AS SECOND President of the United States, John Adams in his single term has been overshadowed by both his predecessor and successor. Yet this chubby, opinionated New Englander, stubborn and egotistical, was truly a Founding Father, one of the handful of men without whom it would be impossible to imagine later America. Washington, reserved and aloof, even while President, became a symbol, a presence sufficient to chill the hand of anyone presumptuous enough to slap him on the back. The Father of his Country stood apart from ordinary humanity. Adams was all too obviously human, from his outer appearance to his tactlessly assertive manner, cranky, jealous, yet with a razor-sharp intellect and a keen awareness of his own weaknesses. An English diplomat considered him the most ungracious man he had ever encountered. Benjamin Franklin thought him always an honest man, often a wise one, but sometimes in some things absolutely out of his senses. The three-branched system of American constitutional government with its built-in system of checks and balances owes more to him perhaps than to any other one man. Though he was equally opposed by Jeffersons democratic and Hamiltons aristocratic extremists, he did establish governmental precedents at a time when it was a question whether the American experiment could survive. In later times his views appear more solidly correct than Jeffersons Rousseauistic fancies of the goodness of natural man or Hamiltons feeling of the people as a great beast. The somewhat unprepossessing little man was more intelligent than Washington and far more learned, more rational than Jefferson in regard to human nature, a political figure to whom his country would remain permanently indebted.

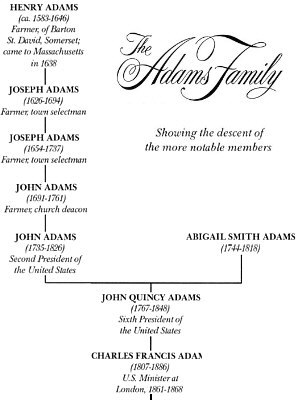

In 1823 in the piety of his old age Adams erected a monument in his native Quincy, Massachusetts, to his first American ancestor, Henry Adams, who in 1638 left old England for the new. In the words of John, Henrys great-great-grandson, this obscure farmer took his flight from the Dragon persecution. The inscription was more a feeling of what ought to be than an established fact, as indeed was the long pedigree produced by the next generation of Adamses to demonstrate their descent from an ancient Gloucestershire baronial family. Later and more professional genealogists would determine that the first American Adams was born in the little village of Barton St. David in Somerset, among the Polden Hills just seven miles southeast of Glastonbury. His father and grandfather had been tenant farmers there before him, not independent yeomen but leaseholders of the lord of the manor, raising sheep and cattle and living in simple thatch-roofed stone cottages.

Henry, the third-generation copyholder and founder of Americas most durable dynasty, remains a dim figure, illuminated only briefly by a few crabbed lines in court and parish records. It is known that he was born about 1583, that his people had lived in Barton St. David for over a century, and that at the age of twenty-six he married the twenty-two-year-old Edith Squire, the daughter of the blacksmith of neighboring Charlton Mackrell. In the next twenty-one years Edith bore her husband nine surviving childreneight boys and a girla surprising total in that day of high infant mortality. No doubt there were other children who did not survive. For some reason the Adamses between 1614 and 1622 moved to the adjoining parish of Kingweston. From there Henry and Edith left England for America. Why they left, what they hoped for, how they felt on turning their backs on the land of their inheritance remains supposition and conjecture. Like most emigrants their motives were uncertain even to themselves, a mixture of piety, shrewdness, ambition, restlessness, resentment, and hope. In the first half of the seventeenth century English migration was part of the time-spirit, an uneasy impulse accentuated by hard times that brought soaring prices in lands and rents and ever more exacting taxes. Between 1620 and 1640 some sixty-five thousand Englishmen sailed away to the West Indies or the American continent.

Henry Adams may have been one of these restless men, unable to own land and eager to go where land was almost for the asking. There is no sign that the dragon persecution had troubled him in his remote village. For the most part the parishoners of Barton St. David seemed unaffected by the lapping waves of dissent. Marriages, baptisms, and funerals took place for the Adamses as they always had, in the accepted tradition, under the curious octagonal tower of St. Davids Church. But in adjoining Dorsetwith Somerset and Devon a stronghold of Puritanismthe Reverend John White of Dorchester, a Puritan moderate remaining within the established Church, had stirred many a yeoman and farmer to consider leaving the timeworn paths of his ancestors. In 1623 White organized the Dorchester Adventurers to aid both non-conformists and loyal churchmen in the settling of New England. Then in 1628 the Adventurers were absorbed by the Massachusetts Bay Company which secured a liberal charter for its colonists. From 1629 to 1640 about twenty-five thousand Englishmen, mostly so-called Puritans, left their homeland for New England. Among the early migrants was Edith Adamss younger sister, Ann, married to Aquila Purchase, a master of Trinity School, Dorchester. The Purchases sailed from England in 1633. Aquila either died on the voyage or shortly afterward. His widow remained in New England, being granted four acres of land in the new Dorchester. In 1637 she married a widower, Thomas Oliver of Boston.

Five years after the Purchases, the Adamses finally sailed. With them were eight of their nine children; their sons Henry, Thomas, Samuel, Peter, John, Joseph, and Edward and their one daughter, Ursula. Their third son, Jonathan, would remain behind for another dozen years. Accompanying them on the voyage was Margaret Shepherd, another of Ediths four sisters, with her husband, John.

As the head of a family of ten and on payment of three shillings an acre, Henry was granted forty acres at Mount Wollaston, six miles south of Boston, where the genial royalist Thomas Morton a decade before had established his ephemeral Puritan-defying Merry Mount. In 1640 Mount Wollaston became part of Braintree (later Quincy). By the time Henry received his acres the initial land clearing had been made, the first roads laid out, a school set up, and a First Church established. More influential Mount Wollaston settlers like Edmund Quincy and William Hutchinson, the husband of the irritatingly heretical Anne, were granted as much as five hundred acres each by the Massachusetts legislature, the General Court. Henry Adams contented himself with his forty.