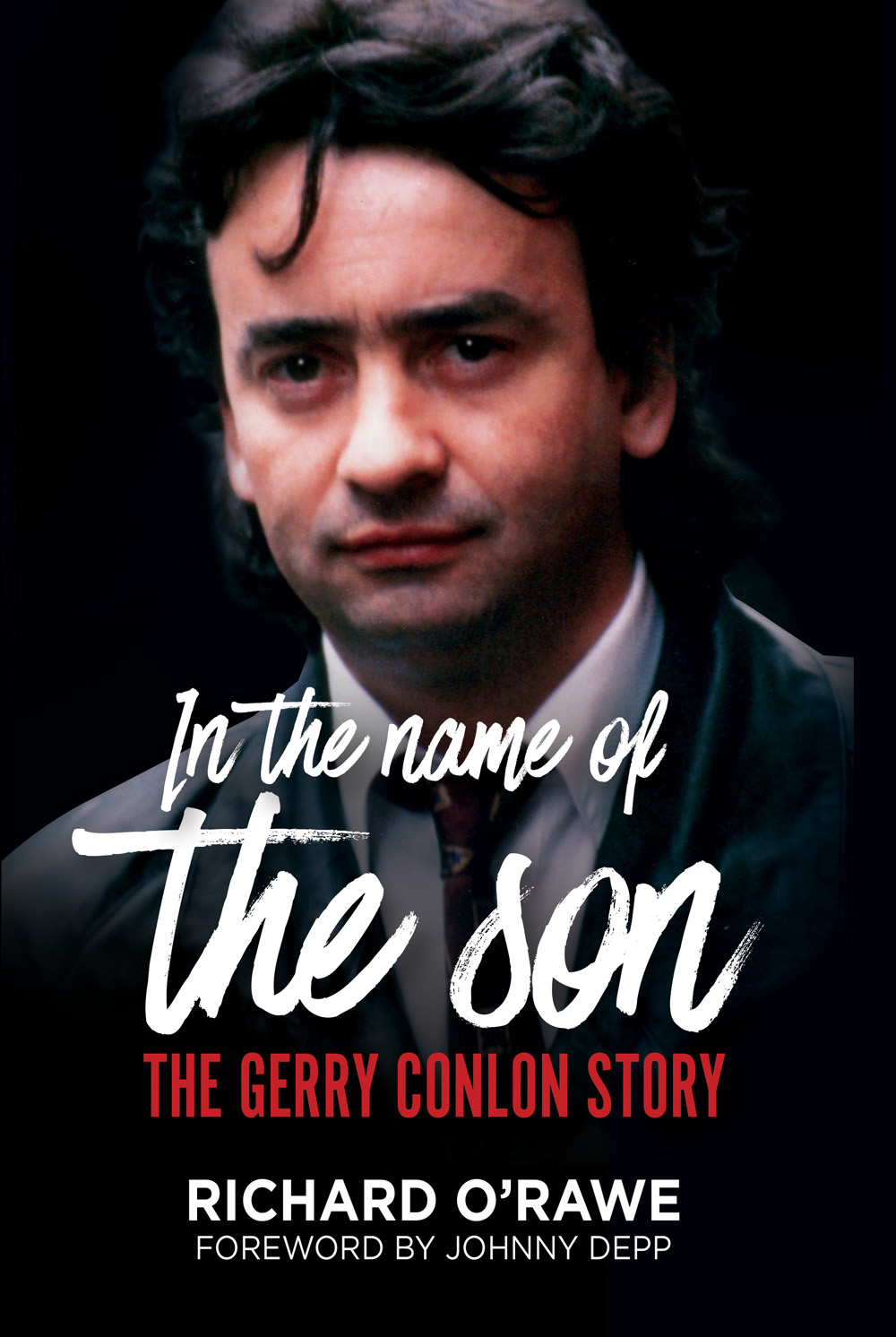

ADVANCE PRAISE FOR IN THE NAME OF THE SON

As fond as ORawe is of Gerry Conlon, this is not a hagiography. Conlon is shown in all his imperfect splendor, his contradictions and complexities, as both a victim of the conflict in Northern Ireland and ultimately a survivor whose inherent humanity and decency rise above ancient animosities and modern human failings. Written by someone who emerged from the same cauldron that swallowed so many of their generation, ORawes unsparingly honest account does many things, none more so than make us fervently wish that Gerry Conlon lived much longer, because he had so much more to teach us.

Kevin Cullen, columnist and former Ireland correspondent for The Boston Globe

A vivid, bracing, often funny account of the wild and tragic but ultimately inspiring life of Gerry Conlon. With great affection and compassion for his subject, Ricky ORawe has written a biography that captures Conlons self-destructive demons, but also his infectious lust for life.

Patrick Keefe, The New Yorker

Rick ORawe has written a searingly honest, deeply moving and all encompassing account of the life of Gerry Conlon. Gerrys lust for life was only matched by his unquenchable thirst for justice not just for the Guildford 4 but for all those who have fallen foul of an often corrupt and politically loaded judicial system. The author deserves praise for refusing to allow his lifelong, deep friendship with Conlon to whitewash many of Gerrys own personal failings. Yet in the end ORawe still does justice himself to the memory of a remarkable, courageous and lovable character.

Henry McDonald, The Guardian

Gerry Conlons remarkable life deserves the honest integrity ORawe brings to his task. It is a labour of love but without being a hagiography of his friend [and] contributes to the ongoing quest for truth how the State got it so wrong and why no one has been brought to justice for the Guildford Pub Bombings These are questions Gerry Conlon fought to have answered and which ORawe lays out with forensic detail.

Kevin R. Winters, international human rights lawyer

Richard ORawe and Gerry Conlon grew up together in Belfasts Lower Falls area they were life-long best friends and confidantes. ORawe is a former Irish republican prisoner and was a leading figure in the 1981 Hunger Strike in the H Blocks of the Maze prison. He is the author of the best-selling book Blanketmen: An Untold Story of the H-Block Hunger Strike (2005) and Afterlives: The Hunger Strike and the Secret Offer that Changed Irish History (2010).

In the name of

the son

In the name of

the son

THE GERRY CONLON STORY

RICHARD ORAWE

First published in 2017 by

Merrion Press

10 Georges Street

Newbridge

Co. Kildare

Ireland

www.merrionpress.ie

Richard ORawe, 2017

9781785371387 (Paper)

9781785371394 (Kindle)

9781785371400 (Epub)

9781785371417 (PDF)

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

An entry can be found on request

Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data

An entry can be found on request

All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved

alone, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in or

introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any

means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise)

without the prior written permission of both the copyright owner and the

above publisher of this book.

Interior design by www.jminfotechindia.com

Typeset in 11.5/14.5 Adobe Caslon Pro

Cover design by www.phoenix-graphicdesign.com

Cover front: Gerry Conlon in New York, 1990. Photo courtesy of the Conlon family.

Cover back: Courtesy of Hugh Russell/ The Irish News

Contents

Upon Thinking of My Long-Lost

Brother, Gerry

20.8.17

I first met Gerry Conlon, by absolute chance, in the hallway of a talent agency in Los Angeles, somewhere around 1990, I believe. It was a rare occurrence for me to visit the place, which made the moment with Gerry all the more charmed.

I had pressed the button and was en route to my destination floor. Upon arriving, the doors opened. As I exited, I spooked a couple of guys to my left, who looked, as did I, sorely out of place. The guts of this heinous, monolithic terrarium of steel, glass and dubious art, sparsely shaming those ghastly modern walls, was not a typical setting for folk such as myself, or gents of this breed, who, in my personal and moderately professional estimation, were satisfactorily saturated and teetering along the same invisible ledge, as though theyd been out on the prowl, for an especially impressive stretch. Indeed, they looked just like the depraved, miscreant, unhinged maniacs I always tended to hang out with. One of them possessed the squinty scrutinising eyes of the streets, and was as skinny as a dried lizard. He also seemed to have been divined with a prevailing lack of residents in the tooth department. The questionable few choppers that had not been evicted, were lonely, jagged and rotting. His stringy, straight hair greasy to his shoulders. This was Joey Cashman. A hilariously clever and quick-witted Irishman, from just outside Dublin. He was the manager of one of my favourite humans of all time, the infamously tattered genius of lyric and song, Shane MacGowan, from the Pogues. Joey was a lovely man, who held strong to those he loved. Devoted and solid. I would later survive many adventures with this man, and to this very day, I have been informed of Joeys tragic and sudden demise, and miraculous resurrection, at least fourteen times. The other fella was from heavier stock. He laid a big, beautiful, slightly crazed Cheshire Cat smile on me, which showed that this man had at least met a dentist once in his life. But it was his eyes that got me. Eyes that simultaneously exuded wisdom and a childlike purity; a desire to live and love. There was no question that these powerful eyes had seen and experienced much. This was Gerry Conlon. He approached me and introduced himself and his mate Joey, with the exuberance of a man who held nothing back. He gave of himself freely. His eyes sparkled like ten thousand stars had just given birth to ten thousand more

Gerry Conlon had first gotten my attention when he stomped out of the Old Bailey in London in October 1989, fists raised high and declared to the world that he was an innocent man who had spent fifteen years in jail. The authorities had tried to shove him out the back door, in order to avoid the inevitable media frenzy, but he had refused, instead imparting something along the lines of Fuck you, Im a free man, youse fuckin brought me in the back door, Im going out the front! My curiosity had then been further fired when Id learnt that hed witnessed his father, Giuseppe, another innocent man, die in a British prison. And now here he was, Gerry himself, stood right before me, in this, the most incongruous of places possible. Fortunately, to prevent matters from being overtly one-sided, he recognized me from something or other and lunch was duly arranged.

Gerry was altogether an articulate, personable, funny, self-deprecating and fierce humanitarian. He was an absolute gentleman, who possessed all the knowledge of law in the streets of Belfast. Chivalrous, loyal and highly sensitive to any injustice, no matter how large, or minute. If he loved you, you were blessed to be invited into his circle, where there existed no edits with him. Gerry said what he felt and meant what he said. He had no difficulty in getting his point across. Ever. He had grown so used to having his prison clique around him that those of us who spent significant amounts of time with him became a newfangled version of just that. He was a 100% trusted friend and brother, to the very end.

Next page