Long Kesh concentration camp lies beside the M1 motorway about ten miles from Belfast and near the town of Lisburn; nowadays the British government insists that everyone should call it Her Majestys Prison, The Maze. A rose by any other name

Almost twenty years have passed since Long Kesh was opened, and through the years it has been a constant element in the lives of all the members of my family. On any one of the many days since then, at least one of us has been in there. My father was one of the first to be imprisoned there when he and my Uncle Liam and a couple of my cousins were interned without trial in August 1971 in Belfast Prison and transferred to Long Kesh when it opened to its unwilling guests in the following month. My brother Dominic, who was only six when our father was first interned, has been in the Kesh for the last few years, and this year our Sean endured his first prison Christmas. Our Liam did his time a few years ago, and Paddy A., our eldest brother, has been in and out a few times. Thats all the male members of our clannapart from me, of course, and a handful of brothers-in-law and several more cousins.

Our female family members, like Colette and other wives, sweethearts, sisters, sisters-in-law, aunts and my mother, have spent almost twenty years visiting prisons. Yet for all that, ours is a perfectly normal family, and we are by no means unique. Long Kesh is full of our friends, and the north of Ireland is coming down with families just like ours, all with a similar British penal experience.

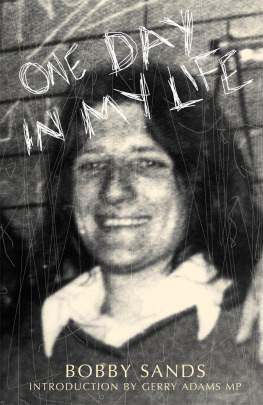

Thousands of men and women have been incarcerated by the British government during this last twenty years. Thousands of wives and mothers and fathers and husbands and children have spent years visiting prisons, and it is they who do the real time. Today there are almost 800 Republican prisoners, most of whom are in British jails in the occupied six counties of Ireland. Others are imprisoned in Britain itself or are in the Dublin governments custody in Portlaoise and other prisons. A handful are in prisons in continental Europe or in the USA. Everyone in the nationalist community in the north of Ireland knows someone who is or has been in prison. None of us is immune.

I was first interned in March 1972 on the Maidstone, a British prison ship anchored in Belfast Lough. It was a stinking, cramped, unhealthy, brutal and oppressive floating sardine tin. We had the pleasure of forcing the British government to close it. A well publicised solid food strike, organised at an opportune time when the government was replacing its old Stormont parliament with an English cabinet minister, ensured the Maidstones demise. We were airlifted to Long Kesh. A few months later I was released from Long Kesh, but thirteen months after that I was airlifted back in again, this time black and blue after being used as a punchbag in Springfield Road British army barracks and spending a few days in Castlereagh interrogation centre.

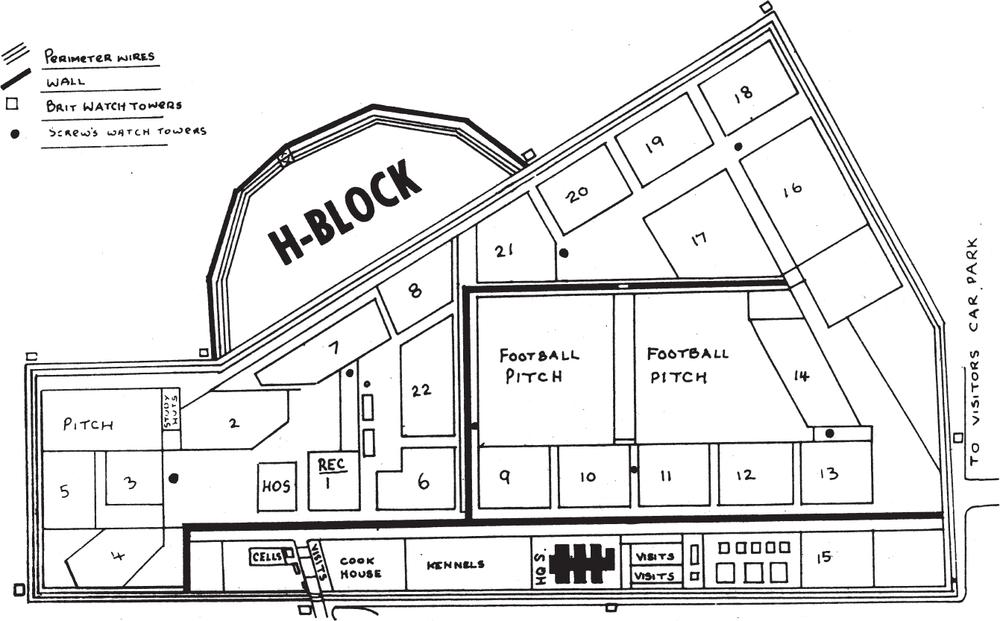

Long Kesh had grown: now over twenty cages contained both internees and Loyalist and Republican sentenced prisoners. In the internment area I became the camps most unsuccessful escapee, but I was consoled by my involvement in the successful elopements of many of my close comrades. I was only caught twice.

In October 1974 we showed our heartfelt appreciation for being interned without trial by joining the sentenced prisoners in burning down the camp; and just as it was being rebuilt my escape attempts caught up with me, and I received two separate sentences of eighteen months and three years respectively. For a while I was an internee, a sentenced prisoner and a remand prisoner, all at the one time. Then I was moved with other would-be escapees to the sentenced area of the camp. From one cage to anotherto Cage Eleven.

Today these cages no longer contain political prisoners, for they are held in Long Keshs infamous H-Blocks and in other jails. Cage Eleven exists now only in the minds of those who were once crowded into its Nissen huts. It is a memory which reminds us, among other things, that the H-Blocks, like the British regime which spawned them, will one day be only a memory also.

The bulk of this book is derived from articles which were smuggled out of the cages and published, under the pen-name Brownie, between August 1975 and February 1977 in Republican News, the Belfast Republican newspaper which has since amalgamated to create An Phoblacht/Republican News. I was one of a small number of Long Kesh POWs who contributed to the weekly column in which we wrote, sometimes none too fluently, about a litany of issues as we perceived them from our barbed wire ivory tower.

Many of the pieces I wrote then and many of the chapters of this book are lighthearted, and the reader may imagine from them that Long Kesh was a happy, funny, enjoyable place. It was not then and it is not today. But the POWs were happy, funny, enjoyable people who made the best of their predicament. We wanted out, but we did our whack as best we could. We did our time on each others backs, and at times we may have got each other down, but mostly we enjoyed one anothers company and comradeship . The lighthearted pieces celebrate that enjoyment.